Community engagement: Fenham Futures

Photograph by Luke Leung

In the recent decade, community planning has been rising in popularity as planners and local authorities, architects and other practitioners can all benefit from social discussion into shaping their local environment. Wates (2014) suggested, growing numbers of residents and communities are getting involved with professionals in shaping their environment. These involvements are often developed from design workshop to electronic maps.

In middle of May 2022, I attended an undergraduate event by AUP (Architecture and Urban Planning) student initiative in Alternative Practice: Co-producing Space (Ncl, n.d). This module by encourages students to explores the role of socially engaged spatial practitioner in an community-led placemaking. This live project enables first-hand experience into the practical field of community engagement. Combining theories, case studies and approaches learnt through the alternative practice rather than traditionally planning method can allows us to redefine architecture and the limited discourse of surrounding, providing an alternative insight into various approaches to the production of buildings and spaces (Awan et al, 2011).

Social discussion. Photograph by Luke Leung

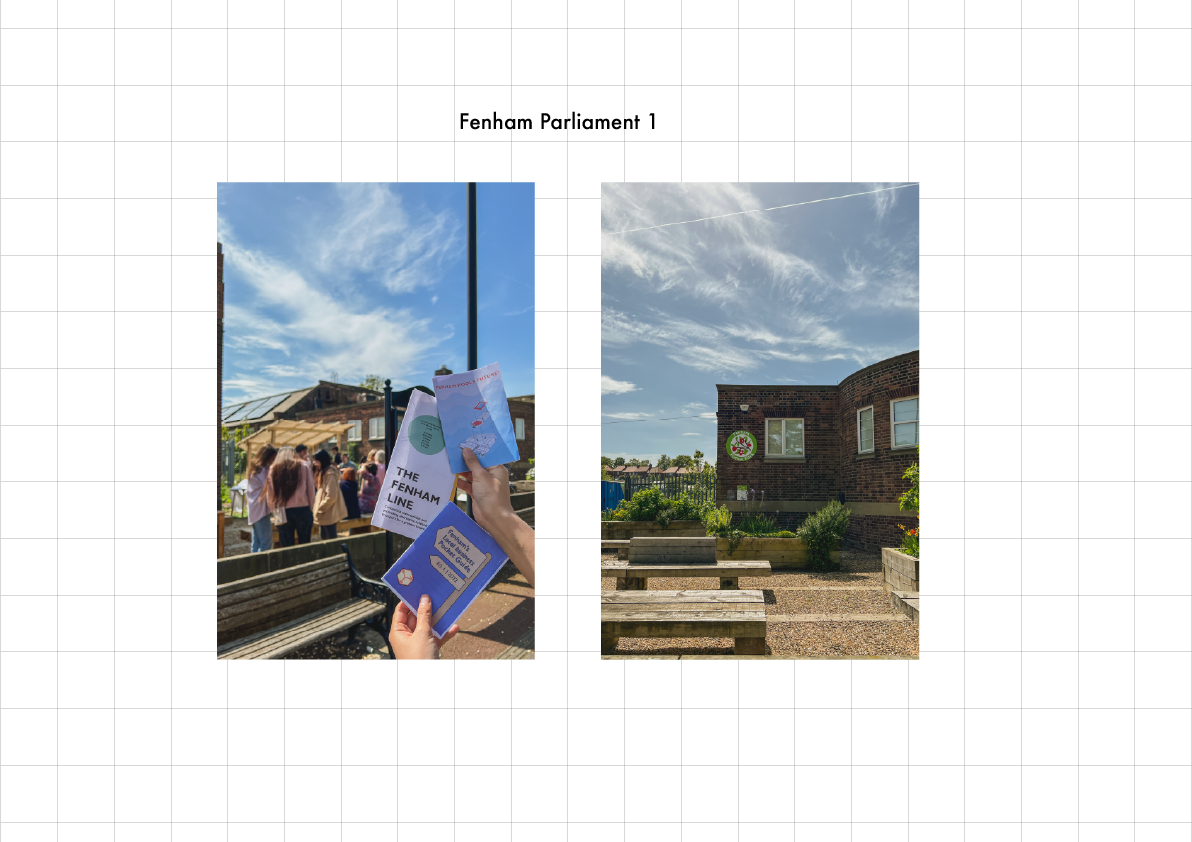

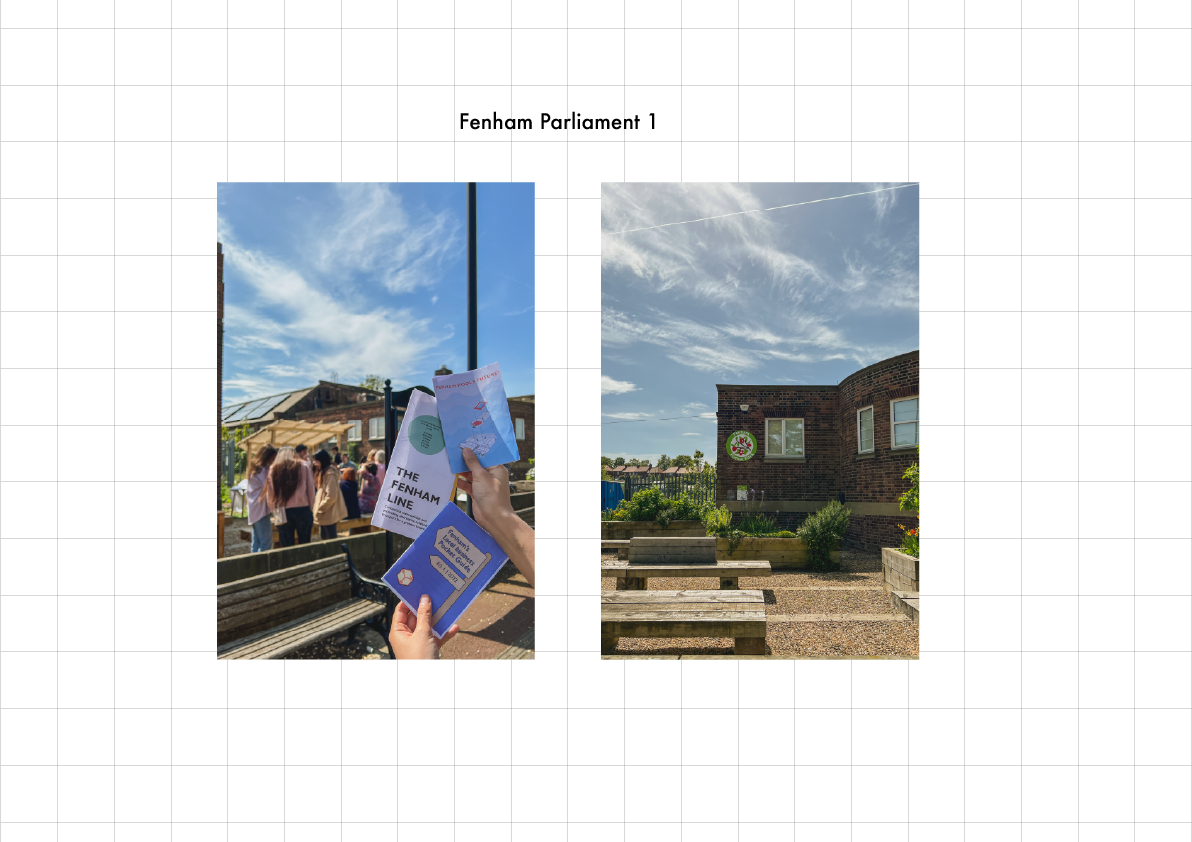

This year, AUP students held the “Fenham Futures Parliament” (Fenham Futures, 2022). This event took place in Northwest of Newcastle City Centre, Fenham Pocket Park (Mallo & Tardiveau, 2020). The students held discussions with the local communities focused on Heritage and creative reuse, Social economy, and Climate Futures. This collaborative project hope to aspires further engage the local communities strengthening connections of Fenham Pocket Park, stakeholders and local residents. Create a greener Fenham and extend the breath of activities in and around the park to make it more enchanting and welcoming space for everyone.

Fenham Parliament 1.1. Photographs by Luke Leung

Fenham Parliament 1.2. Photographs by Luke Leung.

Engagement with contributors – community groups, individual members, local residents, stakeholders and businesses alike – can discuss a wide range of recreational, commercial and political activities (Franck & Stevens, 2006). In event like Fenham Parliament 1 by AUP, the informal atmosphere help strengthen social cohesion as conversations among contributors are more relaxed, therefore people are more willingly to discuss social and physical constraints among the spatial practice. The aspect of social capital and social cohesion is mostly grounded on mutual trust and the ability to create changes and exercise informal social control (Health People 2030, n.d).

