How to deal with loneliness in urban design?

Loneliness is gradually becoming a contemporary urban problem

In 2022, 49.63% of adults (25.99 million people) in the UK reported feeling lonely occasionally, sometimes, often or always [1]. Approximately 7.1% of people in UK (3.83 million) experience chronic loneliness, meaning they feel lonely often or always [2]. This has risen from 6% (3.24 million) in 2020, indicating that there has not been a return to pre-pandemic levels of loneliness [2].

According to “campaign end loneliness”, its definition of loneliness is: a subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when there is a mismatch between the quantity and quality of the social relationships that we have, and those that we want [3].

Analysis of loneliness

Neglected urban spiritual needs

The current focus on public health in urban construction is more on physiological health. Kevin Thwaites believes that the significance of urban spatial design in improving quality of life has been fully recognized, but its soothing effect on the spiritual level is more often seen as a “byproduct” of urban design strategies and has not been fully discussed [4].

Physical infrastructure: Public transport, pedestrian path, city park, parking, public transport, seating, lighting, trash bin, street tree…

Spiritual infrastructure: ? (Elements which need to consider in design.)

Recognize loneliness

Loneliness is a normal psychological state, not a disease.

Everyone has moments of loneliness (such as the elderly who are alone at home, housewives, office workers who live alone, niche enthusiasts, people who eat alone, etc). As an urban designer, what we should do is to care for people from a lonely perspective and face loneliness in a positive way. (Provide people with a place to alleviate loneliness and the possibility of engaging in social activities or enjoying their lonely moments.)

Figure1: What Works Centre for Wellbeing https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/facts-and-statistics/

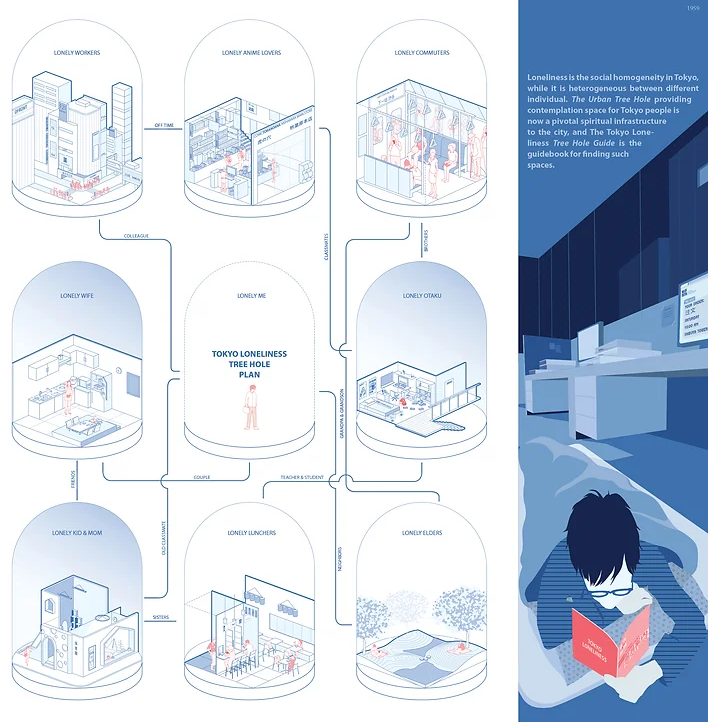

- Design case: Tokyo loneliness tree hole plan

The lonely individuals concern less about the feeling of loneliness than the way loneliness is treated by society and the impact on others by being lonely. As an antidote to loneliness and a strategy for depathologizing it, privacy may be as effective as company for these people[5]. They might prefer to talk to a “tree hole”: a space that can be easily found around, will not respond and disturb others, but provides enclosed shelter and the feeling of safety. Anyone who wants to spend some time alone can go into such space without worrying about the outside world.

Thwaites points out that a restorative urban open space structure is emerging[6]: moves away from the idea of large discrete open areas to more of a web or mesh-like structure that links together a system of smaller spaces, whose quantity and high accessibility in cities have the advantage in tackling mental issues in a timely manner. The “Tokyo Loneliness Tree Hole Plan” proposes such a spiritual infrastructure network of small “urban tree holes” as a systematic maneuver to provide the lonely individuals in Tokyo a chance to get alone with themselves, with the space, and with loneliness.

Figure2: Tokyo loneliness tree hole plan https://www.caigandong.com/urban-mental-desire

Reference

[1] Campaign to End Loneliness with Dr Heather McClelland (2023) Analysis of quarterly report data provided by the ONS from the Opinions and Lifestyle Survey for Jan-Dec 2022 using a representative sample of people aged 16 and over in Great Britain. Note: an average of 2,625 participants engaged with the ONS Opinions during each wave of the Lifestyle Survey over this period.

[2] Campaign to End Loneliness, The State of Loneliness 2023: ONS Data on loneliness in Britain (2023).

[3] Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, A connected society: a strategy for tackling loneliness (2018).

[4] Porta, S., Thwaites, K. & Romice, O. (2007) Urban sustainability through environmental design : approaches to time – people – place responsive urban spaces. London: Taylor & Francis.

[5] Lerner, J. (2019). Escape Hatches. Landscape Architecture Magazine, 12, 228.

[6] Thwaites, K., Helleur, E., & Simkins, I. M. (2005). Restorative Urban Open Space: Exploring the Spatial Configuration of Human Emotional Fulfilment in Urban Open Space. Landscape Research, 30(4), 525-547.