This blog explores how residential design contributes to reducing crime rates and provides an opportunity to deeply understand the interaction between urban design and community safety. In particular, I realized that the principles of CPTED are essential for mitigating crime and improving the quality of life for residents. These principles focus on creating safe environments in public and residential spaces through key elements such as natural surveillance, physical security, defensible space, and maintenance.

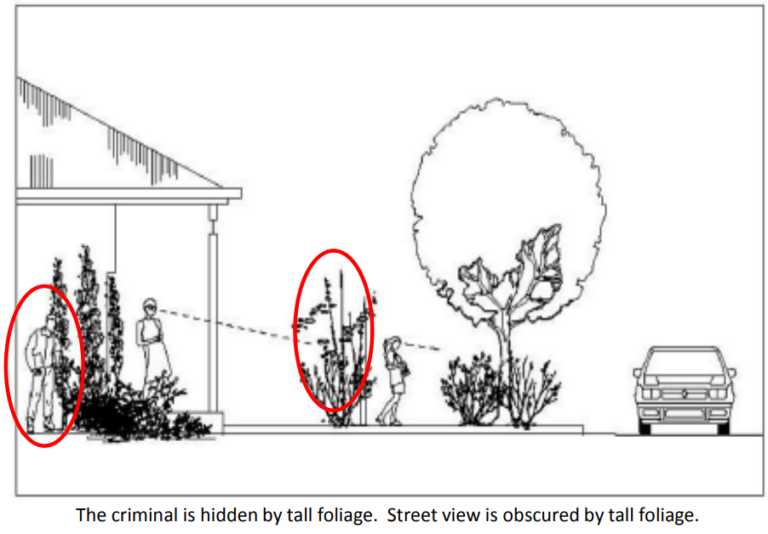

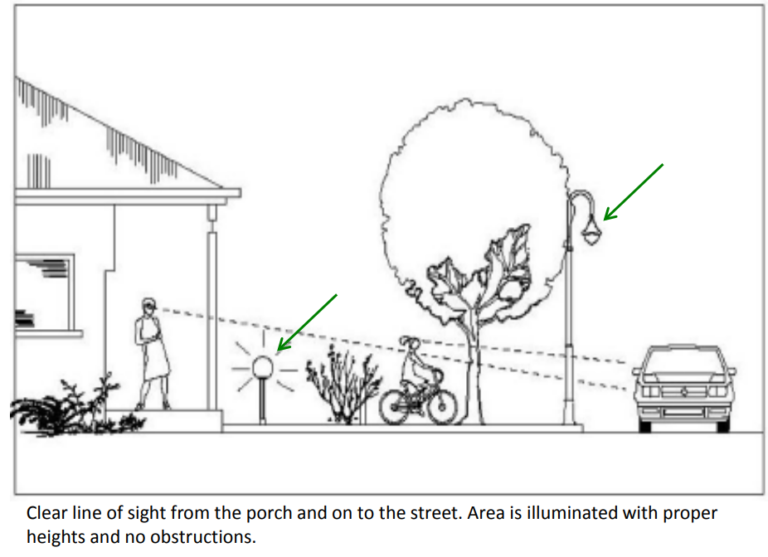

The most striking concept for me was the principle of “eyes on the street,” a key aspect of natural surveillance. This involves designing clear sightlines, adequate lighting, and corner buildings that allow residents to observe public areas naturally, thereby reducing crime. Jacobs (1961) argued that designs promoting natural surveillance strengthen community trust, reducing crime rates. For instance, activating façades on both sides of a corner building can increase street-level activity, enhancing crime prevention and social connectivity

The Broken Window Theory means that the physical environment can easily lead to social disorder and crime. It illustrates that managing the physical environment is not just a matter of appearance but is deeply connected to the psychological sense of safety within the community. According to Cozens et al. (2005), combining well-maintained public spaces with CPTED principles reduces crime and increases residents’ satisfaction with shared environments.

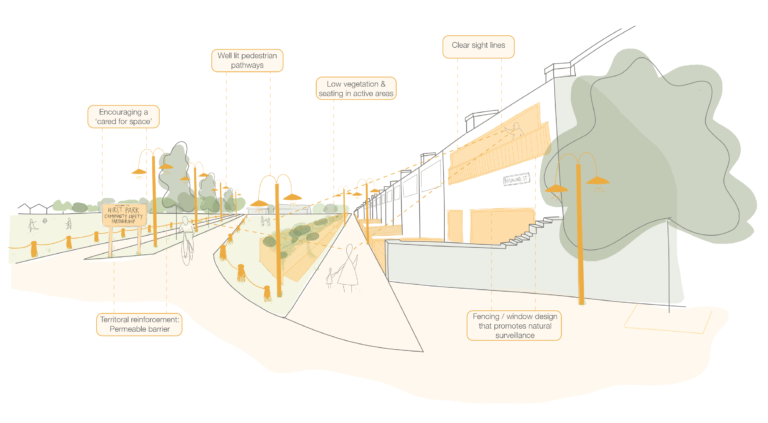

I found the Hirst Park project, as presented through the blogger’s sketch, quite fascinating. The proposal is a successful example of applying these theories to real-world design. This project has significantly contributed to transforming urban residential spaces into safer and more welcoming environments.

