Public Space in the Perspective of Children’s Right to Play

Introduction

Play is an essential feature of childhood (GEARY, D,2006), and according to Flaubert, the founder of modern preschool theory, ‘play is the highest expression of human development in childhood, for play itself is the expression of freedom within the soul of the child.’ (Friedrich Fröbel ,1826) Play influences children’s cognition, learning, physical development and overall health, and free play is essential to children’s development (Kemple, K.M., Oh, J., Kenney, E. and Smith-Bonahue, T, 2016). It is the duty of urban planners and designers to safeguard children’s reasonable right to play and to create safe, creative and healthy public spaces for play.

However, in recent years, as cities continue to develop, traffic roads and large-scale buildings encroach on most of the city’s space, public space suitable for children’s play is constantly being compressed, and outdoor activity play can only be carried out in a specific small area of public space, public children’s play space with good air quality, low-polluting environments, safe and easy to reach has become more and more precious. Today, many countries and regions around the world are making efforts to create children’s play spaces through policy and social support, with UNICEF releasing the Playful Cities Toolkit in 2022 to better guide the development and construction of international playful cities (Arup.com,2015).

Figure1-The benifits of a playful city (Playful Cities Toolkit,ARUP,2022)

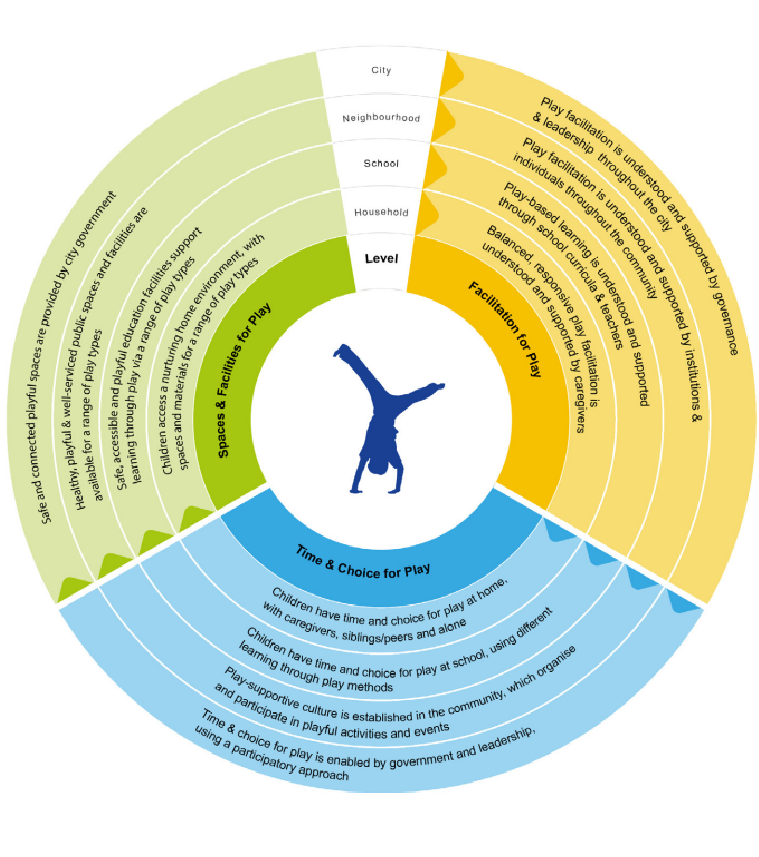

Figure2-The urban play framework (Playful Cities Toolkit, ARUP,2022)

Definition of children’s right to play

The scope of children’s right to play includes the right to age-appropriate play facilities, the right to safety and protection from abuse, the right to non-discrimination, and the right to have their views given due weight. The essence of the right of the child to play is the right to play for the sake of play. The right to play should not only be a means to the fulfilment of a child’s other rights, but also, and above all, a child’s right to choose to play for the sake of playing.

By nature, children want to gather in places where fun is likely to happen, and play in public spaces is a dynamic act. For children, child-friendly public spaces also allow them to learn to explore, express their personalities, maintain socialisation, and gain a sense of identity in a crowd.

Children’s play space

Child-friendly public spaces for play contribute to social life participation. Urban planners and urban designers must create safe and healthy public spaces for free and safe play and interaction. These spaces should be located away from potential hazards to ensure safety and provide a diversity of open space facilities to cater for children’s different interests and activities.

