Ageing communities. Illustration by Luke Leung

Ageing communities present a variety of challenges; social exclusion, inadequate access, and isolation. Thus, new urban spaces must be designed with the resolve of these issues of paramount importance.

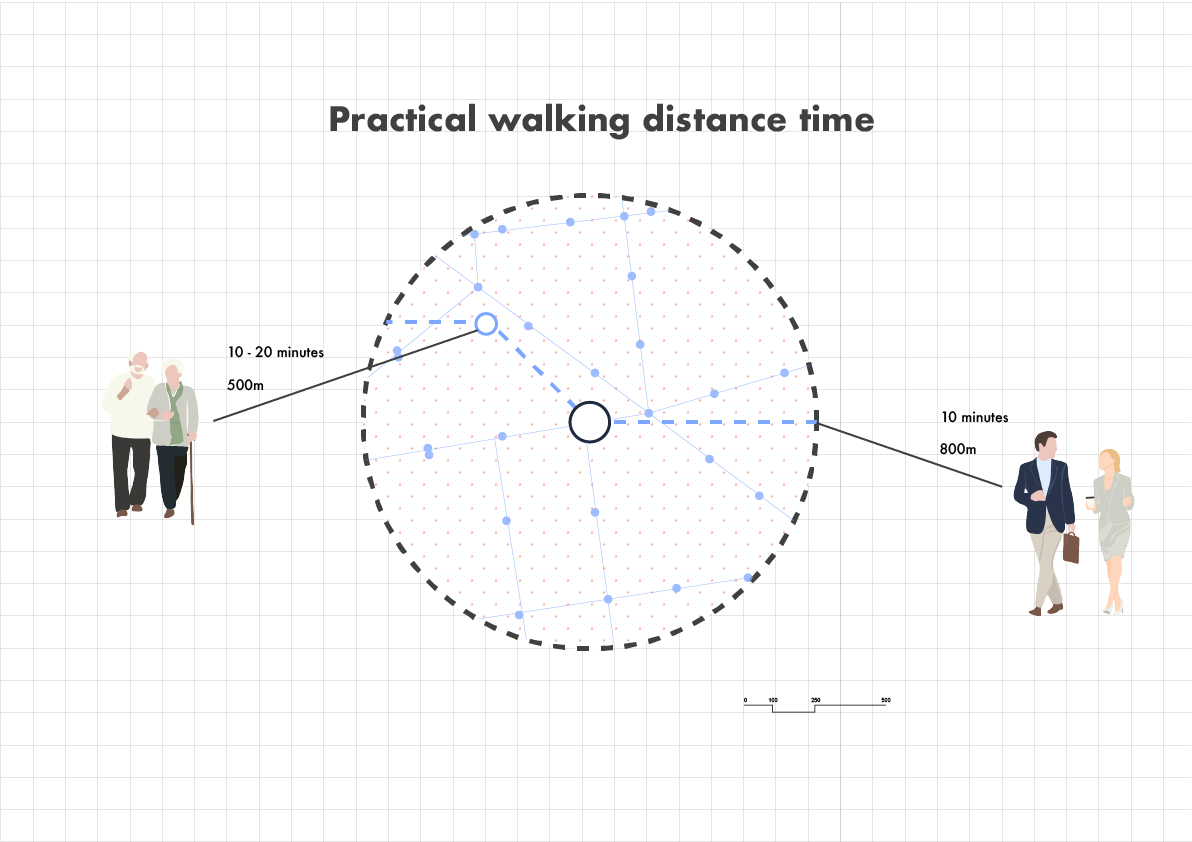

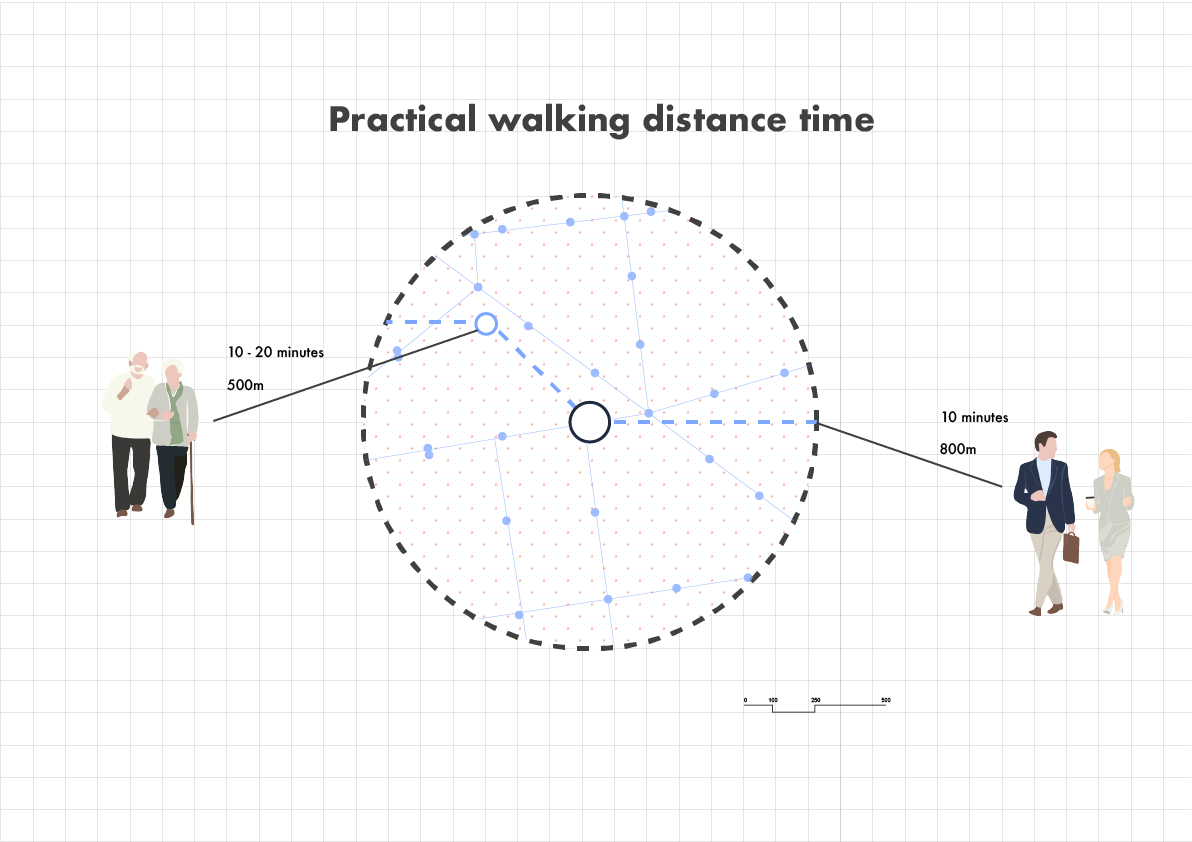

However, how components of the urban realm are planned is typically based on the perspective of the average healthy individual. For instance, the British government claims that 10 minutes is a practical amount of time to walk to infrastructure and amenities, based on the minutes it requires young individuals to commute 800 metres by foot (Burton & Mitchell, 2006). Whereas, the average person aged 70 and above generally needs around 10 to 20 minutes to walk 400 to 500 metres and often cannot walk for more than 10 minutes without resting (ibid, 2006).

Practical walking distance time. Illustration by Luke Leung

Therefore, it is critical to consider the needs and obstacles of diverse audiences when designing cities, neighbourhoods, or even streets. Each detailed element – such as paving materials, dropped kerbs and pleasantness environments – should be considered during the design implementation stage (CIHT, 2015).

Design elements. Illustration by Luke Leung

What are some of the steps to providing age-friendly spaces?

