This is an interesting blog post regarding child-friendly urban space. Because of the neglect of children in public space areas, outdoor spaces are beginning to address child-centred settings and seek to support children’s mental healthy development through chance for outdoor play. According to Hinkley et al. (2008). Outdoor play is particularly important for children’s geography and health.

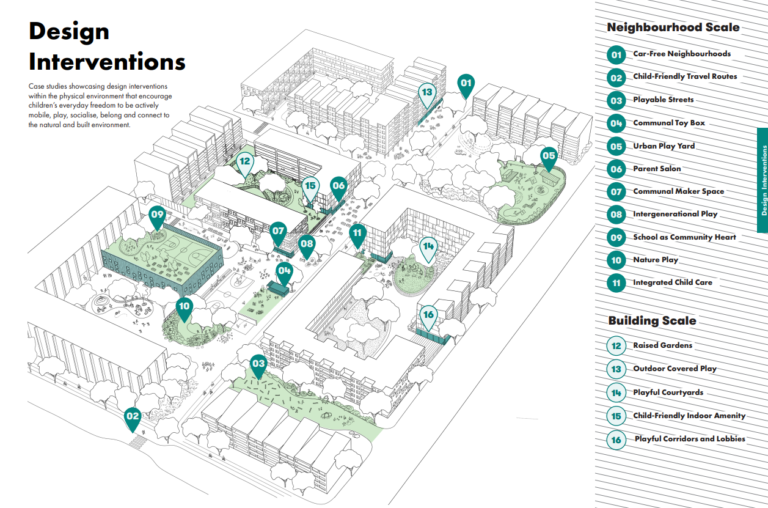

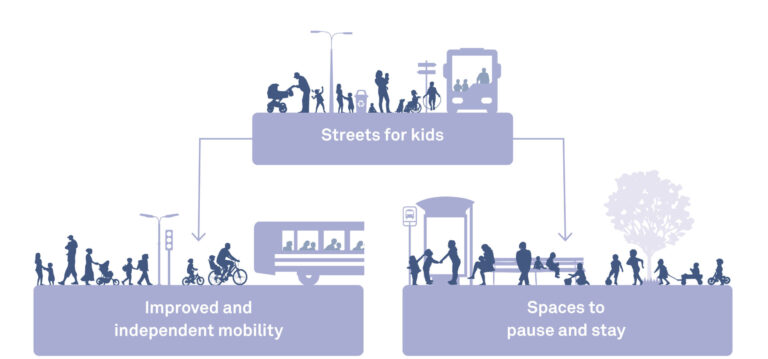

child-friendly urban space idea has prompted designers to rethink the meaning of the child-friendly design, which takes into account not only safety but also Diversity of amenities and green areas. In terms of safety, the majority of children are in designated play spaces such as parks and playgrounds rather than less safe places such as streets (Hinkley et al., 2008). Diversity Amenities also play an important role. According to Krishnamurthy (2019), both parents and children want diversified play environments, such as in nature, sports, and playgrounds, with varying enrichment for different age groups. As a result, safe location and diversity of amenities activity areas are more likely to be popular with both children and parents, with large spaces and an abundance of amenities encouraging children to get out and play. Seating is also required in activity areas to keep parents company and to keep an eye on them. Green space is also a crucial factor to consider; more exposure to green space can lower stress, exhaustion, and anxiety, as well as bring wellness to the body and mind (Hartig et al., 2014). The availability of green space, particularly for small children, promotes play and has a crucial role in children’s cognitive development and socialisation (Louv Citation 2005). According to Krishnamurthy (2019), even if there are no children’s facilities within the park, it will attract children provided there is a vast green space, and they will create their activities in the green space and use the space more flexibly. This is due to the fact that play in natural contexts is more sensual and exploratory than play in non-natural environments (Berg, Koenis, & Berg Citation 2007). As a result, green spaces are both child-friendly and vital. Child-friendly space characteristics extend well beyond amenities and green space; identify and create a child-friendly place with the kid’s belongings through continual exploration and observation.

Reference:

Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., de Vries, S. and Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and health. Annual review of public health, [online] 35(1), pp.207–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443.

Hinkley, T., et al., 2008. Preschool children and physical activity: a review of correlates. American journal of preventive medicine, 34 (5), 435–441. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.001

Krishnamurthy, S. (2019). Reclaiming spaces: child inclusive urban design. Cities & Health, 3(1-2), pp.1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2019.1586327.

Louv, R., 2005. Last child in the woods. North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

van den Berg, A.E., Koenis, R., and van den Berg, M.M.H.E., 2007. Spelen in het groen. Effecten van een bezoek aan een natuurspeeltuin op speelgedrag, de lichamelijke activiteit, de concentratie en de stemming van kinderen. Wangeningen: Alterra.

