Landscape urbanism dates back to 2050, when it is estimated that 70% of the world’s urban population will live in cities, rather than the 2% of the world’s territory and 55% of the global population. Landscape urbanism must be transformed in this more urgent context.

Most people can foresee a dire end if cities continue to grow in this way. Responding to these crises is complex and difficult because they are global in nature and in the context of rapid value-added economic development.

In the face of these crises, various reflections and debates have emerged in the 20th and 21st centuries, the more important of which are: one is which type of building or layout is more environmentally friendly, compact or decentralised? Another is the debate about the role of the designer in the urbanisation process. This is because in practice the real power to make larger decisions is often in the hands of governments or investors, and the intervention of designers is limited.

The theory of landscape urbanism and the discipline of urban design are in some cases closely related, as Charles Waldheim states in his Landscape Urbanism: “It is perhaps inevitable that urban design has now shifted from its former intimate relationship with architecture to accept landscape architecture as a more rational and relevant discipline”. Landscape urbanism is the product of a mixture of disciplines.

However, it is not only inevitable that any new ideas and theories will once again be influenced, but it is also a necessary part of the development of human culture and science. The concept of landscape urbanism has been discussed by the landscape design community for over a decade. As with many emerging ideas, the concept is the result of joint thinking by landscape architecture academics and practitioners. The term ‘landscape urbanism’ was coined by Charles Waldheim, the current head of the Department of Landscape Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Together with his colleagues Alex Krieger and Mohsen Mostafavi and James corner of the University of Pennsylvania, he worked on the formation of the concept. In contrast to Europe, in the United States there is an ongoing and profound debate about the urbanisation of the landscape in which the lines of ‘who agrees and who disagrees’ are drawn from time to time.

Landscape Urbanism

When designing, all designers should consider the present and future of the object being designed, especially in urban planning.

Today, urban planning projects must be planned in detail for 5, 10, or 20 years. Who can really “predict” the future and plan everything accurately? The problem with the future is that it is different. We can think differently, and the future will always come as a surprise.

Landscape Urbanism

Let us consider our cities and the changing factors related to where we live, the environment, and how we live in them.

We are using the following as reference points.

1. Society

2. Technology

3. Environment

4. Economics

5. Politics

Let us return to Landscape Urbanism, by 2050; it is estimated that 70% of the world’s urban population (10 billion people) will be living in cities (footprint locations) instead of the current 2% of the world’s land that accounts for 55% of the global population. Landscape Urbanism needs to be transformed in this more urgent context, and the theory of landscape urbanism and the discipline of urban design are closely related in some cases. As Charles Waldheim’s Landscape Urbanism puts it, “the ongoing and perhaps inevitable shift of urban design from its long-standing intimacy with architecture to an embrace of landscape architecture as its most logical, kindred discipline.”

“… anticipates that by increasing compression in dense urban and suburban areas, municipal development of recreational areas will be urgently needed ” (Krieger and Saunders 2009).

(Geoff Whitten,2021)

From the mid-19s onwards, many cities around the world have launched urban strategies that present various ‘visions of the future world, with a variety of buildings, streets surrounded by greenery, creating a sustainable and ‘good living’ future, attracting high levels of mobility, and a ‘good living’ future. A “good life” future that attracts a highly mobile and talented workforce and makes them stay.

Why is there so much green space in the vision of the future?

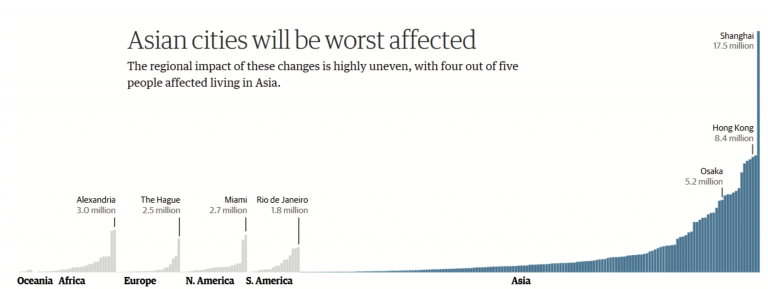

Severe weather events and sea-level rise threaten any country or region of the world, causing countless losses of people and property. This has led all countries and regions to commit to creating a sustainable, safe and beautiful city.

Of course, these problems (severe weather events and sea-level rise) did not only emerge in the 20th century but also in the 19th century when various countries and regions proposed different solutions: Patrick Geddes – “city region,” Ebeneezer Howard – Garden Cities. Garden Cities. The emergence of Ian L. McHarg brought ecological planning fully into urban planning.

Ian L. McHarg was one of the most influential people in the environmental movement. He brought environmental issues into the wider public consciousness and applied ecological planning methods to landscape design, urban planning, and public policy.

Peter Rowe’s contextualism school is more concerned with urban form than architectural language. Deconstructivism proposes horizontal vegetation planes and landscapes as critical elements of the urban order.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Landscape Urbanism became widely used in all parts of the city and began to investigate more deeply the various aspects of the landscape city: Charles Waldheim – The landscape urbanism reader, Moshen Mostafavi – Landscape urbanism and Ecological urbanism. urbanism and Ecological urbanism.

(Newcastle -Helix,2015)

Landscape Urbanism is the product of a mixture of professions, positive use of waste materials, and an emphasis on function rather than the mere appearance of [the] landscape.

10 Aspects of Landscape Urbanism

1. landscape urbanism rejects the dichotomy between city and landscape

2. landscape replaces architecture as an essential component of the city. Corollary: Landscape urbanism involves the collapse or radical realignment of traditional disciplinary boundaries.

