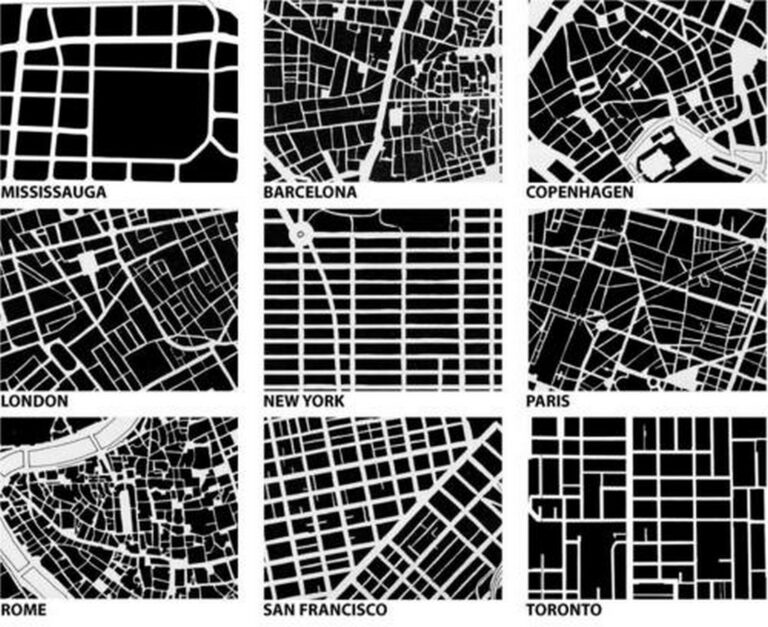

As the built environment develops, guidelines in the form of design principles are important (RTPI, 2019). This is in the pursuit of coherent, congruent, and purposeful places. As you said, they ‘demonstrate how cities can be designed, built and rebuilt to create sustainable, humane human habitats.’

Interestingly, the nine planning principles you have set out correspond to Parker et al’s (2017) list of the top 25 priorities for improving high streets in the UK. With these similarities clear, our collective goal of coherence and congruence in design seems more attainable. Providing that these guidelines are taken for what they are – guidelines – they help designers hone their creativity toward a common goal. However, there is an important distinction to be made here. Design principles are different from design codes.

As a definition, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2021) state that ‘a design code is a set of simple, concise, illustrated design requirements that are visual and numerical wherever possible to provide specific, detailed parameters for the physical development of a site or area’. This implies a more rigid guide. Although, I still believe codes, as well as principles, should be taken as guidance. Thus, both sponsoring more congruent and coherent landscapes.

An example of this congruence can be seen in our Ouseburn project, namely ‘The Use of Design Codes’. Here, we were tasked to critically engage with and respond to the Ouseburn design code. As a result, many of our final models worked well when placed adjacent to each other on the wider site context model. For sure, this could be an example of the design codes ‘working’. However, we need to be realistic too. It could also be a result of similar teaching methods and studio influence. Nonetheless, a revelation worth looking at.

All in all, it is promising that your 9 planning principles correspond with other design principles in current literature. Providing these are taken for what they are – guidelines – these help massively in creating high quality, coherent and purpose-built places.

References:

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2021) National Model Design Code. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/957205/National_Model_Design_Code.pdf (Accessed: 24th May 2022).

Parker, C. et al (2017) Improving the vitality and viability of the UK High Street by 2020: Identifying priorities and a framework for action. Journal of Place Management and Development. DOI:10.1108/JPMD-03-2017-0032

RTPI (2019) Planning and Design Quality; Creating Places Where We Want to Live, Work and Spend Time. Available at: https://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/1990/planninganddesignquality2019.pdf (Accessed: 24th May 2022).

As the built environment develops, guidelines in the form of design principles are important (RTPI, 2019). This is in the pursuit of coherent, congruent, and purposeful places. As you said, they ‘demonstrate how cities can be designed, built and rebuilt to create sustainable, humane human habitats.’

Interestingly, the nine planning principles you have set out correspond to Parker et al’s (2017) list of the top 25 priorities for improving high streets in the UK. With these similarities clear, our collective goal of coherence and congruence in design seems more attainable. Providing that these guidelines are taken for what they are – guidelines – they help designers hone their creativity toward a common goal. However, there is an important distinction to be made here. Design principles are different from design codes.

As a definition, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2021) state that ‘a design code is a set of simple, concise, illustrated design requirements that are visual and numerical wherever possible to provide specific, detailed parameters for the physical development of a site or area’. This implies a more rigid guide. Although, I still believe codes, as well as principles, should be taken as guidance. Thus, both sponsoring more congruent and coherent landscapes.

An example of this congruence can be seen in our Ouseburn project, namely ‘The Use of Design Codes’. Here, we were tasked to critically engage with and respond to the Ouseburn design code. As a result, many of our final models worked well when placed adjacent to each other on the wider site context model. For sure, this could be an example of the design codes ‘working’. However, we need to be realistic too. It could also be a result of similar teaching methods and studio influence. Nonetheless, a revelation worth looking at.

All in all, it is promising that your 9 planning principles correspond with other design principles in current literature. Providing these are taken for what they are – guidelines – these help massively in creating high quality, coherent and purpose-built places.

References:

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2021) National Model Design Code. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/957205/National_Model_Design_Code.pdf (Accessed: 24th May 2022).

Parker, C. et al (2017) Improving the vitality and viability of the UK High Street by 2020: Identifying priorities and a framework for action. Journal of Place Management and Development. DOI:10.1108/JPMD-03-2017-0032

RTPI (2019) Planning and Design Quality; Creating Places Where We Want to Live, Work and Spend Time. Available at: https://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/1990/planninganddesignquality2019.pdf (Accessed: 24th May 2022).