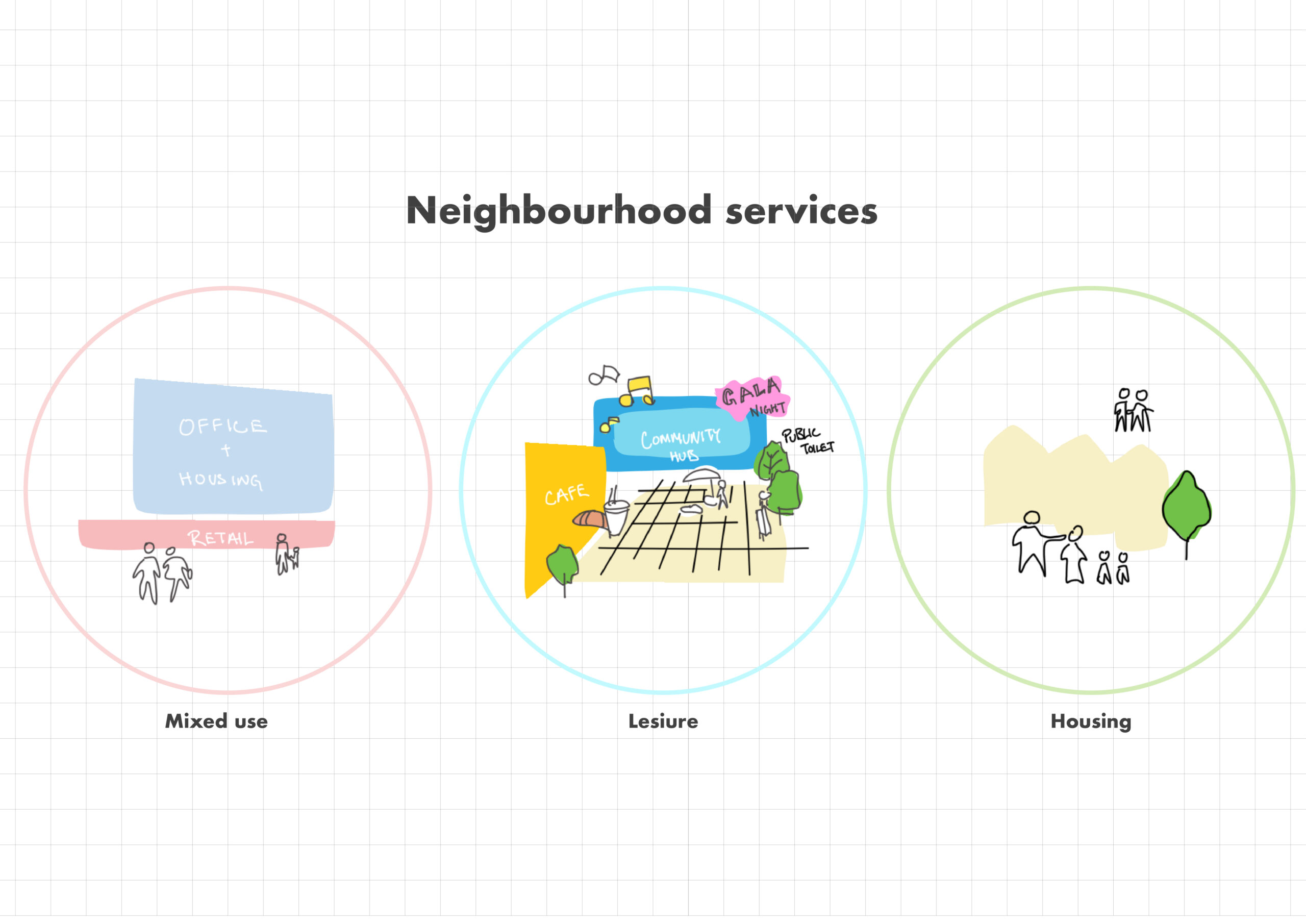

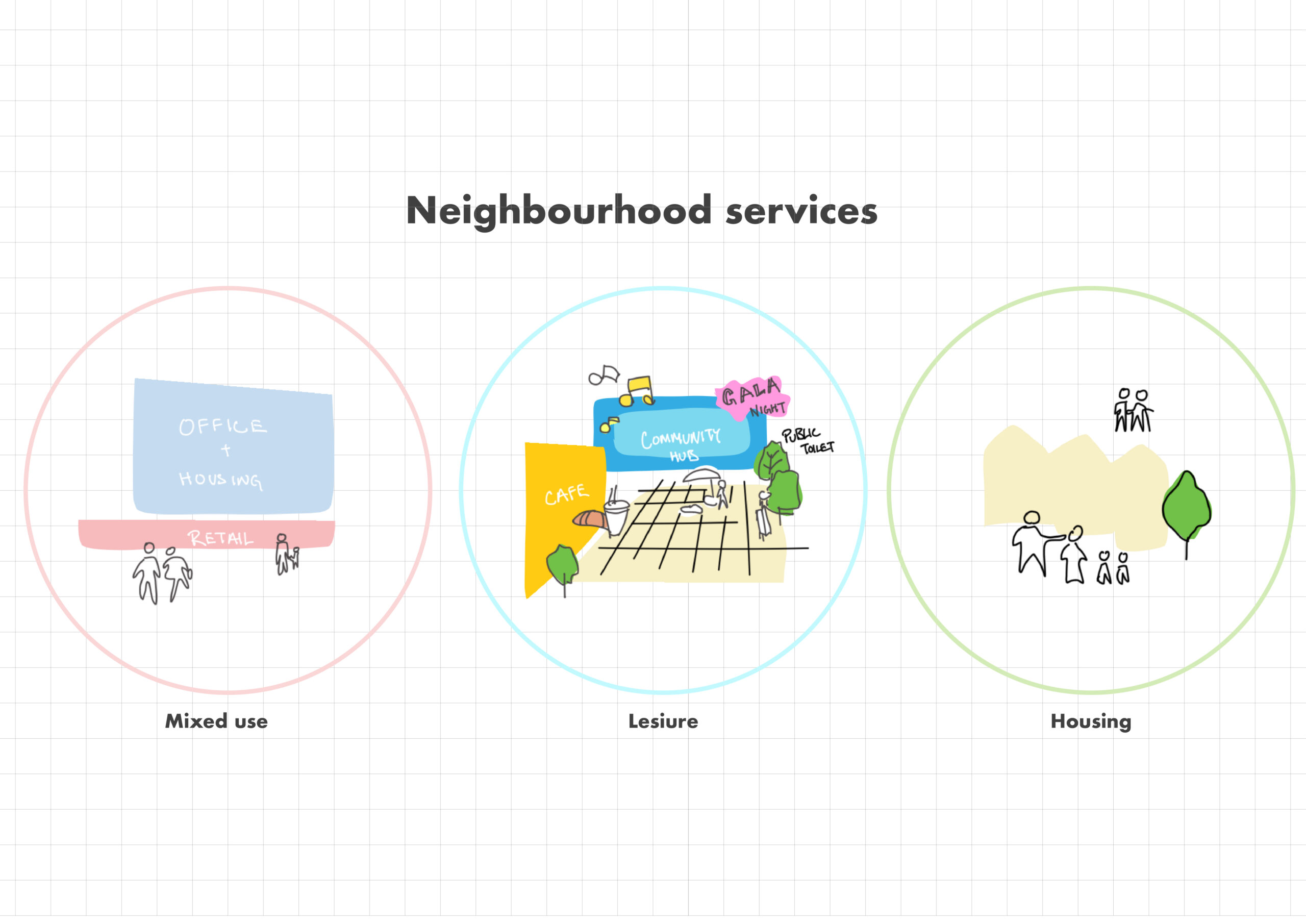

Based on Peace’s research (1982), older adults are greater inclined to access local services such as grocery stores or health centres that are near their residence. To accommodate this need for proximity, the concept of the 15-minute neighbourhood (which is featured in Graeme’s blog) could be a useful concept to employ, providing for the coverage of all amenities within each neighbourhood. However, it is important to remember that one must think about the requirements of the average senior citizen, and not those of the average healthy adult.

