How can we encourage active travel through urban design?

The Government state that inactivity contributes to 1 in 6 deaths across the UK (Public Health England, 2016). Additionally, it is reported to cost an estimated £7.4 billion yearly (Public Health England, 2016).

Active travel is defined as physical travel such as walking and cycling. With over a quarter of adults reporting less than 30 minutes of physical activity per week in England (Public Health England, 2016), considering how environmental determinants influence active travel behaviours is essential.

“Active Travel infrastructure – Auckland, New Zealand” by sustainablejill is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Does the environment influence active travel?

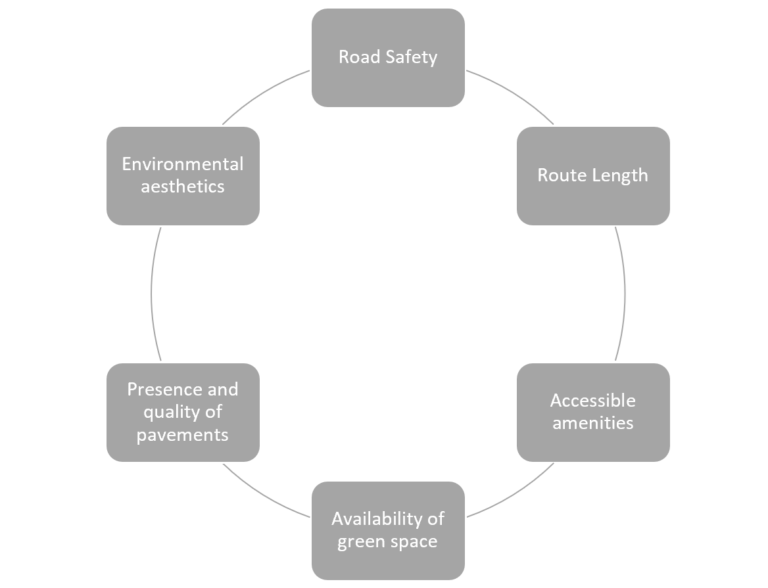

Research indicates a correlation between physical activity and physical environments (Ogilvie, 2008). The most common environmental factors noted as impacting physical activities are shown below (Ogilvie, 2008).

Kerr et al indicate that aesthetically pleasant neighbourhoods were 2.5 times to have active travel (Parker, 2008).

Ankara, Turkey

ARUP have transformed Ankara, Turkey from a city with the highest level of car ownership in the country to a cycling haven (ARUP, 2022). A vital element of this was to engage customer groups and tailor the design to different needs. For example, youths may view cycling as a leisure activity (ARUP, 2022). Whereas for adults, cycling should form part of a wider transport network helping users access amenities (ARUP, 2022). Design solutions included; minimising interaction between cyclists and cars, reducing traffic speeds and connecting public transport (ARUP, 2022).

“Ankara, Turkey” by Minamie’s Photo is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

How do we design for active travel?

Ankara places emphasis on the need to engage users in creating active neighbourhoods. This is supported by Hutchinson and Graham, who indicate that different approaches are required for rural and urban areas (Hutchinson & Graham, 2014). This is due to different levels of access to transport and varying travels distances, with rural communities relying more on the private car (Hutchinson & Graham, 2014).

Furthermore, the most essential environmental determinant I have found from my research is the need for safety and access to amenities. However, there is a disparity in the influence of environmental factors and active travel depending on level of car ownership. For example, in more deprived areas in Glasgow, Ogilvie determined environmental factors had limited influence over active travel due to reduced travel choices (Ogilvie, 2008). There is no one-size-fits-all approach and design solutions should change depending on community needs, but user engagement is essential.

