Greening urban design: A place to live in nature

Rewilding. Photograph by Luke Leung

Greening urban design

As cities around the world grow, it is curial to consider the impact these spaces have on nature and ecosystem. Furthermore, how greenery affect our health and wellbeing. Building greenery can be more inclusive, including among streetscape and urban neighbourhoods. People of all ages and the spaces they experience are dynamic and interconnect, like the communities they represent, inclusion and health equity could represent a moving objective (Stephanie, 2018).

Intergenerational space

In my recent previous blog about age-friendly space and in my design module, Housing Alternative, I have investigated intergenerational living and how spaces in open area, in between and part of the buildings can be catalyst for building social capital and improve public participation and civic trust. Stephanie (2018) further outline four principle; firstly, Context which recongise community context by cultivating knowledge and shared lived experiences that relate to health equity. Secondly, Process which promote the idea of shape public space through participation and social cohesion. Thirdly, Design & Program which foster and design public space for health equity by improving quality and enhancing access and safety. Lastly, Sustain which collectively build social resilience and capacity of local communities.

Daily life urban greening

Urban greening in short, means making urban spaces green! However, more often than not, large green spaces are becoming less common in neighbourhoods or urban developments due to the property privatisation scheme (Colding et al, 2020). Hence, alternative options of greenery are used such as projects like living walls and green roofs are becoming increasingly popular and are found in urban areas. Therefore, benefiting people physical and mental health by boosting morale to those who see it (Riley et at, 2019).

Lesson from Paris and London

Daily access to visible greenery and planning practices still rare even through it is well recongnised in a growing literature. As urban designers, we need to learn from cities that promote greenery instruments. The French policy for example promotes social diversity and the construction of green instruments as part of their intentional green gentrification. This mixes of public social housing in the growing series of urban eco-districts, but also to improve social behavior and opportunity for social interaction (Machline et at, 2020).