Figure3-Israels Plads(Rasmus Hjortshøj,2017)

Copenhagen, the fairytale city, has been awarded the title of ‘World’s Most Livable City’ and ‘Best Designed City’. In addition, Copenhagen is a very popular city for children, and was one of the first cities to become a ‘child-friendly city’.

Figure4- Experimentarium in Copenhagen(Verena Frei,2019)

Copenhagen’s urban planning and design includes roads, playgrounds and activity spaces specifically designed for children. Respecting, listening to, and taking into account the wishes and feelings of children has been an important part of local government planning since the systematic construction of cities began in the 20th century. Much of Copenhagen has been built from a child’s point of view, and many of the places are designed in a playful way and with a combination of elements that provide a free and safe place for children to move around and for parents to keep an eye on their children. The different functional areas of the square are equipped with barrier-free facilities for prams, strollers and wheelchairs.

Figure5-Playgrounds in Copenhagen( Daniel Rasmussen,no data)

In Nordhavn, Copenhagen’s fast-growing new district, the designers, as participants in urban design, changed the single function of a three-dimensional car park and gave it a new way of use, making it a vibrant public space in the city – Park’n’Play.

Figure6-Green facade and activity landscape on a Parking house(JAJA Architects,2014-2016)

‘PARK’N’PLAY’ is a hybrid structure of car park and playground. It rethinks the mono-functional car park and transforms the usual infrastructural necessities into a public facility. Its location on the roof (24 metres above the ground) provides a recreational area and a view of the horizon, usually reserved for a privileged few. Rather than trying to hide the structure of the parking building, the designers wanted to break up the scale of the façade with an exposed structure that would display its beauty to the people. A series of planting troughs external to the façade creates a rhythmic rhythm that echoes the structure, bringing greenery to every corner while creating a pleasant spatial scale. Two giant staircases are interspersed with steel handrails, which are transformed into swings, climbing frames, bars and other sports and play equipment for all ages on the roof, creating a vibrant public space.(JAJA Architects. 2014 )

Figure7-Green facade and activity landscape on a Parking house(JAJA Architects,2014-2016)

Conclusion

At present, achievements in the field of child-friendly cities and public spaces for children’s play are constantly emerging, including planning manuals, design guidelines, real-life cases and other forms, which can be used for reference in the later stages of design research and implementation, but the occurrence of public spaces for children’s play is subject to multiple influences such as the environment, the economy and the society, and it is more important to adopt targeted guiding measures to address the needs of children’s play in different local cultures, different characteristics of public spaces and different children’s play needs. However, the occurrence of public space for children’s play is subject to multiple influences such as environment, economy and society, and it is necessary to have targeted guidance measures and deepening strategies for different regional cultures, different characteristics of public space and different needs of children’s play.

Reference

- GEARY, D. (2006). Evolutionary developmental psychology: Current status and future directions. Developmental Review, 26(2), pp.113–119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.005.

- Friedrich Fröbel. (1826). Die Menschenerziehung.

- Kemple, K.M., Oh, J., Kenney, E. and Smith-Bonahue, T. (2016). The Power of Outdoor Play and Play in Natural Environments. Childhood Education, [online] 92(6), pp.446–454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2016.1251793.

- Davey, C. and Lundy, L. (2010). Towards Greater Recognition of the Right to Play: An Analysis of Article 31 of the UNCRC. Children & Society, 25(1), pp.3–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00256.x.

- Arup.com. (2015). Playful Cities Toolkit: resources for reclaiming play in cities. [online] Available at: https://www.arup.com/ [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].

- JAJA Architects. (2014). Parking House + Konditaget Lüders. [online] Available at: https://jaja.archi/ [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].

Image reference

- ARUP (2022a). The Benifits of a Playful City. ARUP. Available at: https://www.arup.com/ [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].

- ARUP (2022b). The Urban Play Framework. ARUP. Available at: https://www.arup.com/ [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].

- Hjortshøj, R. (2017). Israels Plads . https://www.rasmushjortshoj.com/. Available at: https://www.visitcopenhagen.com/ [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].

- Frei, V. (2019). Copenhagen – Fun and Food Guide. Freistyle | Foodblog, gesunde Rezepte, Reise und Lifestyle. Available at: https://www.frei-style.com/ [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].

- Rasmussen, D. (n.d.). Playgrounds in Copenhagen. visitcopenhagen. Available at: https://www.visitcopenhagen.com/ [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].

- JAJA Architects (2014). Parking House + Konditaget Lüders. jaja. Available at: https://jaja.archi/ [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].