Among the conversations, people discussed how Fenham Pock Park, former Fenham swimming pool, Fenham library and the connecting allotment space can be better explored and be used people of all ages. It is in these realm of public spaces, key theme in urban design and further development can unfold, and further how they bring people together, to inspire appreciation and be used in everyday life in urban neighbourhoods (Madanipour, 2010).

Fenham Pocket Park + surrounding. Illustration by Luke Leung.

In conclusion, community engagement matters as this encourages people to rally behind ideas, but also being contested by and under pressure from different stakeholders to act on public spaces and surrounding areas. Event such as AUP Fenham Parliament are key conversation starter, by hosting gathering it enable talk to be taken into action! Where social challenges and connections can then be develops into spatial practice.

Wild flower seeds. Photographs by Luke Leung

For more information about Fenham Futures, please visit https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/fenhamfutures/

Reference

Awan, N., Schneider, T. & Till, J. (2011) Spatial agency: other ways of doing architecture. London: Routledge.

‘APL3001: Alternative Practice: Co-producing Space’ (no date) Available at: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/undergraduate/degrees/module/?code=APL3001 (Accessed 17th May 2022).

Fenham Futures. (2022) Fenham Futures: Communities reimaging social and climate futures in Fenham. Available at: https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/fenhamfutures/about/ (Accessed 17th May 2022).

Franck, K. & Stevens, Q. (2006) Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life. New York: Routledge.

Healthy People 2030. (no.date) ‘Social Cohesion’. Available at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/social-cohesion (Accessed 23rd May 2022).

Madanipour, A. (2010) Whose public space?: International case studies in urban design and development. London: Routledge.

Mallo, D. & Tardiveau, A. (2020) Fenham Pocket Park Design Activism: a Catalyst for Communities of Practice. Available at: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/mediav8/apl/files/201210_Fenham%20Pocket%20Park_rev%20dm-at_draft_low-res_revision%20Dec%202020.pdf (Accessed 24th May 2022).

Wates, N. (2014) The Community Planning Handbook: how people can shape their cities, towns and villages in any part of the world. London: Routledge. Second edition

[…] can read an account of the day by Luke Leung (MA Urban Design), who attended on the day and wrote up his experiences for the NCL Urban Design blog – along with some lovely photos! […]

Community engagement is a crucial yet underused approach to design. The Fenham Futures project is a great example of this. As you said, it facilitates ‘greater social cohesion’ within a community. This then leads to more honest and representative design, where the outcome will adhere to the needs and wants of the community.

However, it is often the case that the engaged members of the community do not represent the target demographic. One reason for this is digital incompetence. The Office for National Statistics (2018) certified that 10% of the UK adults were ‘non internet users.’ This is a consequence of ‘The Digital Divide’. Despite this, experts predict a future of tech-induced informed participation and shared knowledge (Batty et al, 2012). Thus, ‘The Digital Divide’ needs resolving to stop these predictions from becoming historic cases of overoptimism and unrealistic ambition.

Once we overcome this hurdle, decision makers will better understand the interlinkages and nature of problems facing the city. Also, consensus will be built. This greatly enhances political interaction between citizens and government and enhances the legitimacy of the planning process and the plan itself (UN-Habitat, 2018).

Unsurprisingly then, places derived from collaboration and community are on the horizon. Therefore, initiatives like ‘Fenham Futures’ are setting the standard for community-engaged design strategies to come.

References:

Batty, M., Axhausen, K. W., Giannotti, F., Pozdnoukhov, A., Bazzani, A., Wachowicz, M., … & Portugali, Y. (2012). Smart cities of the future. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 214(1), 481-518. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1140/epjst/e2012-01703-3 (Accessed: 21st April 2022).

The Office for National Statistics (2018) Internet Users, UK, 2018. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/itandinternetindustry/bulletins/internetusers/2018 (Accessed: 21st May 2022).

UN-Habitat (2018). SDG Indicator 11.3.2 Training Module: Civic Participation. United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2021/08/indicator_11.3.2_training_module_civic_participation.pdf (Accessed: 21st April 2022).