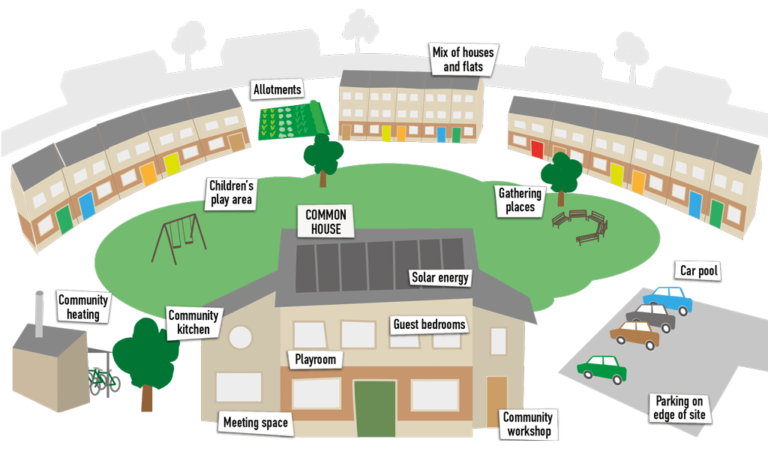

This is an insightful blog post about co-housing. With the use of shared spaces and resources to promote a sustainable way of life, this innovative type of housing not only solves some problems with housing affordability but also improves community cohesion. However, this lifestyle is also semi-opened, residents engage in private activities like cooking and dining together. Resident families are hence regularly exposed to external influences (Wasshede, 2021). Even these open lifestyles can foster connections between the residents’ diverse traditions and cultures, but they can also threaten privacy. Moreover, there may be some privacy invasion associated with high living densities. Baum & Valins (1977) noted that people of high living densities tend to feel less in control of their surroundings, which leads to isolating themselves from the community. It was also mentioned in Altman’s (1975) work that neighbourhoods should close but not become overly crowded. Restrictions on comfort and privacy can be seen in co-housing communities, regardless of the type of lifestyle—high-density housing or semi-open living—which is why buffer zones are crucial. A buffer zone can be established by erecting a threshold between private and public locations to make a protective barrier(Birchall, 1988), or by including semi-private spaces that allow for active contact with neighbouring public spaces ( Skjaeveland et al., 1996). This allows residents to alleviate the community contact and enjoy social interaction while maintaining their privacy.

In conclusion, co-housing offers a good social environment, but residents also lose some privacy due to the semi-open lifestyle. To make co-housing more livable, buffer zones and semi-private spaces can be added to the design to keep residents from being overly exposed to outside influences.

Reference:

Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behaviour: privacy, personal space, territory, crowding. New York: Irvington.

Baum, A. and Valins, S. (1977). Architecture and Social Behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Birchall, J. (1988). Building Communities the Co-operative Way. Psychology Press.

Skjaeveland, O., Gärling, T. and Maeland, J.G. (1996). A multidimensional measure of neighbouring. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24(3), pp.413–435. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02512029.

Wasshede. (2021). Doing family in co-housing communities. In Hagbert, Gutzon Larsen, Thörn, & Wasshede, Contemporary Cohousing in Europe: Towards Sustainable Cities? (pp. 163-182). London: Routledge.

This is an insightful blog post about co-housing. With the use of shared spaces and resources to promote a sustainable way of life, this innovative type of housing not only solves some problems with housing affordability but also improves community cohesion. However, this lifestyle is also semi-opened, residents engage in private activities like cooking and dining together. Resident families are hence regularly exposed to external influences (Wasshede, 2021). Even these open lifestyles can foster connections between the residents’ diverse traditions and cultures, but they can also threaten privacy. Moreover, there may be some privacy invasion associated with high living densities. Baum & Valins (1977) noted that people of high living densities tend to feel less in control of their surroundings, which leads to isolating themselves from the community. It was also mentioned in Altman’s (1975) work that neighbourhoods should close but not become overly crowded. Restrictions on comfort and privacy can be seen in co-housing communities, regardless of the type of lifestyle—high-density housing or semi-open living—which is why buffer zones are crucial. A buffer zone can be established by erecting a threshold between private and public locations to make a protective barrier(Birchall, 1988), or by including semi-private spaces that allow for active contact with neighbouring public spaces ( Skjaeveland et al., 1996). This allows residents to alleviate the community contact and enjoy social interaction while maintaining their privacy.

In conclusion, co-housing offers a good social environment, but residents also lose some privacy due to the semi-open lifestyle. To make co-housing more livable, buffer zones and semi-private spaces can be added to the design to keep residents from being overly exposed to outside influences.

Reference:

Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behaviour: privacy, personal space, territory, crowding. New York: Irvington.

Baum, A. and Valins, S. (1977). Architecture and Social Behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Birchall, J. (1988). Building Communities the Co-operative Way. Psychology Press.

Skjaeveland, O., Gärling, T. and Maeland, J.G. (1996). A multidimensional measure of neighbouring. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24(3), pp.413–435. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02512029.

Wasshede. (2021). Doing family in co-housing communities. In Hagbert, Gutzon Larsen, Thörn, & Wasshede, Contemporary Cohousing in Europe: Towards Sustainable Cities? (pp. 163-182). London: Routledge.

Thank you for this blog regarding co housing and the way it functions in the urban context. The author has approached the topic in a crisp and precise way of communicating with the reader that highlights the common characteristics and how the community cohesion in co-housing works in different dimensions such as environment, social, health and affordable terms.

Adding to the insights of the blog, I would like to add few more positive gains of co-housing development in urban context. With all these benefits added up, economic resilience in co-housing is another notable yield for its users creating a self-reliance and distributing equal opportunities to the mixed pool of a larger community. The houses with common retail frontages and shared courtyard spaces for production of goods, farming etc. can be a functional prototype of economic gain in a cohousing development as in Balvonie Green, Inverness. With offices facing front and community courtyards for the occupants in backyard and corners of the plot, they address both economic and social needs of a community without overlapping each other. (Architecture and design scotland, 2017) This provides a working house prototype which could be efficient in certain typologies of co-housing admitting artists or other creative practitioners. It is an opportunity led development with vibrant street interactions to create a distinct urban atmosphere in terms of social cohesion and economic viability.

Another benefit I believe to have in co hosing are spaces designed to accommodate the needs of children. In an urban context children and teenagers are often restricted with freedom of movement. Thus, the spatial syntax is developed without considering the growing generation of a community. In this age of strategy supporting inclusive developments, children should also have equal opportunity and fair treatment towards using the communal streets as others. (Thornton, 2020) This would in turn create a sense of belonging within communal scale from a very younger age and lead them to live a sustainable way of shared future.. A development which fails to address this could create negatively influenced, cultural and economically unstable housing development. (Thornton, 2020) Marmalade lane in Cambridge has beautifully addressed the need of all age groups by liberating the back alleys as communal spaces, where children are prioritised with movable furniture, walkable streets, urban gardens and community hall where they get an opportunity to interact wit all age groups, nature and sense of freedom in movement and understanding the sense of community (Pintos, 2019)

References

Architecture and design scotland, 2017. Housing typology: Adaptables, Edinburgh: ArcDeSco.

Pintos, P., 2019. Marmalade Lane Cohousing Development / Mole Architects. [Online]

Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/918201/marmalade-lane-cohousing-development-mole-architects

[Accessed 19 MAY 2024].

Thornton, A., 2020. In London, children are helping to design the streets. [Online]

Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/12/childfriendly-cities-urban-planning/

[Accessed 19 may 2024].