Make Space More Welcoming to Adolescent Girls

Dilemmas for girls in public spaces

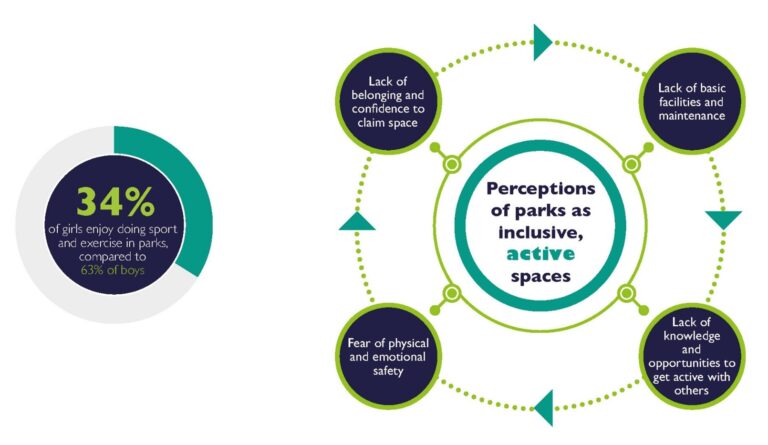

According to studies about outdoor play in Belgium, boys make much more use of outdoor play spaces than girls. The gap between boys’ and girls’ playing outside is particularly significant in the user group between the age of ten to eleven. This is the age at which their autonomy develops further (Kind und Samleving 2020). Additionally, a research project by White Research Lab in 2016 revealed that, enjoying sports and exercise in parks, 80 percent of users were boys because girls had ten times more feelings of insecurity (Zimm 2016). A programme from England in 2022, Making Space for Girls, also showed that teenage girls felt excluded in children’s space, such as playgrounds, and adults’ ones, such as high streets. It articulates that there are gendered and aged barriers for adolescent girls to experience their own life in public spaces. The lack of inclusive spaces for teen girls could lead to less outdoor activities and social interactions, which hinder their mental health and wellbeing development (King and Feldman 2022). To encourage teenage girls to be more active and ensure their access to enjoyment and freedom in public spaces, the physical design of parks and public spaces could be more adolescent-girl-friendly.

Figure 1: Girls’ Perceptions and Use of Parks and Green Spaces (Yorkshire Sport Foundation, 2022)

Why parks and public spaces are undesirable for girls?

Current provision for adolescents consists of facilities provided in open space, including three main types, skate parks, multi-use game areas and pump track. Girls feel that these facilities are created for boys’ sports and activities, which stop them using parks. survey in York showed that 90 percent of girl skateboarders had feeling of unsafety due to the predominance of boys and hassle from them. Additionally, skateparks lowered girls’ daily use of parks for exercise (Paechter et al. 2023). In terms of multi-use game areas, which are also preempted by boys, the physical design deters teenage girls. The fenced space with a single exit makes girls feel trapped. Moreover, teenage girls are conditioned by social norms where they are not treated children or mature women. These factors cause that adolescent girls perceive parks and other public spaces which are unsafe and provide no facilities for them. The specific inequality needs to be addressed by design aligned with girls’ interests (Walker and Clark 2023).

Figure 2: MUGA with a single entrance (AXO Leisure)

What teenage girls really want from parks?

Girls are looking for fun and social options and less interested in competitive and organized sports. However, majority of spaces offer opportunities for sports for adolescents, rather than physical activity for all teenagers. Work in UK found that teenage girls had a desire to spend time in parks through play and activity. They required play facilities that are appropriate in their age. In relation to the requirement, several specific installations have been demonstrated to make parks more attractive to girls:

- Seatings and sheltered places providing opportunities for face-to-face conversations

- Swings allowing social interactions

- Outdoor gyms encouraging physical activity

- Spaces consisting of smaller areas that facilitate activities for variety of age groups

- Walking looped paths increasing activity levels

- Toilets and changing facilities (Make Space for Girls 2021).

Figure 3: An installation for a temporary spark providing physical outdoor experience with room for face-to-face conversation that many teen girls are looking for (Horner 2014)

How to create spaces more inviting for girls?