Neighbourhood services. Illustration by Luke Leung

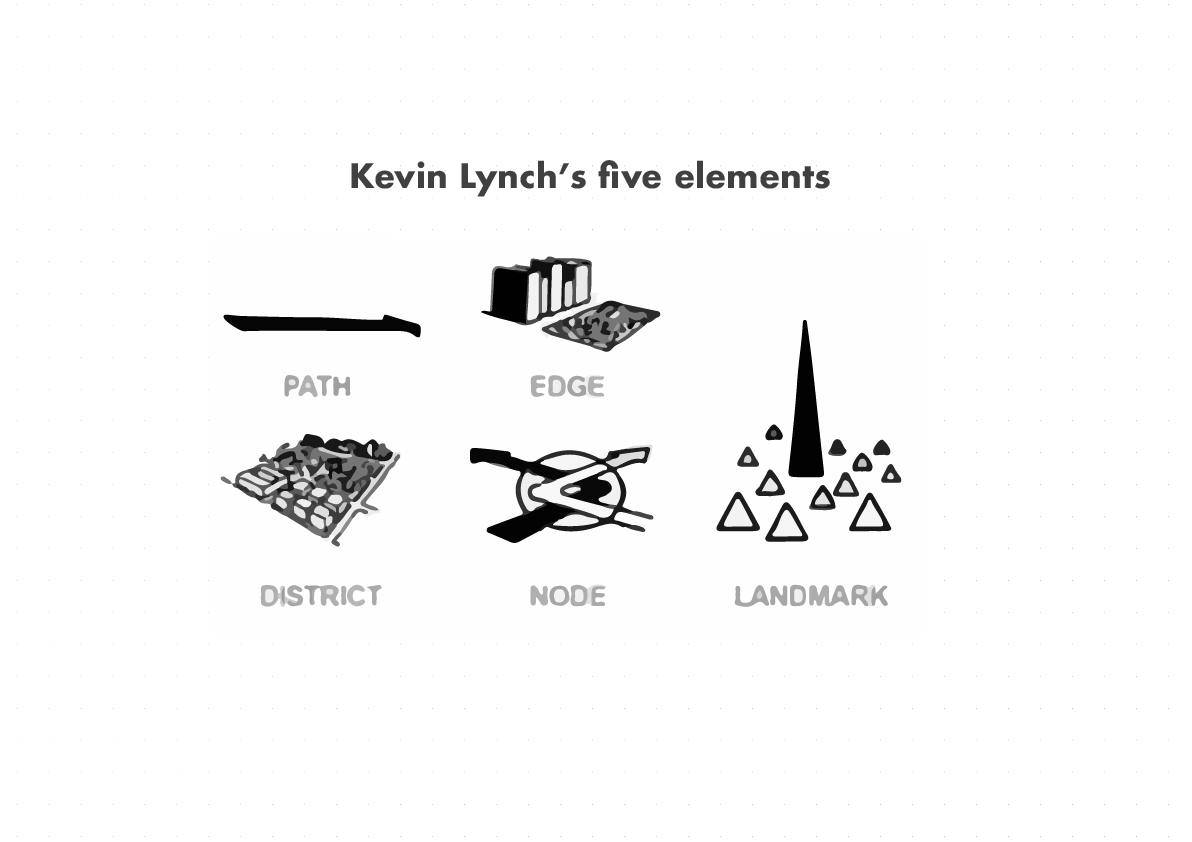

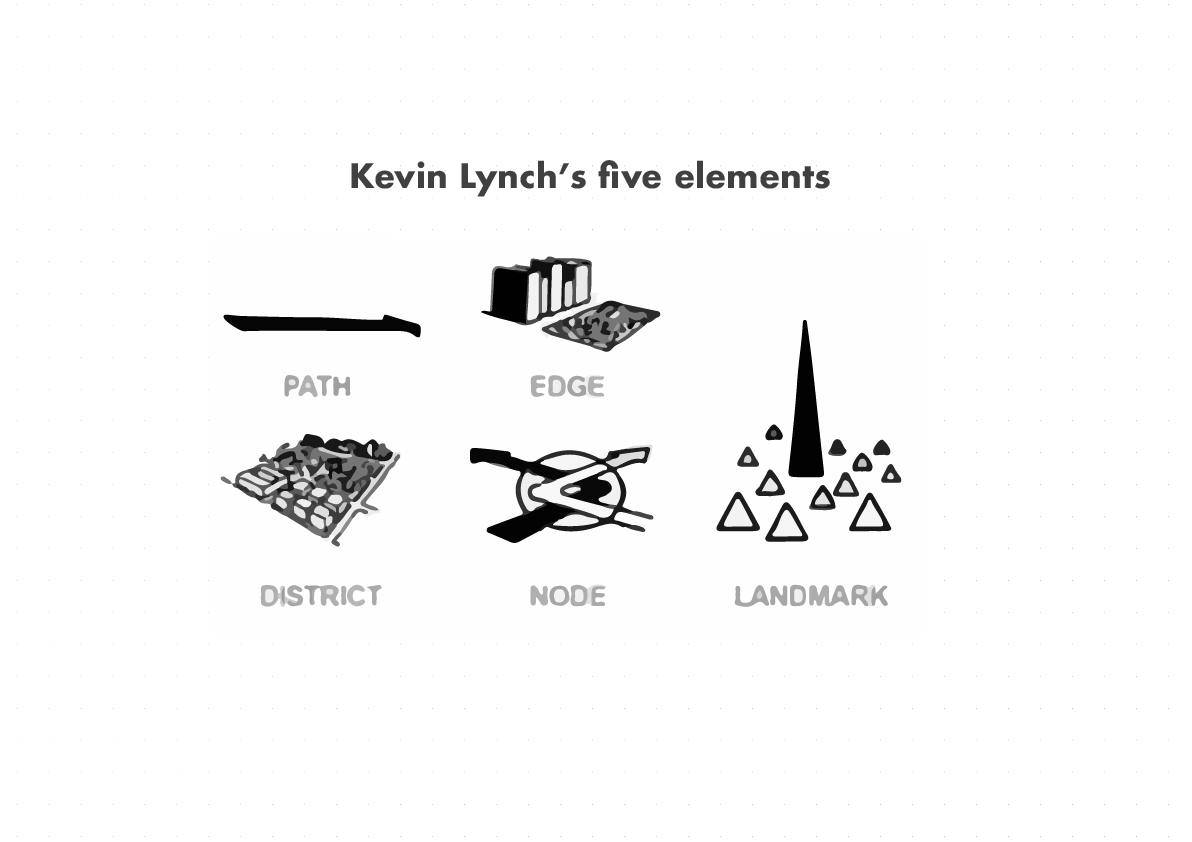

On a smaller scale, the lack of essential public facilities (public restrooms, seating etc.) may seemingly be insignificant to the average healthy adult. Yet, are critical for the experiences of the elderly using public spaces (Lavery et al., 1996., Yücel, 2019). Many older people have chosen to not travel to new locations because of the lack of these facilities, illustrating a crucial factor of just how important they are. Additionally, older adults could also be fearful of not finding their way around unexplored territory. Resulting in reduced willingness to investigate unknown areas. Hence, the importance of designer’s expertise to help create an imageable and psychological place as could be experienced with Kevin Lynch’s book, ‘The Image of the City’ (Lynch, 2014).

