In this blog, the author discusses the close relationship between a city’s urban design and its citizens’ well-being, particularly in terms of public health. It traces this link back to historical events and significant personalities, illustrating how urban planning arose as a response to numerous health crises during the Industrial Revolution, such as epidemics and terrible living conditions. The examples range from Leonardo da Vinci’s original “anti-epidemic city” design to the Garden City movement’s emphasis on providing better living environments. It also touches on the modernist architecture movement’s emphasis on better-designed spaces to improve air quality and mental well-being.

In simpler terms, this blog shows how the structure and planning of a city can have a direct impact on the health of its inhabitants. It discusses how cities have changed and been developed throughout history in response to health issues such as disease or pollution. The author, for example, offers ideas from prominent people such as Leonardo da Vinci, who had blueprints for cities that would assist prevent illness spread. It also discusses how cities have changed to provide better living places, such as by including more green space or constructing roadways that are suitable for walking or biking.

To expand on this idea in a more understandable way, let’s think about our own city. Imagine if there were more parks or trees along the streets where we live. This would make the air cleaner, nicer to look at, and better for our health. It would also encourage us to go outside more, maybe ride our bikes or take a walk, which is good for our bodies and minds.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic changed how we think about our cities too. During the pandemic, people found comfort in outdoor spaces like parks, using them as safe places to relax and exercise. This shows how important it is to have accessible green spaces in cities, especially during tough times when people need places to feel calm and less stressed.

The post also mentions that urban design can impact mental health. This means that how our cities are built and organized can affect how we feel emotionally. For instance, having streets with more trees or colorful buildings might make us feel happier or less anxious when we walk around our neighborhood.

In conclusion, the way cities are planned and designed has a big impact on our health and well-being. By creating cities with more green spaces, better streets for walking or cycling, and places that promote social interaction, we can build healthier and happier communities for everyone. It’s not just about buildings and roads; it’s about making spaces that help people live healthier and better lives.

References

01 Barton H, Grant M, Guise R. Shaping Neighbourhoods: for Local Health and Global Sustainability[M]. London: Routledge, 2010.

02 Heard, W. The role of urban design in transforming over-stimulation into resilience, 2016.

03 Roe, J., & Mccay, L. Restorative cities: urban design for mental health and social interaction in the COVID-era, 2021.

Exploring the interdependence between Urban Design and Wellbeing

A city’s quality of life is directly reflected in how sensitive its urban design is to public health. And why? As it would eventually by all means have an impact on the general public during a crisis. Certainly, this claim is supported by a number of historical events. So, let’s start from its origins. (Kuvar, 2023)

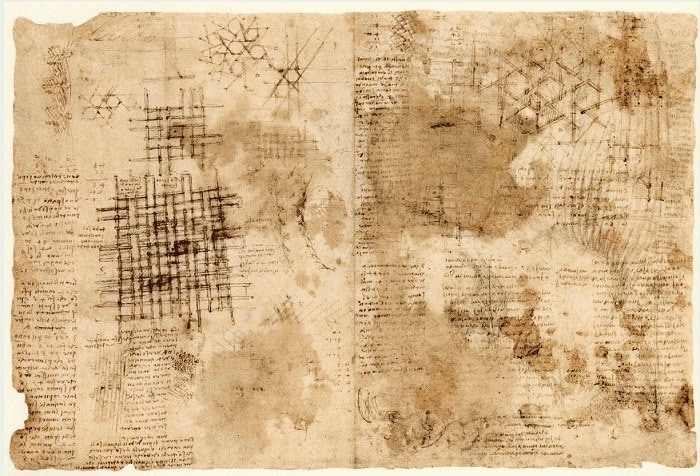

Fig 1: Anti epidemic city- an initial plan by Leonardo Da Vinci Fig 2: Camille Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre, France

The first evidence of urban planning was found from ancient ruins. While living with in the groups and community-oriented development had been the cornerstone of settlements from its beginning the cities evolved as a response to the occurrences of various plagues along the timeline by inspiring several architectural trends in process. (Heard, 2016)

14th– 20th century: A retrospect of Urban planning and public health

Leonardo da Vinci’s “anti-epidemic city” was founded as a remedial measure to the Black Death which halted continent’s urbanization. The findings stated that the disease spread quickly due to street inefficiencies. As a result, he proposed a functional city plan with a closed lower layers. A movement network for products and another for the disposal of wastewater. The three-layered city would serve public life, services, commerce, transportation, and industry. Notably, this initial movement opened possibilities towards rethinking the functionality of public spaces and its impacts on public health.

