In this blog the author discusses about technical aspects and the benefits of undertaking Passive house building measures with the example of Prince dale project by Paul David and partners. The write up gives you an insightful explanation of techniques adapted in creating a passive house and how it benefits the users.

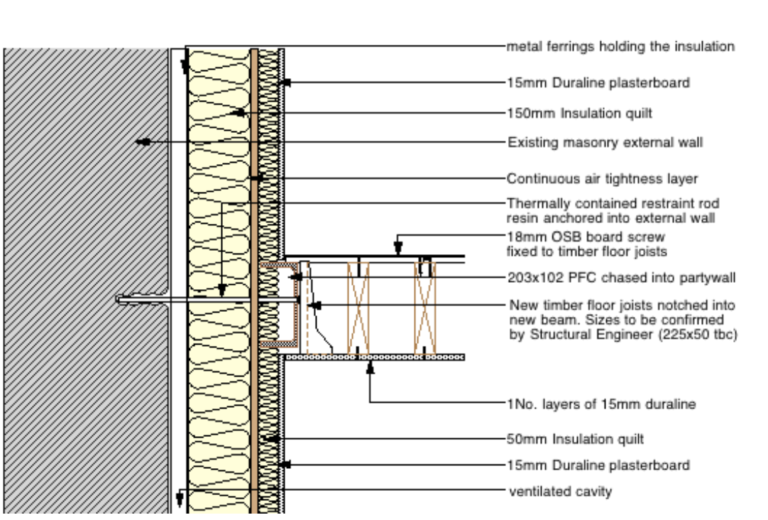

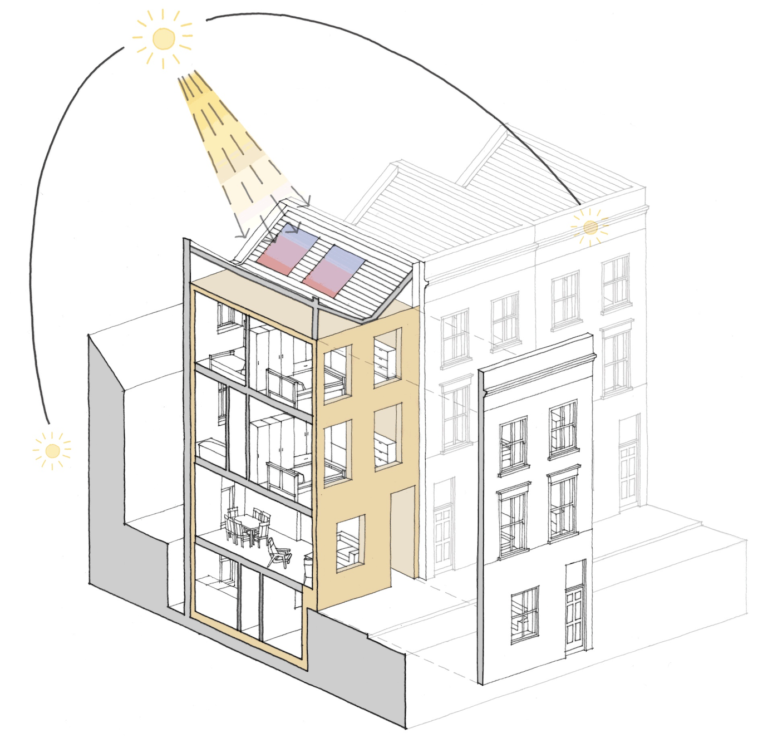

Adding to the insights of the blog, passive building measures have become an inevitable movement in the urban design fabric responding to the fluctuating energy and climate crisis. Also adds to the unhealthy way of living in a house disconnected to the force of nature. Thereby making them irreplaceable element in each new built to improve the quality of life of every stakeholder involved. It’s quite impressive about the prince dale project as they managed to repurpose a Victorian house with minimal additions like re-engineering floors and adding glazed windows to create a huge impact in the energy curve. (Antonelli, 2014)

One of the interesting projects I have gone through with passive techniques in housing was Goldsmith Street, Norwich which applies these parameters in a larger scale and makes it available for all its occupants in an urban context. As one of the largest Passive house schemes in the UK, careful curation was done with its orientation and placement of blocks to attain the efficiency using materials and use of sun. A contrary approach to the technical brilliance of Prince dale Victorian retrofit. According to Andrew Turnbull, Passive Haus are the efficient ways to answer the fuel crisis and adapting towards the climate change. (Passivehaus trust, 2019) To achieve the optimum output, a passive solar scheme was implemented in the streets with terrace housing having windows and habitable rooms make most use of winter sun and avoiding overshadowing by restricting the number of floors. Additionally, the architect implemented vernacular mix of materials like milky coloured cream bricks and black glossy tiles seen most in Norwich’s contextual surroundings to respond and align both the aesthetically and functionally. In order to adapt with insulation standards. Bricks clad walls with 600 mm thickness with deep reveals and sills were used as primary built materials capable of containing the heat and maintain a thermal balance. (Rickaby, 2020)