3. Landscape urbanism involves a massive scale in time and space.

4. Landscape urbanism prepares the site for action and the performance stage.

5. Landscape urbanism is less concerned with how things look and more with what they do.

6. Landscape urbanism sees the landscape as machinic.

7. landscape urbanism makes the invisible visible

8. landscape urbanism embraces ecology and complexity

9. landscape urbanism encourages hybridity between natural and engineered systems

10. landscape urbanism recognizes the remedial possibilities inherent in the natural world

Landscape Urbanism SUMMARY and CONCLUSIONS.

1. Landscape Urbanism always needs to evolve, and all people can contribute to it.

2.Landscape Urbanism should not be difficult to understand.

3. The Green Infrastructure (Landscape Institute) approach is an excellent place to start, linking the idea of Landscape Urbanism to the urban design process.

4. Landscape Urbanism needs to be adapted to place more emphasis and consideration on the people themselves (the social and political realities of the city), as well as seeking a new aesthetic to create and maintain a sense of place (including heritage issues), and all in the context of a continuing global shift in power.

Reference

Geoff, W., 2021. Landscape Urbanism Lecture. 1st ed. [ebook] Newcastle: Newcastle University. Available at: <https://www.ncl.ac.uk/> [Accessed 27 November 2021].

Patrick, G., 2021. Cities in evolution: an introduction to the town planning movement and to the study of civics: Geddes, Patrick, Sir, 1854-1932: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet Archive. [online] Internet Archive. Available at: <https://archive.org/details/citiesinevolutio00gedduoft> [Accessed 27 November 2021].

Ebenezer, H., 1985. Garden cities of tomorrow. Eastbourne: Attic Books.

McHarg, Ian L. Design with Nature. 25th Anniversary ed. New York: J. Wiley, 1994. Print.

Frampton, Kenneth. Modern Architecture: A Critical History. Fifth ed. 2020. Print. World of Art.

Rowe, Peter G. Making a Middle Landscape. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 1991. Print.

Koolhaas, Rem., Bruce. Mau, Jennifer. Sigler, Hans. Werlemann, and Office for Metropolitan Architecture. Small, Medium, Large, Extra-large: Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rem Koolhaas, and Bruce Mau. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y.: Monacelli, 1998. Print.

Waldheim, Charles. The Landscape Urbanism Reader. New York: Princeton Architectural, 2006. Print.

Mostafavi, Mohsen., Gareth. Doherty, and Harvard University. Graduate School of Design. Ecological Urbanism. Rev ed. Zürich: Harvard, Mass.: Lars Müller; Harvard U, Graduate School of Design, 2016. Print.

The Core. 2015. The Core – Newcastle Helix. [online] Available at: <https://www.thecorenewcastle.co.uk/> [Accessed 10 January 2022].

Landscape urbanism dates back to 2050, when it is estimated that 70% of the world’s urban population will live in cities, rather than the 2% of the world’s territory and 55% of the global population. Landscape urbanism must be transformed in this more urgent context.

Most people can foresee a dire end if cities continue to grow in this way. Responding to these crises is complex and difficult because they are global in nature and in the context of rapid value-added economic development.

In the face of these crises, various reflections and debates have emerged in the 20th and 21st centuries, the more important of which are: one is which type of building or layout is more environmentally friendly, compact or decentralised? Another is the debate about the role of the designer in the urbanisation process. This is because in practice the real power to make larger decisions is often in the hands of governments or investors, and the intervention of designers is limited.

The theory of landscape urbanism and the discipline of urban design are in some cases closely related, as Charles Waldheim states in his Landscape Urbanism: “It is perhaps inevitable that urban design has now shifted from its former intimate relationship with architecture to accept landscape architecture as a more rational and relevant discipline”. Landscape urbanism is the product of a mixture of disciplines.

However, it is not only inevitable that any new ideas and theories will once again be influenced, but it is also a necessary part of the development of human culture and science. The concept of landscape urbanism has been discussed by the landscape design community for over a decade. As with many emerging ideas, the concept is the result of joint thinking by landscape architecture academics and practitioners. The term ‘landscape urbanism’ was coined by Charles Waldheim, the current head of the Department of Landscape Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Together with his colleagues Alex Krieger and Mohsen Mostafavi and James corner of the University of Pennsylvania, he worked on the formation of the concept. In contrast to Europe, in the United States there is an ongoing and profound debate about the urbanisation of the landscape in which the lines of ‘who agrees and who disagrees’ are drawn from time to time.

Landscape Urbanism was first proposed by the urban designer Charles Waldheim. He advocated that architecture and infrastructure be seen as a continuation of the landscape or an uplift of the surface. In addition to being a green space or natural space, the landscape should also be continuous support for the urban fabric. FOR EXAMPLE, the NY The High Line, designed by James Corner, is a successful example of landscape urbanism. This project is a brownfield use of a viaduct and provides a model for design worldwide, transforming derelict spaces into vibrant urban public spaces and chronic corridors.

Secondly, the landscape architect’s initial job is to design a park and design the overall urban form. So I think landscape urbanism is again based on that. It calls for designers to think in a more macro, open, and economical way about how the landscape profession influences urban landscape development. The landscape as a medium for the city should not be thought of as a small garden or an individual in the city. Landscape urbanism defines the landscape well. The landscape is the continuous topography and the supporting structure of the city that ties it together. As you say, landscape urbanism is the active use of waste materials and emphasises function rather than just the landscape’s appearance. To agree with you. Landscape urbanism should not be understood from the perspective of the landscape as a starting point. The features of landscape architecture should then be mere tools in the concept of landscape urbanism. Landscape urbanism is not necessarily about the suitability and sustainability of the habitat by doing landscape sightlines. Its focus is all about urbanism and the solution to the problems of urbanisation.