Fig 3: Black death- An illustration by Pieter Bruegel Figure 4: Lazaretto in Dubrovnik- “An anti-epidemic” model

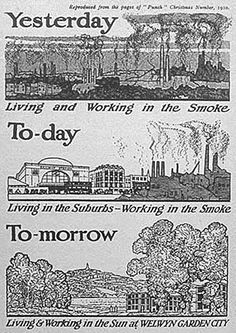

Then, moving on to the 19th century, with the passage of the Public Health Act of 1848 science and urban planning evolved over time. Lately, by combining the advantages of the country and the city, the Garden City movement of 1898 created independent towns.

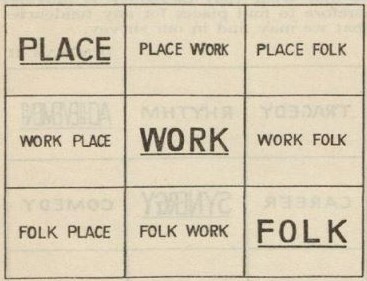

Fig 5: Poster and plan for Welwyn Garden city by Ebenezer Howard Figure 6: Matrix of spaces by Patrick Geddes

At the same time, with Howard’s concepts biologist Patrick Geddes suggested ecological balance and resource renewal in urban planning thereby, improved the quality of life by integrating civic education, geography, and culture into urban planning.

Fig 7: An Illustration by Virginia Bulletin-Urban and countryside Figure 8: Isolation units set up for plague outbreak in Fujiadian

Moving on, the Industrial Revolution by the early 20th century led to rapid urbanization and overpopulation, causing diseases due to poor air quality. Meanwhile, it influenced the emergence of modernism in architecture which focus on light, ventilation, and minimal materials. Especially, Corbusier’s Radiant City, a utopian vision with vertical architecture to improve air, light, and greenery for a better life. (Kuvar, 2023)

21st century- Urban design as a spatial medicine

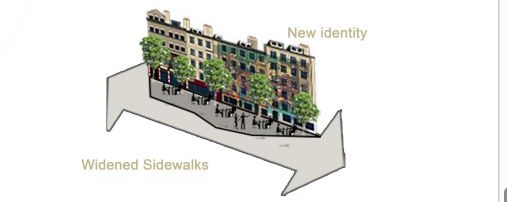

Now, as the cities grew dense, crowded, and chaotic as the aftermath of industrial cities, a direct connection between urban design and mental health is established. From providing open public spaces to accessible streets and to promote better environment for its inhabitants.

Additionally, the unforeseen occurrence of Covid-19 pandemic has created a cultural shift in the utility and functionality of spaces. For instance, recent studies indicate that the use of urban parks and green spaces have dramatically increased as people sought to believe those places as an escape from stress and isolation. Hence, streets transformed themselves to accommodate new ways of life to socialize, exercise, dine or shop at safer distances. (Roe & Mccay, 2021)

Figure 9: Social distancing circles: Domino Park, Newyork city Figure 10: Reusing public spaces to form urban interior, USA.

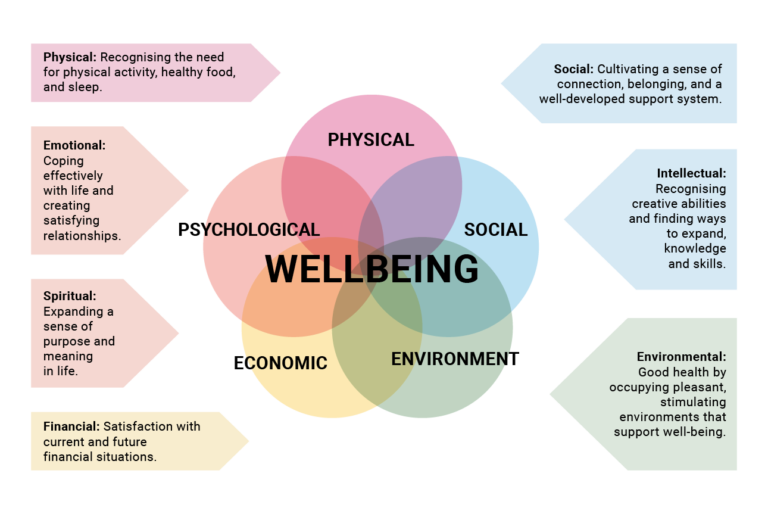

According to World Health Organization- “There is no health without mental health” (Dayal, 2020). Therefore, post pandemic approaches towards the urban design has mental health as an unavoidable aspect in the designing process. Likewise, it also demonstrates how spatial shape, color, nature, water and streets could be utilized to lower the prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression and maintain general well-being.