Paris Flea Market 1. Photographs by Luke Leung

Paris Flea Market 2 Photograph by Luke Leung

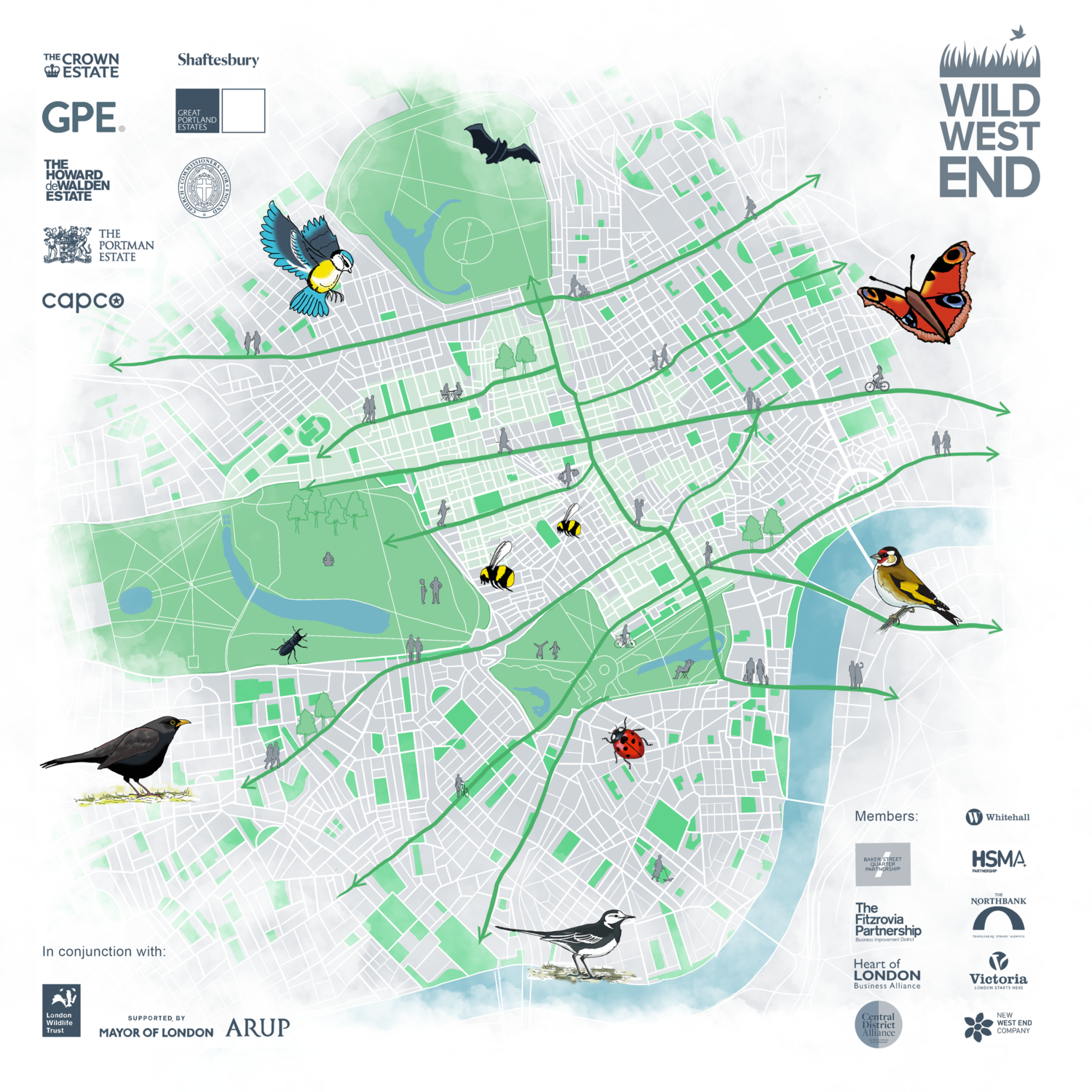

Wild West End London expansion. (Wild West End, 2017)

