Affordance and Play: Chandless Estate

Play and freedom

Many spaces planned for play offer truly little. This is because their designs are often limiting the spirit of play as a part of our human condition. According to Lefaivre (2007), the design of our urban spaces has replaced freedom in discovery by over-emphasizing anxieties about safety. As a result, many areas designed for play only restrict child-like exploration and creativity. Play represents freedom, freedom spaces are spaces to deviate from the norm. Lefaivre describes play, as an activity for all age groups, with immense social and health benefits. Seen in this light, play is an essential part of life. How then do we begin to approach spaces for play? We might find insightful examples by looking at how urban residents are already utilising space.

Adventure Playgrounds

Frost and Henninger (1979) decry traditional playgrounds for not being able to meet the play requirements of children. Reconstructed, Places earmarked for demolition and desolate grounds within cities can provide opportunities for free play (Lefaivre, 2007). These spaces have the potential to bring people of various age-groups together, for instance. Miller (1971) posits that these play areas need to be studied as they have an enormous influence of children’s development. One precedent that I find exciting for exploration are Adventure playgrounds. The first adventure playground was developed in Emdrup as far back as 1943. In Emdrup, the designers successfully encouraged creative potential of children by providing an endlessly flexible space (De Coninck- Smith and Martha Gutman, 2004).

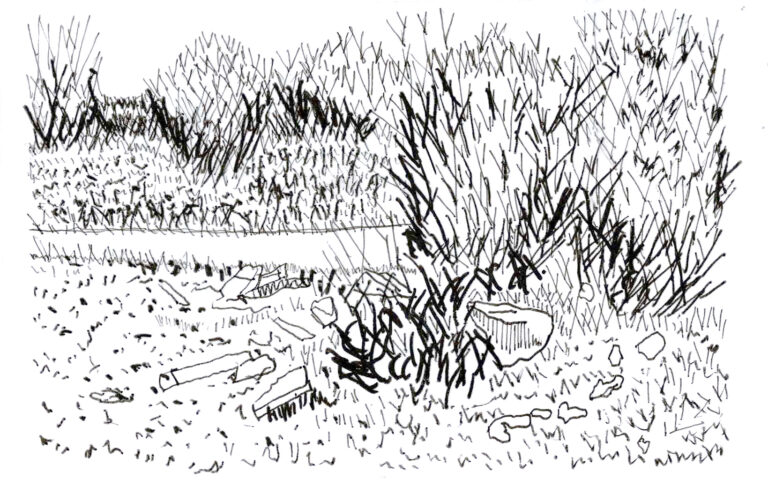

Having considered these, an opportunity arises for the old Chandless estate. The Old Chandless estate has been derelict for many years. If play spaces are spaces to deviate from the norm, then we need to understand the site as one that deviates from the norm. Its proximity to schools across the road means there is already a strong demographic of potential participants. This was indeed my experience when we observed three students already on the site. The site is also littered with the raw materials for play including artifacts of the estate, discarded tyres, old electronics, and goal posts. With a keen eye, one can already see the building blocks for a playground. Therefore, sites such as the Chandless estate would benefit from design that has play, specifically adventure playgrounds, at the forefront.

Bibliography

de Coninck-Smith, N. and Gutman, M., 2004. Children and Youth in Public. Childhood, 11(2), pp.131-141.

Frost, J. L. & Henninger, M. L. (1979). Making playgrounds safe for children and children safe for playgrounds. In R. D. Strom (Ed.), Growing through play. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Lefaivre, L., 2007. Ground-up City play. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

Miller, P. (1971). Creative outdoor play spaces. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.