References

- Minamie’s Photo (2009) Ankara, Turkey [online image] Available at: https://wordpress.org/openverse/image/3b6cf615-b59d-4b58-887c-246f2ec820f9 (Accessed on 15/05/22)

- Sustainablejill (2016) Active Travel infrastructure – Auckland, New Zealand. [online image] Available at: https://wordpress.org/openverse/image/86aa65eb-2ac8-4dde-92c1-f5ec371f3384 (Accessed on 15/05/22)

- Sustainablejill (2016) Active Travel infrastructure – Auckland, New Zealand. [online image] Available at: https://wordpress.org/openverse/image/4f46d3e9-6691-46d9-80b9-575b96df1da5 (Accessed on 15/05/22)

- Panter, J. et al (2008) Environmental determinants of active travel in youth: A review and framework for future research. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity. Vol 5. Article number: 34.

- Ogilvie, D. et al (2008) Personal and environmental correlates of active travel and physical activity in a deprived urban population. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity. Vol 5. Article number: 34.

- Hutchinson, J., White, P.C.L. & Graham, H. (2014) Differences in the social patterning of active travel between urban and rural populations: findings from a large UK household survey. International Journal Public Health. Vol 59. pp 993–998.

- Public Health England (2016) Working Together to Promote Active Travel A briefing for local authorities. [online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/523460/Working_Together_to_Promote_Active_Travel_A_briefing_for_local_authorities.pdf (Accessed on 10/05/22)

- ARUP (2022) A city on two wheels: how to encourage inclusive active travel. [online] Available at: https://www.arup.com/perspectives/a-city-on-two-wheels-how-to-encourage-inclusive-active-travel (Accessed on 05/05/22)

Louise blogs to us about the importance of active travel and the dangers of lack of exercise. As a world, ‘shared spaces’ may be an important element if we want to get cities moving. In the beginning ‘shared spaces’ were designed to provide a safe environment for children on the streets. Later the Netherlands defined it more broadly as a residential street that creates a good environment to emphasise that the function of the area is residential at its core and focuses more on the social street space with ‘people’ at its core. (Shishi Kang, 2021)

A good example might be St Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square in Sweden, located in the Triangeln area of Malmo, where the White Company used lighting, outdoor seating, vegetation and other elements to connect the street, landscape and square. It gets busy people out of their office buildings and into the outdoors.

The core concept of the shared space is to transform the street from a transportation function to a social function that allows for recreation, gathering, leisure and a green environment as well as an artistic aesthetic. Traffic functions, such as motor vehicles and motorbikes, need to make concessions to the subjective ideology of pedestrians and cyclists in the design of shared spaces.

1.https://link.zhihu.com/target=http%3A//www.gooood.hk/st-johannesplan-the-konsthall-square-by-white.htm

2.https://www.zhihu.com/question/52798618/answer/132351730

Louise , that is indeed a very insightful topic and a most pressing issue to be discussed. It is scary that UK people have only approx 30 mins of physical activity in a week which explains all the deaths because of inactivity. Fortunately, with the pandemic from 2019 to 2020 there is a rise of 23% of cycling stages in England. And in general the proportion of walking trips in relation to other transport modes increased in 2020, people made 32% of all their trips by walking in 2020 compared to 26% in 2019.

Me, personally being from India where there is least provision made for the cities towards sustainable transport,because of its over population and other financial constraints. Ever since I came here to Uk I have walked more in the first 3 months than I have ever walked in my entire lifetime in India. I wonder what is the reason behind this difference, if not for the weather conditions.

Similar to your example I would like to add an example to this context. In Denmark, people bicycle in all types of weather and at all times of day. Bicycles are used for pleasure, commuting, transport of goods, and family travel. In the big cities, it is often easier to commute by bike than by car. Denmark Is considered as the world’s best cycling country. Almost one third (29%) of all journeys across Copenhagen are done on a bike, and 41% of commutes are the result of pedal power.

References:

https://www.cyclinguk.org/statistics

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/walking-and-cycling-statistics-england-2020/walking-and-cycling-statistics-england-2020

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/906698/walking-and-cycling-statistics-england-2019.pdf

https://denmark.dk/people-and-culture/biking?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=biking

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/10/what-makes-copenhagen-the-worlds-most-bike-friendly-city/