________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

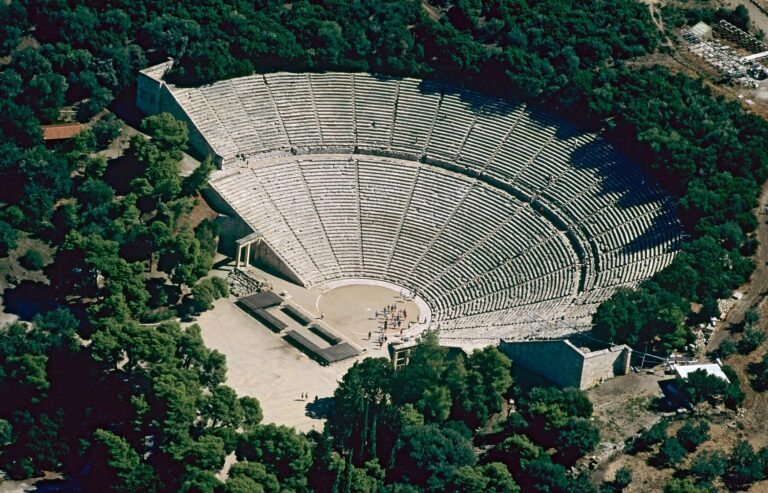

I find this response to the concept of creating healthier cities from the lecture to be well curated and thoroughly elaborated on. You have concisely and creatively identified potential small and cost-effective interventions to create sustainable and healthy portions of cities. I especially appreciate your example of the sanctuary in Epidaurus, depicting a misconceived space whereby healing is the true function. One small idea I had would be to quickly mention the direct connection to the parts of the lecture throughout your post so that it is clear to the reader what exactly you are responding to.

I have two Canadian precedents that came to mind while reading your post. I will begin with the countless pedestrianized streets of Montreal, Canada, referencing your example of Fulton Street. Launched in 2014, the Pedestrian and Shared Streets Implementation Program (PIRPP) aimed at curbing the reliance on automobiles and shifting the focus to pedestrians through, “dynamic public spaces…promoting walkability…participatory planning approach[es]…[and] contributing to each borough’s unique character” (Sokolowski, 2019, p. 52). This program became a huge focus for the city of Montreal to allow for increased outdoor space, thereby enabling human interaction during COVID-19. The project has since been deemed a major success citing flexible and scalable design approaches with social and economic benefits at a vital time, resulting in $12 million worth of funding from the government (Shouse, 2022). The PIRPP can be said to have done well primarily due to its strong over-arching guidelines, yet contextual approaches. Each borough is analysed differently, and community contributions through various member’s proposals are highly valued. Elements such as bike lanes, vegetation, street furniture, lighting, accessibility, decorative elements, patio spaces, raised pavement, and informative signage are tested and implemented to varying degrees (Sokolowski, 2019, p. 53). The result is directly corelated with your points and the principles from the lecture on strategies to create healthier cities through sustainable interventions.

The next example that came to mind is in reference to your precedent, the parklet on Douglas Street. Back when I was in third year of my undergrad, I had the opportunity to lead the design and construction of one of Toronto’s first parklets under the name, ParkletTO. Our design acted as an accessible extension of the sidewalk and created a patio space with ample seating and vegetation for pedestrians to pause and relax amidst the bustling city. Our project acted as the starting point for further parklet interventions implemented in the King Street Transit Pilot. The purpose of this project is like that of the PIRPP, whereby valuable street space in the heart of the city is given back to pedestrians and cyclists alongside sustainable street cars. The project has since been made permanent due to an improved public realm, ease of transit use, and increased spending on local business (Stevens, 2019, p. 4). It further proves your point on how simple, small interventions such as parklets and allotments of pedestrian spaces can go a long way to improving the quality of life in a cost-effective manner.

_____________

References

Shouse, T. Y. (2022, September 27). More pedestrianized streets, please. The McGill Tribune. Retrieved January 5, 2023, from https://www .mcgilltribune.com/opinion/more-pedestrianized-streets-please-270922/

Sokolowski, A. (2019). Retrofitting streets: A documentation of pedestrian-oriented streetscape initiatives in Canada, Halifax, Montreal, Vancouver. eScholarship@McGill. Retrieved January 3, 2023, from https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/papers/f4752n29c

Stevens, B. (2019, July 31). Making Transit King: An Analysis of The King Street Transit Pilot. YorkSpace Home. Retrieved January 5, 2023, from https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/handle/10315/36905

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I find this response to the concept of creating healthier cities from the lecture to be well curated and thoroughly elaborated on. You have concisely and creatively identified potential small and cost-effective interventions to create sustainable and healthy portions of cities. I especially appreciate your example of the sanctuary in Epidaurus, depicting a misconceived space whereby healing is the true function. One small idea I had would be to quickly mention the direct connection to the parts of the lecture throughout your post so that it is clear to the reader what exactly you are responding to.

I have two Canadian precedents that came to mind while reading your post. I will begin with the countless pedestrianized streets of Montreal, Canada, referencing your example of Fulton Street. Launched in 2014, the Pedestrian and Shared Streets Implementation Program (PIRPP) aimed at curbing the reliance on automobiles and shifting the focus to pedestrians through, “dynamic public spaces…promoting walkability…participatory planning approach[es]…[and] contributing to each borough’s unique character” (Sokolowski, 2019, p. 52). This program became a huge focus for the city of Montreal to allow for increased outdoor space, thereby enabling human interaction during COVID-19. The project has since been deemed a major success citing flexible and scalable design approaches with social and economic benefits at a vital time, resulting in $12 million worth of funding from the government (Shouse, 2022). The PIRPP can be said to have done well primarily due to its strong over-arching guidelines, yet contextual approaches. Each borough is analysed differently, and community contributions through various member’s proposals are highly valued. Elements such as bike lanes, vegetation, street furniture, lighting, accessibility, decorative elements, patio spaces, raised pavement, and informative signage are tested and implemented to varying degrees (Sokolowski, 2019, p. 53). The result is directly corelated with your points and the principles from the lecture on strategies to create healthier cities through sustainable interventions.

The next example that came to mind is in reference to your precedent, the parklet on Douglas Street. Back when I was in third year of my undergrad, I had the opportunity to lead the design and construction of one of Toronto’s first parklets under the name, ParkletTO. Our design acted as an accessible extension of the sidewalk and created a patio space with ample seating and vegetation for pedestrians to pause and relax amidst the bustling city. Our project acted as the starting point for further parklet interventions implemented in the King Street Transit Pilot. The purpose of this project is like that of the PIRPP, whereby valuable street space in the heart of the city is given back to pedestrians and cyclists alongside sustainable street cars. The project has since been made permanent due to an improved public realm, ease of transit use, and increased spending on local business (Stevens, 2019, p. 4). It further proves your point on how simple, small interventions such as parklets and allotments of pedestrian spaces can go a long way to improving the quality of life in a cost-effective manner.

_____________

References

Shouse, T. Y. (2022, September 27). More pedestrianized streets, please. The McGill Tribune. Retrieved January 5, 2023, from https://www .mcgilltribune.com/opinion/more-pedestrianized-streets-please-270922/

Sokolowski, A. (2019). Retrofitting streets: A documentation of pedestrian-oriented streetscape initiatives in Canada, Halifax, Montreal, Vancouver. eScholarship@McGill. Retrieved January 3, 2023, from https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/papers/f4752n29c

Stevens, B. (2019, July 31). Making Transit King: An Analysis of The King Street Transit Pilot. YorkSpace Home. Retrieved January 5, 2023, from https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/handle/10315/36905