Inspired by this article, I investigated successful applications of CPTED principles in South Korea. Since adopting CPTED, Korea’s “Crime Prevention Urban Environment Design Project” has worked to improve psychological safety among residents through better street lighting, murals, and CCTV installations. According to Kang (2020), significant crimes decreased by 64.6%, and resident satisfaction exceeded 70%. A notable example is Seoul’s “Sogeumnaru” in Mapo District, which transformed a once-feared alley into an enjoyable pathway. This project reinforced natural surveillance by turning the space into a vibrant community gathering area, reducing crime reports by up to 22% and fear of crime by 32% (Seoul Design International Forum, n.d.). These examples demonstrate that CPTED principles can work effectively in different cultural contexts.

In conclusion, this article prompted me to reflect on how urban design and community safety can significantly impact the urban environment and residents’ quality of life. I will focus on applying these principles to plan safer and more sustainable urban environments.

List of References

Cozens, P. M., Saville, G., & Hillier, D. (2005). Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): A review and modern bibliography. Property Management, 23(5), 328-356.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Kang, S.-J. (2020). A study of the residents’ satisfaction and effectiveness of CPTED pilot project. Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea, 36(11), 155-162.

Seoul Design International Forum. (n.d.). If the design changes, the crime rate goes down? Available at: https://sdif.org/html/ko/view.php?no=37 [Accessed: 22 December 2024].

This blog explores how residential design contributes to reducing crime rates and provides an opportunity to deeply understand the interaction between urban design and community safety. In particular, I realized that the principles of CPTED are essential for mitigating crime and improving the quality of life for residents. These principles focus on creating safe environments in public and residential spaces through key elements such as natural surveillance, physical security, defensible space, and maintenance.

The most striking concept for me was the principle of “eyes on the street,” a key aspect of natural surveillance. This involves designing clear sightlines, adequate lighting, and corner buildings that allow residents to observe public areas naturally, thereby reducing crime. Jacobs (1961) argued that designs promoting natural surveillance strengthen community trust, reducing crime rates. For instance, activating façades on both sides of a corner building can increase street-level activity, enhancing crime prevention and social connectivity

The Broken Window Theory means that the physical environment can easily lead to social disorder and crime. It illustrates that managing the physical environment is not just a matter of appearance but is deeply connected to the psychological sense of safety within the community. According to Cozens et al. (2005), combining well-maintained public spaces with CPTED principles reduces crime and increases residents’ satisfaction with shared environments.

I found the Hirst Park project, as presented through the blogger’s sketch, quite fascinating. The proposal is a successful example of applying these theories to real-world design. This project has significantly contributed to transforming urban residential spaces into safer and more welcoming environments.

Inspired by this article, I investigated successful applications of CPTED principles in South Korea. Since adopting CPTED, Korea’s “Crime Prevention Urban Environment Design Project” has worked to improve psychological safety among residents through better street lighting, murals, and CCTV installations. According to Kang (2020), significant crimes decreased by 64.6%, and resident satisfaction exceeded 70%. A notable example is Seoul’s “Sogeumnaru” in Mapo District, which transformed a once-feared alley into an enjoyable pathway. This project reinforced natural surveillance by turning the space into a vibrant community gathering area, reducing crime reports by up to 22% and fear of crime by 32% (Seoul Design International Forum, n.d.). These examples demonstrate that CPTED principles can work effectively in different cultural contexts.

In conclusion, this article prompted me to reflect on how urban design and community safety can significantly impact the urban environment and residents’ quality of life. I will focus on applying these principles to plan safer and more sustainable urban environments.

List of References

Cozens, P. M., Saville, G., & Hillier, D. (2005). Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): A review and modern bibliography. Property Management, 23(5), 328-356.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Kang, S.-J. (2020). A study of the residents’ satisfaction and effectiveness of CPTED pilot project. Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea, 36(11), 155-162.

Seoul Design International Forum. (n.d.). If the design changes, the crime rate goes down? Available at: https://sdif.org/html/ko/view.php?no=37 [Accessed: 22 December 2024].