It is essential that design and planning outcomes properly address the needs of teenage girls. The fundamental principle is to enhance safety and sociability in play space and park landscape designs. Various physical interventions can be implemented to tackle the issue of teenage girls being marginalized in public spaces, ensuring their equal right to play. Firstly, park areas designed with sufficient clear exits can create openness for safety. Consequently, dense vegetation and fenced courts may contribute to a sense of unsafety. Secondly, instead of providing a single large open space, creating multiple smaller areas within it facilitates the sharing of the space among different groups. When a singular large area is built, it is usually occupied by the most dominant group. Additionally, smaller parks with adequate passive surveillance and relatively fewer middle-to-edge areas improve girls’ sense of security. Thirdly, providing sociable play spaces with features, such as seats, shelters and swings, can increase the active use of outdoor spaces in a fun way. Girls are enthusiastic about playful and flexible equipment which creates seating space for them and allows them to have face-to-face interactions. Finally, mixed-use play spaces and park landscapes designed with gender sensitivity can provide more equitable opportunities for diverse users and meet a wider range of needs. Given public spaces generally dominated by men, gender-sensitive mixed-use designs can be used to establish priorities when building physical spaces. With appropriate interventions, exclusionary places can be transformed into inclusive spaces for girls, in fact, for all people (Barker et al. 2022).

References

Barker, A., Holmes, G., Alam, R., Cape, D. L., Osei, A. S. and Warrington, B. S. 2022. What Makes a Park Feel Safe or Unsafe? The views of women, girls and professionals in West Yorkshire. Available at: https://greenflagaward.org/media/2407/parks-report-final-7122022.pdf [Accessed: 01 April 2023].

Kind und Samleving. 2020. Girls and public space. Available at: https://indd.adobe.com/view/c203db90-24b7-40b4-b289-fd7c9292f22f [Accessed: 01 April 2023].

King, J. and Feldma, O. 2022. Are girls being designed out of public spaces?

Available at: https://www.lse.ac.uk/research/research-for-the-world/society/are-girls-being-designed-out-of-public-spaces [Accessed: 29 March 2023].

Make Space for Girls. 2021. Girls and skateparks: A guide for councils, developers, and funders. Available at: https://www.makespaceforgirls.co.uk/resources/girls-and-skateparks-a-guide-for-councils-developers-and-funders [Accessed: 30 March 2023].

Paechter, C., Stoodley, L., Keenan, M. and Lawton, C. 2023. What’s it like to be a girl skateboarder? Identity, participation and exclusion for young women in skateboarding spaces and communities. Women’s Studies International Forum 96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2023.102675.

Walker, S. and Clark, I. 2023. Make space for girls research report 2023. Available at: https://assets.websitefiles.com/6398afa2ae5518732f04f791/63f60a5a2a28c570b35ce1b5_Make%20Space%20for%20Girls%20-%20Research%20Draft.pdf [Accessed: 01 April 2023].

Zimm, M. 2016. Girls’ room in public space-planning for equity with girl’s perspective. In Besters, M. et al. 2019. Our city? Countering exclusion in public space [Adobe Digital Editions version]. Amsterdam: STIPO. Available at: https://stipo.myshopify.com/products/order-our-city-countering-exclusion-in-public-space [Accessed: 01 April 2023].

Figures

AXO Leisure, MUGA with a single entrance, digital image, accessed 1 April 2023, <https://www.axoleisure.co.uk/single-post/bespoke-heavy-duty-muga>.

Horner, J 2014, An installation for a temporary spark providing physical outdoor experience with room for face-to-face conversation that many teen girls are looking for, digital image, Höweler + Yoon Architecture, accessed 1 April 2023, <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-05-28/we-need-more-public-space-for-teen-girls>.

Yorkshire Sport Foundation 2022, Girls’ Perceptions and Use of Parks and Green Spaces, Yorkshire Sport Foundation, Leeds, accessed 01 April 2023, <https://www.makespaceforgirls.co.uk/resources/make-space-for-us>.