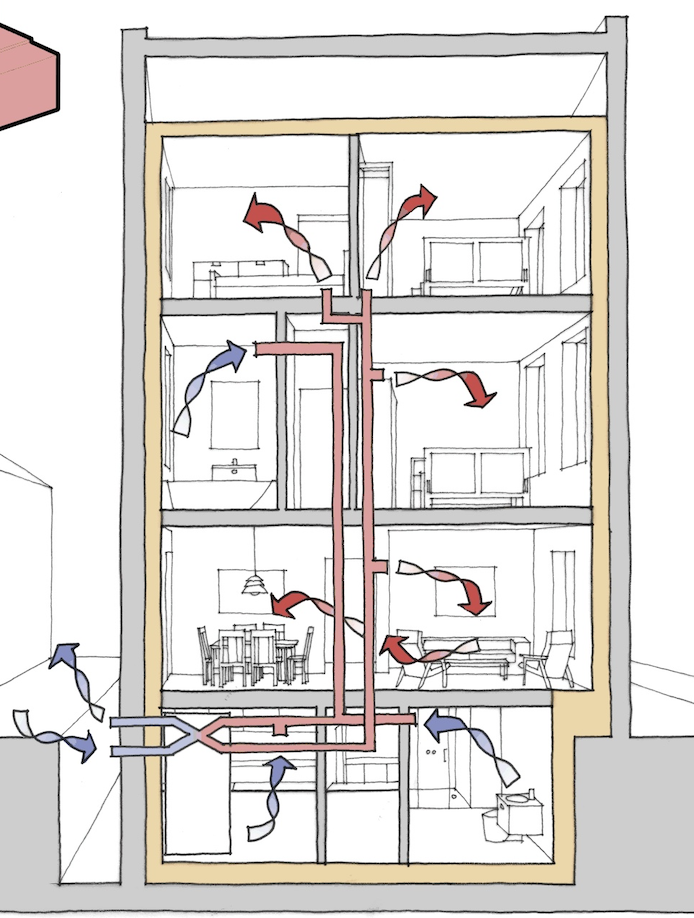

In certain older community housing, Accordia in Cambridge, a combination of solar chimneys and ground earth tunnels like the Princedale project were employed to achieve passive house performance standards. Rather than employing them individually a hybrid installation of both provides optimum results of heating and cooling. More than energy efficiency, Passivhaus recalls the way of living in coherence with nature and its forces.

References

Antonelli, L., 2014. Victorian passive upgrade, Dublin: Passivehouse+sustainable building.

Passivehaus trust, 2019. Goldsmith Street, s.l.: Passivehaus trust.

Rickaby, P., 2020. Stirling Work – The passive social housing scheme that won British architecture’s top award, Dublin: Passivehouse+suatainable building.

In this blog the author discusses about technical aspects and the benefits of undertaking Passive house building measures with the example of Prince dale project by Paul David and partners. The write up gives you an insightful explanation of techniques adapted in creating a passive house and how it benefits the users.

Adding to the insights of the blog, passive building measures have become an inevitable movement in the urban design fabric responding to the fluctuating energy and climate crisis. Also adds to the unhealthy way of living in a house disconnected to the force of nature. Thereby making them irreplaceable element in each new built to improve the quality of life of every stakeholder involved. It’s quite impressive about the prince dale project as they managed to repurpose a Victorian house with minimal additions like re-engineering floors and adding glazed windows to create a huge impact in the energy curve. (Antonelli, 2014)

One of the interesting projects I have gone through with passive techniques in housing was Goldsmith Street, Norwich which applies these parameters in a larger scale and makes it available for all its occupants in an urban context. As one of the largest Passive house schemes in the UK, careful curation was done with its orientation and placement of blocks to attain the efficiency using materials and use of sun. A contrary approach to the technical brilliance of Prince dale Victorian retrofit. According to Andrew Turnbull, Passive Haus are the efficient ways to answer the fuel crisis and adapting towards the climate change. (Passivehaus trust, 2019) To achieve the optimum output, a passive solar scheme was implemented in the streets with terrace housing having windows and habitable rooms make most use of winter sun and avoiding overshadowing by restricting the number of floors. Additionally, the architect implemented vernacular mix of materials like milky coloured cream bricks and black glossy tiles seen most in Norwich’s contextual surroundings to respond and align both the aesthetically and functionally. In order to adapt with insulation standards. Bricks clad walls with 600 mm thickness with deep reveals and sills were used as primary built materials capable of containing the heat and maintain a thermal balance. (Rickaby, 2020)

In certain older community housing, Accordia in Cambridge, a combination of solar chimneys and ground earth tunnels like the Princedale project were employed to achieve passive house performance standards. Rather than employing them individually a hybrid installation of both provides optimum results of heating and cooling. More than energy efficiency, Passivhaus recalls the way of living in coherence with nature and its forces.

References

Antonelli, L., 2014. Victorian passive upgrade, Dublin: Passivehouse+sustainable building.

Passivehaus trust, 2019. Goldsmith Street, s.l.: Passivehaus trust.

Rickaby, P., 2020. Stirling Work – The passive social housing scheme that won British architecture’s top award, Dublin: Passivehouse+suatainable building.