Figure 12: How Designing a space matter in influencing health and wellbeing by DP Architects

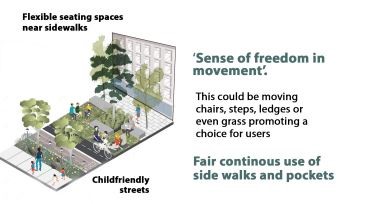

Besides, creating more restorative streets is one way that cities could promote social cohesion and mental health. This include mixed use spaces and extension of activities to the outdoor. Similarly, these approach emphasize the human centered character of streets that promote social well-being. Notably, outlining the ideologies followed by urban sociologists like Jane Jacobs and William Whyte as well as urban planners like Kevin Lynch and Jan Gehl. (Roe & Mccay, 2021)

Urban design as a key to foster Social Interaction and Mental health

Fig 13: Illustrations of Keys to foster social interactions in a urban space by Author.

- Built environment: Mixed use buildings with residences, workplaces, shops and cafes invite people to use public spaces all time of the day.

- Pedestrianized streets: Pedestrianized streets and well-connected cycling paths reciprocate the dependence on automobiles, therefore reduce heart diseases and obesity.

- Legible and well-connected street networks: Indeed makes streets easy to navigate with defined intersections and nodes that generate spontaneous interactions, as well as improves well-being.

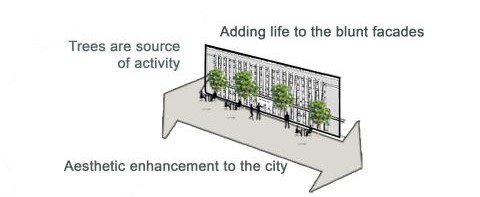

- Adding green palette to the city scape: Street trees could improve aesthetics, induce interactions, cleanse polluted air & buffer noise. Additionally, at the same time could reduce the overall heat accumulated in the space. Therefore, controlling the incidence of stress and depression.

- Additive regeneration: Adding elements of design to the shop fronts and building facades such as public art, murals and green walls which provides the experience of versatility to its users towards the urban space.

Fig 14: General principles for activating a street scape for wellbeing by Author.

In this blog, the author discusses the close relationship between a city’s urban design and its citizens’ well-being, particularly in terms of public health. It traces this link back to historical events and significant personalities, illustrating how urban planning arose as a response to numerous health crises during the Industrial Revolution, such as epidemics and terrible living conditions. The examples range from Leonardo da Vinci’s original “anti-epidemic city” design to the Garden City movement’s emphasis on providing better living environments. It also touches on the modernist architecture movement’s emphasis on better-designed spaces to improve air quality and mental well-being.

In simpler terms, this blog shows how the structure and planning of a city can have a direct impact on the health of its inhabitants. It discusses how cities have changed and been developed throughout history in response to health issues such as disease or pollution. The author, for example, offers ideas from prominent people such as Leonardo da Vinci, who had blueprints for cities that would assist prevent illness spread. It also discusses how cities have changed to provide better living places, such as by including more green space or constructing roadways that are suitable for walking or biking.

To expand on this idea in a more understandable way, let’s think about our own city. Imagine if there were more parks or trees along the streets where we live. This would make the air cleaner, nicer to look at, and better for our health. It would also encourage us to go outside more, maybe ride our bikes or take a walk, which is good for our bodies and minds.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic changed how we think about our cities too. During the pandemic, people found comfort in outdoor spaces like parks, using them as safe places to relax and exercise. This shows how important it is to have accessible green spaces in cities, especially during tough times when people need places to feel calm and less stressed.

The post also mentions that urban design can impact mental health. This means that how our cities are built and organized can affect how we feel emotionally. For instance, having streets with more trees or colorful buildings might make us feel happier or less anxious when we walk around our neighborhood.

In conclusion, the way cities are planned and designed has a big impact on our health and well-being. By creating cities with more green spaces, better streets for walking or cycling, and places that promote social interaction, we can build healthier and happier communities for everyone. It’s not just about buildings and roads; it’s about making spaces that help people live healthier and better lives.

References

01 Barton H, Grant M, Guise R. Shaping Neighbourhoods: for Local Health and Global Sustainability[M]. London: Routledge, 2010.

02 Heard, W. The role of urban design in transforming over-stimulation into resilience, 2016.

03 Roe, J., & Mccay, L. Restorative cities: urban design for mental health and social interaction in the COVID-era, 2021.