Kevin Lynch’s five elements (Lynch, 2014). Illustration by Luke Leung

Age friendly sensory perception

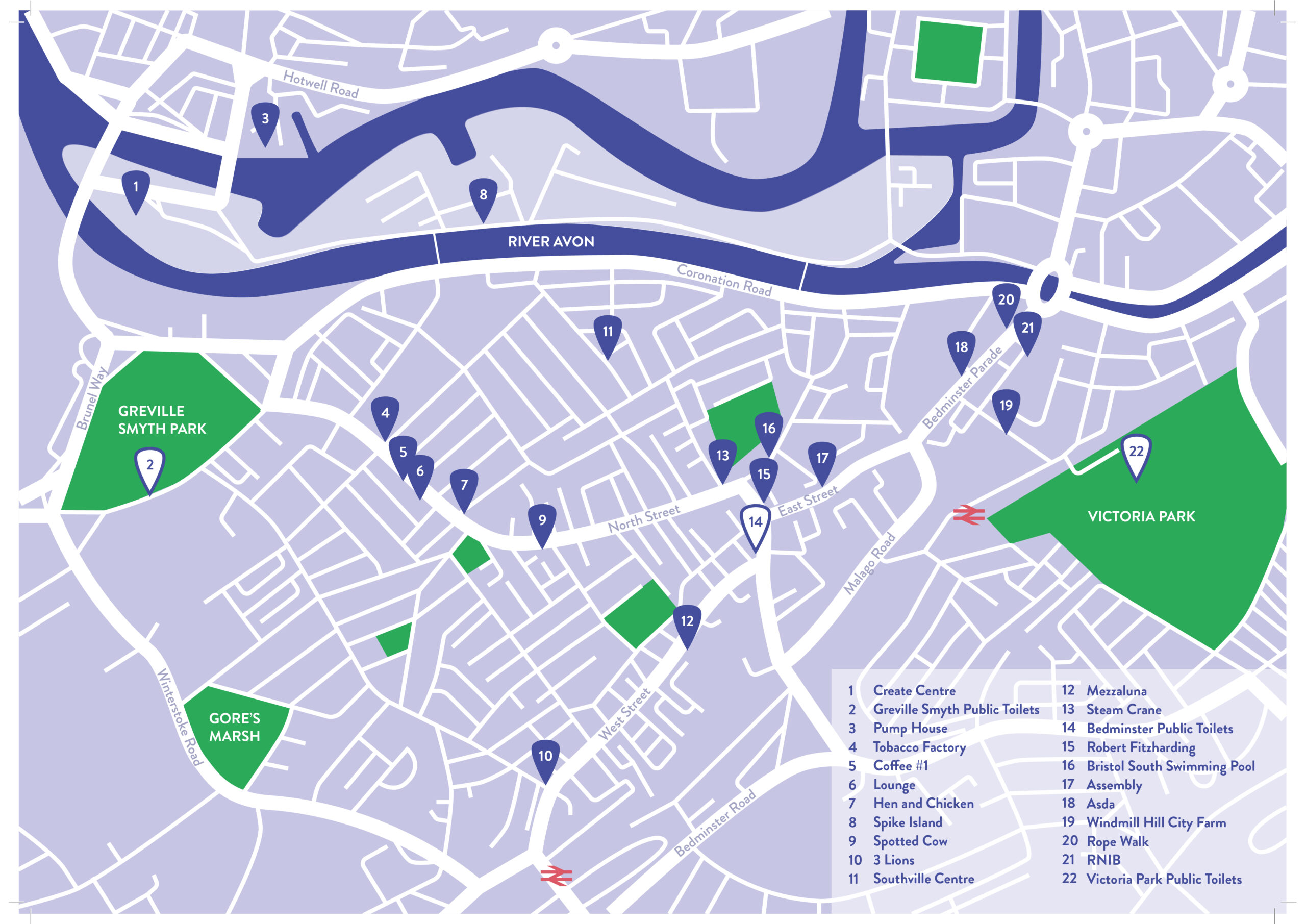

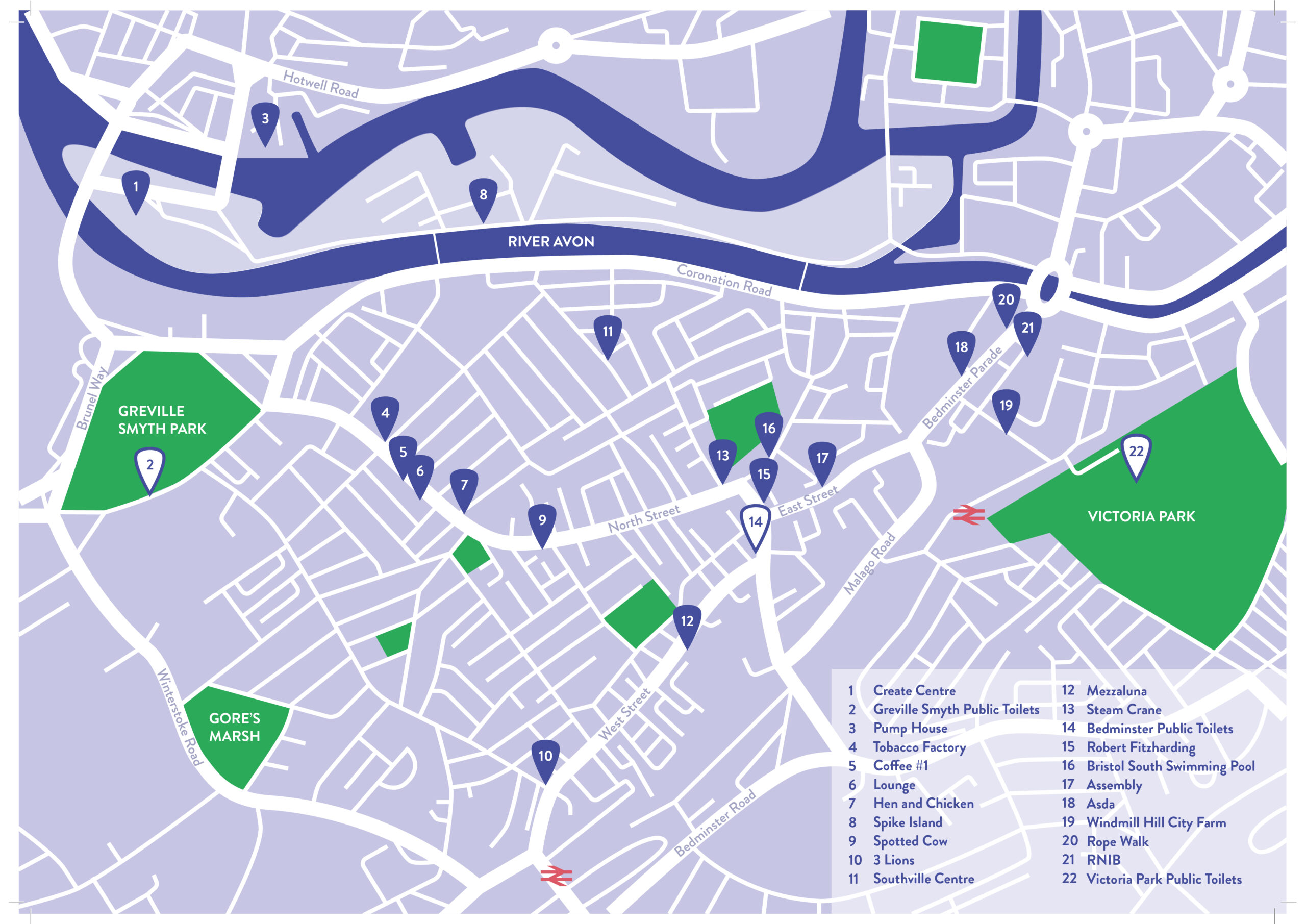

The playful ‘Bedminster Toilet Map’ is an example that symbolises just one way we can enable age-friendly spaces (Sieling, 2017). In addition to this, it is critical to make public places accessible as obstacles such as irregular or steep paths, or bad lighting frequently impede older individuals with mobility, hearing or vision impairments from safely and comfortably using public spaces (Lavery et al., 1996). Whereby, good recognisable elements are key to creating an place attachment, as Gibson (1966) suggests: visual, auditory, taste-smell, haptic, and basic-orientation.

‘Bedminster Toilet Map’ (Tess-sieling, 2017)

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is a prerequisite to age-friendly spaces to not only include essential public facilities in public space, but also to make these enforce the location of such as spaces. Accessibility and locality are main contribute to a sensory perception and place attachment especially for ageing communities.

References

Burton, E. & Mitchell, L. (2006) Inclusive Urban Design: streets for life. Oxford: Elsevier Ltd, pp.49-115.