This is an interesting blog post regarding child-friendly urban space. Because of the neglect of children in public space areas, outdoor spaces are beginning to address child-centred settings and seek to support children’s mental healthy development through chance for outdoor play. According to Hinkley et al. (2008). Outdoor play is particularly important for children’s geography and health.

child-friendly urban space idea has prompted designers to rethink the meaning of the child-friendly design, which takes into account not only safety but also Diversity of amenities and green areas. In terms of safety, the majority of children are in designated play spaces such as parks and playgrounds rather than less safe places such as streets (Hinkley et al., 2008). Diversity Amenities also play an important role. According to Krishnamurthy (2019), both parents and children want diversified play environments, such as in nature, sports, and playgrounds, with varying enrichment for different age groups. As a result, safe location and diversity of amenities activity areas are more likely to be popular with both children and parents, with large spaces and an abundance of amenities encouraging children to get out and play. Seating is also required in activity areas to keep parents company and to keep an eye on them. Green space is also a crucial factor to consider; more exposure to green space can lower stress, exhaustion, and anxiety, as well as bring wellness to the body and mind (Hartig et al., 2014). The availability of green space, particularly for small children, promotes play and has a crucial role in children’s cognitive development and socialisation (Louv Citation 2005). According to Krishnamurthy (2019), even if there are no children’s facilities within the park, it will attract children provided there is a vast green space, and they will create their activities in the green space and use the space more flexibly. This is due to the fact that play in natural contexts is more sensual and exploratory than play in non-natural environments (Berg, Koenis, & Berg Citation 2007). As a result, green spaces are both child-friendly and vital. Child-friendly space characteristics extend well beyond amenities and green space; identify and create a child-friendly place with the kid’s belongings through continual exploration and observation.

Reference:

Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., de Vries, S. and Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and health. Annual review of public health, [online] 35(1), pp.207–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443.

Hinkley, T., et al., 2008. Preschool children and physical activity: a review of correlates. American journal of preventive medicine, 34 (5), 435–441. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.001

Krishnamurthy, S. (2019). Reclaiming spaces: child inclusive urban design. Cities & Health, 3(1-2), pp.1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2019.1586327.

Louv, R., 2005. Last child in the woods. North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

van den Berg, A.E., Koenis, R., and van den Berg, M.M.H.E., 2007. Spelen in het groen. Effecten van een bezoek aan een natuurspeeltuin op speelgedrag, de lichamelijke activiteit, de concentratie en de stemming van kinderen. Wangeningen: Alterra.

This is a very descriptive blog about child centric urban spaces. As birth rate has declined throughout the world, the importance of child-friendly spaces is less likely to be considered (Giraldi et al, 2017).

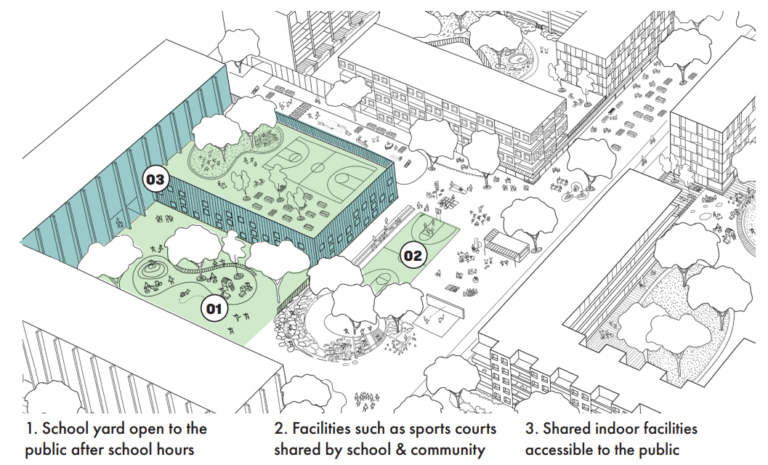

Nishita’s blog dealt with issues resulted from urbanisation, which causes the lack of child-friendly outdoor spaces. The blogger suggested the use of schoolyard and the develop-ment of streetscape for children’s activities. I agree with those ideas. A study conducted Lopez et al (2008) shows that re-designing schoolyards can offer recreational places for children, parents and the community as an activity space while strengthening relationships within urban space. Most schoolyards are closed because of safety reasons but it seems to be an ideal place for activities in an urban area where it is challenging to secure certain places for creating open space. In addition, students and neighbourhoods who are in poor condition are disadvantaged by infrastructure deficit. Considering this, facilitating schoolyards as a community place prevents eruptions of violence for children while reduc-ing the budget to create open space.

The Boston Schoolyard Initiative is a good example of proposal. Newly constructed parks in school yards appear to invite communication, interaction and activities after school, which tackle economic, social and environmental issues (INITIATIVE, BOSTON SCHOOLYARD, 2015). Thus, the lack of child-friendly outdoor spaces can be achieved through transforming schoolyard into a space for children’s activities within urban area and it also has a positive effect on the mental well-being of urban residents especially parents and the elderly groups.

Reference lists

INITIATIVE, B. S. (2015). Outdoor classroom user’s guide. http://schoolyards.org/pdf/OutdoorClassroomUsersGuide.pdf.

Lopez, R., Campbell, R., & Jennings, J. (2008). The Boston Schoolyard Initiative: A Public-Private Partnership for Rebuilding Urban Play Spaces. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 33(3), 617–638. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2008-010

Giraldi, L, et al. (2017). Designing for the next generation. Children urban design as a strate-gic method to improve the future in the cities. The Design Journal, 20(sup1), S3068-S3078.