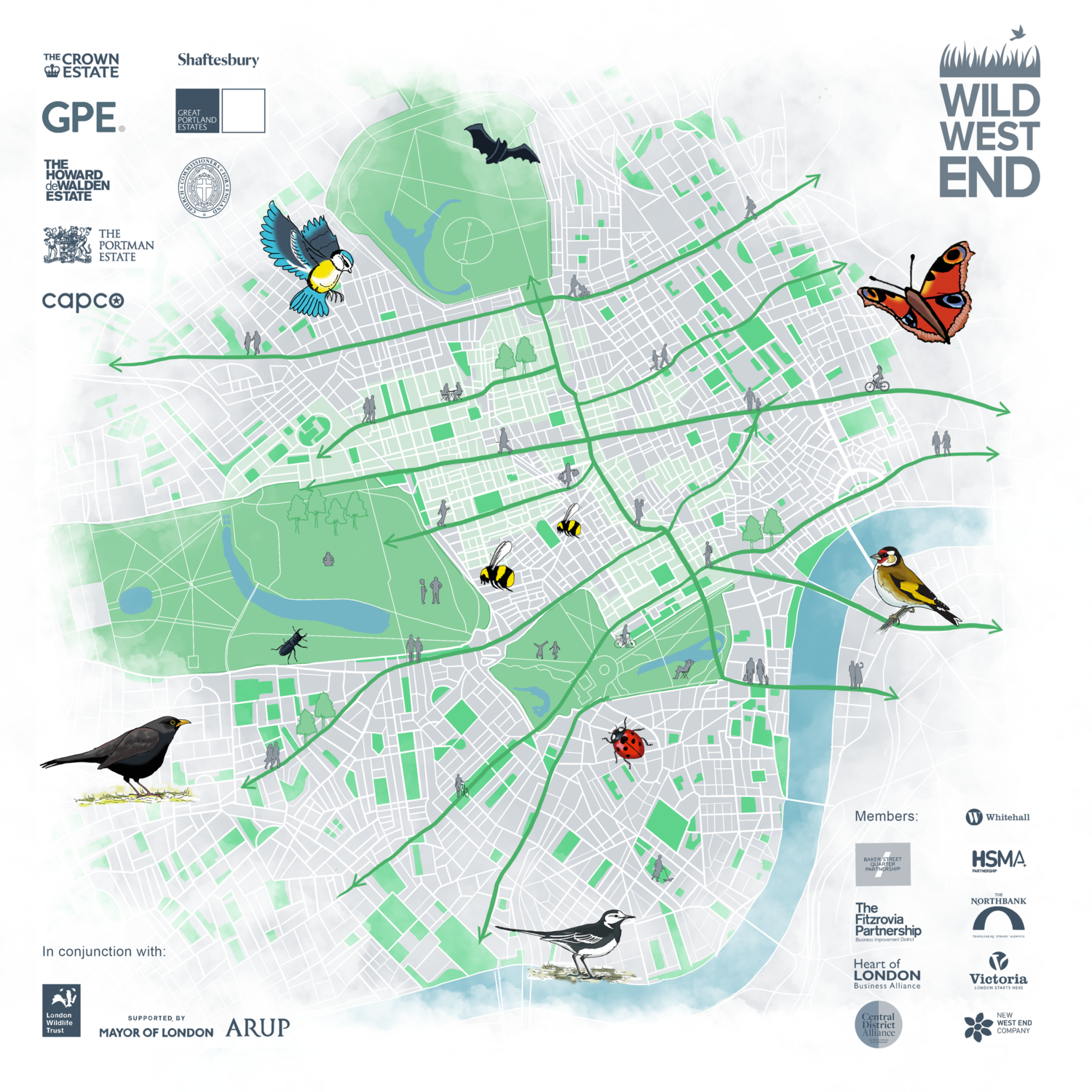

Urban greening also benefits nature and increase biodiversity back into urban environment. Wild West End London (2017) seek to enhance natural ecosystem back into the heart of London, and create greater connections with nature for residents, visitors and workers on their daily commute. Green corridors hope to establish stepping stones between existing areas of surrounding parkland, through a combination of green roofs, living walls, planters, street trees, flower boxes, and rewilding pop-up spaces. This intervention can be seen as human scale design, as well as measurement for wider scale of street greenery masterplan (Ye et at, 2019).

Re-wilding London. (Wild West End, 2017)

In short, the integration of urban greenery and accessibility to green from a human-centred perspective is essential for urban life and it help support social cohesion. The aspect of socio-political landscape need to be improved and better rationalise by planners and designer into practice as example given such as Paris and London. I believe in my recent design module, Housing Alternative urban greenery can be found throughout the former Chandless estate by providing green links are various level, buildings roof, balconies, planters, allotment, street trees and planting area alongside pavements.

Reference:

Colding, J., Gren, A. & Barthel, S. (2020) ‘The Incremental Demise of Urban Green Spaces’. Land. Volume 9, Issue 5. Pp 162.

Machline, E., Pearlmutter, D., Schwartz, M. & Pierre, P. (2020) Green Neighbourhoods and Eco-Gentrification: A Tale of Two Countries. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

Riley, B., Larrard, F., Malécot, V., Dubois-Brugger, I., Lequay, H. & Lecomte, G. (2020) ‘Living concrete: Democratizing living walls’. Science of The Total Environment. Volume 673, Issue 10. Pp. 281-295.

Stephanie, G. (2018) ‘Building more Inclusive, Healthy Places’. Parks & Recreation, Arlington. Volume 53, Issue 9. Pp. 60-62.

Wild West End (2017) Available at: http://www.wildwestend.london/ (Accessed 24th May 2022).

Ye, Y., Richards, D., Lu, Y., Song, X., Zhuang, Y., Zeng, W. & Zhong, T. (2019) Measuring daily accessed street greenery: A human-scale approach for informing better urban planning practices. Landscape and Urban Planning. Volume 191. Pp. 103434.

This is an in-depth discussion of issues that are emerging globally. Thank you, Luke! I agree with the integration of urban greenery and accessibility is essential for urban life. In terms of sustainability, the idea of encouraging green infrastructure is dominated. Green infrastructure refers to standalone and strategically networked environmental features designed for environmental, social and economic benefits. Examples include permeable surfaces, green walls, green roofs and street trees.(Ambrey at al., 2016). However, Much of the current green infrastructure research and guidance focuses on densely populated urban centers. Smaller and rural settlements are often overlooked despite the many benefits that green infrastructure can provide in these settings. According to the Greenbelf Foundation’s study, green infrastructure has considerable value for small settlements, as well as the natural heritage and agricultural systems that form the surrounding countryside. Therefore, It is worth considering creating a green form in a balanced set of the place.

References

– Ambrey, Christopher, et al. “Here’s How Green Infrastructure Can Easily Be Added to the Urban Planning Toolkit.” The Conversation, 2016, theconversation.com/heres-how-green-infrastructure-can-easily-be-added-to-the-urban-planning-toolkit-57277.

– Climate Resilience. “Green Infrastructure Guide for Small Cities, Towns and Rural Communities.” Greenbelt Foundation, 2017, http://www.greenbelt.ca/report_green_infrastructure. Accessed 25 May 2022.

I want to talk about the importance of urban greening.

Benefits of urban greening

1.Combat air and noise pollution.

2.Soaks up rainwater that may otherwise create flooding.

3.Creates a habitat for local wildlife.

4.Offsets carbon emissions in the local area.

5.It has shown to lift morale in the people who see it, with physical and mental health benefits.

6.Calming traffic and lessening urban crime.

As climate change becomes a more prominent issue, architects and city planners alike have been exploring ways to create sustainable urban living.

When something is built, its future is considered as well as its immediate use. By employing urban greening, these buildings contribute more to the environment and the people using it. A living wall or tree-lined path exponentially increases a site’s positive environmental impact. These installations pump vast amounts of oxygen into the air around them, as well as absorbing equally vast amounts of carbon dioxide which would otherwise harm the people around it.

Of course, installations like living walls also help wildlife, with videos of blackbirds living in them reminding us all that we share the world with other creatures, who need a place to live too! Integrating nature into grey urban areas brings beauty and a sense of calm which can be difficult to find in a bustling city.