CIHT (2015) Planning for Walking. London: Chartered Institution of Highways & Transportation. Available at: https://www.ciht.org.uk/media/4465/planning_for_walking_-_long_-_april_2015.pdf (Accessed: 3rd April 2022).

Gibson, J. (1966) The senses considered as perceptual systems. Oxford, England: Houghton Mifflin

Lavery, I., Davey, S., Woodside, A. and Ewart, K. (1996) The vital role of street designand management in reducing barriers to older people’s mobility. Landscape and Urban Planning, 35 (2–3), pp.181–192.

Lynch, L. (2014) The Image of the City. Boston: Birkhauser.

Peace, S. (1982). ‘The activity patterns of elderly people in Swansea, South Wales, and South-East England’ in Warnes, A. (ed.) Geographical Perspectives on the Elderly. Chichester: John Wiley, pp.281–301.

Sieling, T. (2017) The Toilet Map of Bedminster. Bedminster: Minuteman Press. Available at: https://bristolageingbetter.org.uk/userfiles/files/bedminster%20toilet%20map.pdf.

Tess-sieling. (2017) ‘Bedminster Toilet Map’. Minuteman Press. Available at: https://bs3community.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/bedminster-toilet-map.pdf (Accessed: 10th April 2022)

Yücel, G. (2019) Street furniture and amenities: Designing the user-oriented urban landscape. In M. Özyavuz, Advances in Landscape Architecture. Available at: https://www.intechopen.com/books/advances-in-landscape-architecture/street-furniture-and-amenities-designing-the-user-oriented-urban-landscape (Accessed: 3rd April 2022).

