How Urban Design Creates Healthy Neighbourhoods

Health is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” (WHO, 2023). Through urban design, a well-designed neighbourhood can improve the health and wellbeing of its residents through strategic design choices.

Introduction

The impact of neighbourhood design on health is a concept that is being increasingly explored globally. For example, the WHO’s European Healthy Cities Network is an ongoing project aiming to prioritise health and wellbeing in city development at a local and institutional level. They focus on improving urban developments as well as providing education and creating policies to maintain these healthy cities.

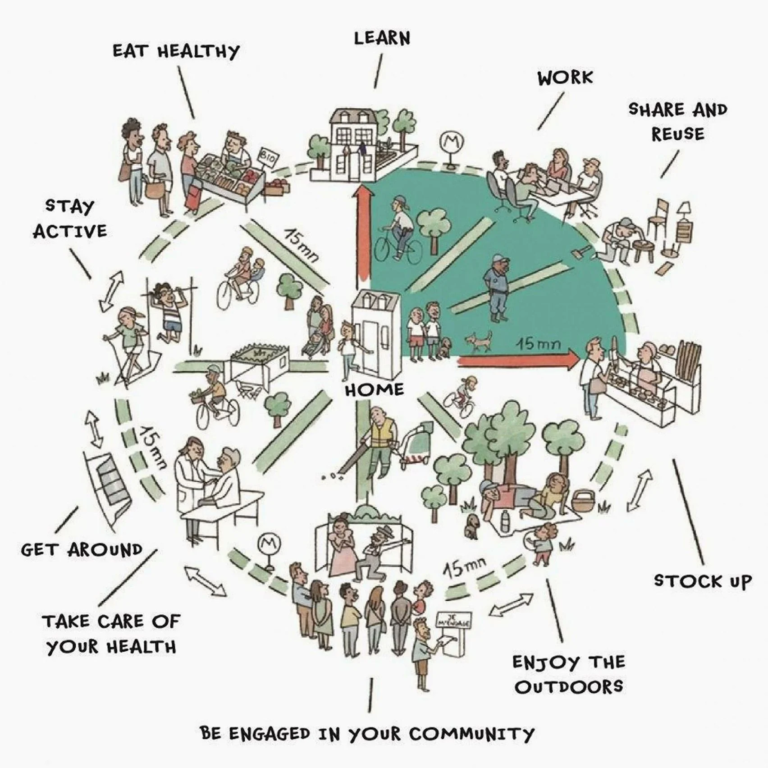

Figure 1 – WHO Healthy Cities Vision (Belfast Healthy Cities, 2017)

Over the last few decades, the rise of the automobile has led to increases in pollution, car-centric infrastructure and the subsequent lack of open or walkable space. The increase in technology has incidentally reduced the amount of daily physical activity, resulting in a more sedentary lifestyle. This leads to many health issues such as increased obesity and type 2 diabetes (Woessner, 2021).

Sustainability and the environment are now at the forefront of many developments today. Seen through increasing green spaces and providing more sustainable transport alternatives, these solutions also have positive health impacts.

Green and Blue Spaces

Green spaces are defined as areas mainly covered by vegetation. This includes parks, gardens, and woodlands. Blue spaces include bodies of water in urban areas, such as coastal margins of cities, rivers, canals, and ponds. Overall, many studies show that having these spaces within urban areas benefit both physical and mental health.

Some physical health benefits include reducing air pollution and urban heat. Street trees are particularly effective at reducing air pollution and temperatures compared to non-green areas. Studies show that tree-covered areas can reduce temperatures by 1°C which can help reduce the heat island effect caused by urban infrastructure (Dadvand and Nieuwenhuijsen, 2019).

The provision of green and blue space can also indirectly influence physical activity. Parks, trails and other outdoor areas support a wide range of activities which can benefit physical health, such as walking and cycling. Making sure that these areas remain well-maintained and attractive ensures their continued use.

Figure 2 – Primrose Hill, London (Valiev, 2021)

Green spaces have positive impacts on mental health. Studies quoted by Dadvand and Nieuwenhuijsen (2019, p. 416) show that increased contact with green space is associated with a lower risk of depression and anxiety. Kondo et al (2018) also present studies that prove exposure to natural urban settings can help reduce stress. They stated that exposure to nature improved cognitive functions such as attention and improved mood, as well as providing opportunities for socialising.

Walkable Neighbourhoods

The conditions that make a place walkable include being compact, traversable, safe, and physically enticing. The resulting outcomes of walkability include creating sociable spaces, sustainable transport options, and exercise (Forsyth, 2015). Thus, for urban designers, the interventions that lead to creating walkable neighbourhoods must be supported by relevant infrastructure.

The concept of 15-minute cities aims to reduce car dependency by keeping basic services within a 15-minute walking or cycling radius. By creating compact, mixed-use spaces, this can reduce congestion and pollution and increase green space and physical activity (Moreno, 2021). This provides the opportunity for socialising and providing public transport for better connectivity outside neighbourhoods. A study mentioned by Ige-Eledbede (2020) states that better access to public transport and amenities can increase walking and physical activity.

Figure 3 – 15-minute cities (Dezeen, 2023)

Other interventions such as traffic calming measures and increased lighting help improve safety. Furthermore, adding benches, greenery, and playgrounds makes these areas more attractive to spend time in.

Socio-economic influence

Socio-economic status can influence health and wellbeing. Generally, higher socio-economic groups tend to live in greener neighbourhoods and have better health status. Lower socio-economic groups face poorer quality green space, housing, and amenities (Dadvand and Nieuwenhuijse, 2019). This inequality has negative impacts on the health and wellbeing of these residents, such as greater risks of cardiovascular disease. Examples from the European Environment Agency (2023) show how planning for better access to green space, more accessible spaces and community gardens create better social inclusion and reduce inequality.

Conclusion

Urban design interventions play a part towards the overall health of a community. By ensuring suitable developments in all types of areas are benefitting the needs of the residents, this creates a better environment for residents to live in.

References:

Dadvand, P. and Nieuwenhuijsen, M. (2019), ‘Green Space and Health’, in Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Khreis, H. Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning, Springer, pp. 409 – 424

Forsyth, A. (2015), ‘What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design’, Urban Design International, 20, pp. 274 – 292. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2015.22

Ige-Elegbede, J. et al (2022), ‘Designing healthier neighbourhoods: a systematic review of the impact of the neighbourhood design on health and wellbeing’, Cities & Health, 6(5), pp. 1004-1019, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1799173

Kondo, M. C. et al. (2018), ‘Urban Green Space and Its Impact on Human Health’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3), 445. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030445

Moreno, C. et al. (2021), ‘Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities’, Smart Cities, 4, 93-111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4010006

Woessner, M. et al. (2021), ‘The Evolution of Technology and Physical Inactivity: The Good, the Bad, and the Way Forward’, Frontiers in Public Health, 9, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.655491

World Health Organisation (2023), Constitution. Available at: https://www.who.int/about/accountability/governance/constitution (Accessed: 30 December 2023)

Image references:

Belfast Healthy Cities (2017), World Health Organization European Healthy Cities Network. Availabe at: https://belfasthealthycities.com/world-health-organization-european-healthy-cities-network

Dezeen (2023), A simple guide to 15-minute cities. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2023/10/16/15-minute-city-guide/

Valiev, T. (2021), London skyline, view from Primrose Hill. Available at: https://unsplash.com/photos/a-group-of-people-sitting-on-top-of-a-lush-green-field-WkyfavX8uc8