This blog looks into how residential design can help lower crime rates in the UK. It brings together theories, design ideas, and real-life examples, offering solid practical advice. The author explains how design can help prevent crime by discussing the five core principles of CPTED (Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design). They also mention relevant policies and theories, like the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and the Broken Window Theory, which adds to the article’s convincing argument.

The article’s discussion on “Natural Surveillance” is really interesting, especially the part about improving neighbourhood safety by optimising sightlines and boosting activity levels in the design. The author points out that designing buildings with dual active facades at corners improves “passive surveillance” in the neighbourhood. Introducing open, visible green spaces and more transparent community designs helped to effectively reduce crime rates. These designs really enhance safety and help create a feeling of belonging and community involvement among residents, which makes them solutions that are definitely worth promoting.

While the article’s discussion on “Defensible Space” is logically clear, it might be a bit too optimistic about how effective it actually is in practice. Even though clear boundaries such as fences can have a deterrent effect, criminal behaviour often doesn’t limit itself to just having “visual boundaries.” Studies indicate that having high walls or well-defined boundaries might create a “false sense of security,” which could make neighbourhoods feel more isolated and limit chances for natural surveillance, like decreasing pedestrian traffic (Coleman, 1985). So, just depending on clear spatial boundaries might not really lead to effective crime prevention. It’s really important to think about how to bring in socio-economic factors, like encouraging social interaction and trust among neighbours, which the article doesn’t really dive into.

Additionally, the “maintenance design” principle mentioned in the article is also crucial, especially the guidance provided by the Broken Window Theory in reducing crime. However, in practice, maintenance issues often require joint efforts from both the government and residents. For example, in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, community organizations proactively manage neighborhood cleanliness and facility maintenance, not only effectively reducing crime but also strengthening community cohesion (Poorang P, Eric R. P., Emmanuel A., & Janet O, 2019). This suggests that while design is important, the active participation of residents and long-term government investment are also indispensable.

The article does a great job of balancing theory and practice, especially by providing practical and doable suggestions that are based on real-world examples. I hope to learn a lot and really grasp the concept of CPTED. But, looking more closely at how socio-economic factors impact crime prevention and adding more ways for the community to get involved in the design would really strengthen the arguments and make them more meaningful.

Coleman, A. & King’s College . Land Use Research Team (1985) Utopia on trial : vision and reality in planned housing. London: H. Shipman.(Accessed: 6 January 2025).

Poorang, P., EricR.P, F., Emmanuel, A., Janet, O. (2019),Crime prevention in urban spaces through environmental design: A critical UK perspective, [Online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102411 (Accessed: 6 January 2025).

I enjoyed reading this blog, Bea! Such a comprehensive overview of the use of design in lowering crime.

The discussion of theories and evidence is engaging. The Broken Window Theory and theories on defensible space back up your points nicely and strengthen the argument that good urban design can reduce crime rates and improve safety. This passage highlights the importance of maintenance in lowering crime rates. It was particularly interesting for me to do some further reading on the impact of surveillance on the broken window theory. One of the key aspects is the quick mitigation of issues in the area so as to ensure that the area doesn’t develop a perception of neglect (O’Brien, Farrell and Welsh, 2019). For this to properly work, the community needs to identify the person responsible for this. I also found the idea of defensible space very interesting and how this is linked with CPTED as it also bases the idea on natural surveillance but also a territorial concern (Newman, 2008). What I inferred from this is that for these ideas to run alongside each other, it is important to create a sense of ownership in the area so that the community have a sense of ownership and responsibility to the neighbourhood.

The images in your blog were very effective! They clearly represented your ideas and helped you understand the topic quickly, especially with the addition of the circles and arrows.

Your blog gave me a very clear understanding of the principles of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design. It is also interesting to look at how other policies and services support CPTED. For example, the Association of Chief Police Officers commissioned The Design Against Crime Solution Center to evaluate and create strategies to help improve crime prevention services throughout England (Davey, C. and Wootton, A., 2015). Although this resulted in little progress on a national scale, I think it is a very important first step to expand the research on crime prevention through environmental design.

Overall, your blog emphasised the importance of CPTED very well and led to a clear overview supported with examples and visuals. I feel a lot more educated on the topic after reading this!

Reference list

Davey, C. and and Wootton, A (2015) The value of design research in improving crime prevention policy and practice.

Newman, O. (2008) Creating defensible space. Darby, Pa.: Diane.

O’Brien, D.T., Farrell, C. and Welsh, B.C. (2019) ‘Broken (windows) theory: A meta-analysis of the evidence for the pathways from neighborhood disorder to resident health outcomes and behaviors’, Social Science & Medicine, 228(1), pp. 272–292. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.11.015.