This is a very insightful blog about the aging community. I agree with the point that a new urban space must be designed with the resolve of these issues based on various social problems led by an aging society. Urban elements don’t always seem to be age friendly. Obstacles in urban setting. must be considered in order to provide pleasantness environments for all.

As you pointed out, It is important to the experience of older people, although it may not be a problem for the average healthy adult. Automated checkout machines put off about a quarter of older people from going shopping, a survey from a housing charity for the elderly suggests. They can find the automated checkouts “intimidating” and “unfriendly,” according to the charity, Anchor. It also warned that automated checkouts could add to loneliness and isolation among the elderly (Coughlan, 2017).

Therefore, I think the suggestion of ‘Bedminster Toilet Map’ is a brilliant idea. It is crucial to provide accessibility where elderly feel safer, more convenient way. I also start to think how this goal can be achieved, beyond simply providing physical convenience to the elderly, it should be a way for them to feel a sense of belonging to this society.

References

– Coughlan, Sean. “Automated Checkouts “Miserable” for Elderly Shoppers.” BBC News, 21 Nov. 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-42052234.

Agree with you. We need to think more about how older people are living their lives. Being attentive to the needs of each group is also essential for a good designer to be able to both.

Physiological mobility: Compared to younger people, older people have weaker eyesight, so signs etc. need to be recognisable enough to use bright colours. At the same time, older people may need wheelchairs to assist with mobility, so they need to be clearly identified by bright colours on steps and other areas. “Research has shown that the quality of the outdoor environment is closely related to important health-related measures and behaviours. For example, Figure 8 shows that features with minimal impact (‘the outdoors is fully accessible via paved walkways’) still significantly increased the amount of time older people spent outdoors, by 51 minutes per week. Anyone who has worked with older people in a residential care setting knows how difficult it can be to influence habits such as outdoor use or physical activity, and this would be a huge improvement. Figure 9 shows that the environmental feature with the greatest impact (“outdoor areas with great views of birds and wildlife”) was associated with a nearly 10-fold increase in outdoor use – from 118 minutes per week to 1,032 minutes per week.” –Texas A&U team

Reference:

Access to Nature for Older Adults: Promoting Health Through Landscape Design(https://www.asla.org/2010awards/564.html)

This blog remind me of the UK Network of Age-frendly Communities.The UK Network of Age-friendly Communities is a growing movement with over 50 member places across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The UK Network is affiliated to the World Health Organisation’s Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities.

An Age-friendly Community is a place where people of all ages are able to live healthy and active later lives. These places make it possible for people to continue to stay living in their homes, participate in the activities that they value, and contribute to their communities, for as long as possible.

The Age-friendly Communities Framework was developed by the World Health Organisation, in consultation with older people. It is built on the evidence of what supports healthy and active ageing in a place.

In these communities, older residents help to shape the place that they live. This involves local groups, councils, businesses and residents all working together to identify and make changes in both the physical and social environments, for example transport, outdoor spaces, volunteering and employment, leisure and community services.

They work with the Network to facilitate and give a platform for local areas to share and discuss what kinds of approaches work, both in the UK and internationally.

Through various channels and resources (such as case studies, peer meetings, conferences and workshops), we provide guidance, connect places and offer support to member communities in their efforts to become more age-friendly.

reference:https://ageing-better.org.uk/

China is one of the countries with a relatively high degree of population aging in the world. It has the largest number of elderly people and the fastest aging rate, and the task of dealing with population aging is the heaviest. According to the data of China’s seventh national census, China’s elderly population aged 60 and above is 264.02 million, accounting for 18.7% of the total population. It is estimated that China’s population over the age of 60 will exceed 300 million in 2025 and 400 million in 2033. China is about to enter a moderately aging society. To meet the multifaceted needs of the increasingly large number of elderly people and properly solve the social problems brought about by population aging requires the joint efforts of the whole society to deal with it.

With the decline of the physical function of the elderly and the increase of the probability of illness, the demand for medical care and daily health care is more urgent. However, the current lack of medical care and nursing care cannot meet the needs of the elderly. The main manifestations are: 78.5% of the elderly have one or more chronic diseases, mainly cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and sports system diseases, but only 68.3% of the elderly have established community health records; More than 90% of communities lack medical and health service personnel, including general practitioners and professional nurses; third, grassroots medical institutions lack enforcement, and can only provide routine services such as regular physical examinations and health lectures for the elderly. More professional services such as rehabilitation nursing, psychological counseling, and emergency rescue cannot be provided; fourth, the health awareness of the elderly is relatively weak, and they lack correct and reasonable health behaviors and living habits.

References:

– Lin Bao: “Analysis of the Current Situation and Trend of the Elderly Population Who Can’t Take Care of Theirself in China”, April 2015