Reflection on Practice: Community engagement

A New Kind of Suburbia by Metropolitan Workshop has attempted to explore and challenge the growing suburbia through their practice based research. Dhruv (2021) led this project, aimed to enhance our understanding with the ever expansion of the suburbs. Noticeably, the challenges faced by existing and new suburban resident in the changing market condition, allows the Metropolitan Workshop to create a design-led response to the typical housing development process, in order to encapsulate the policy makers, client and design practices to increase the design value.

Understanding the process

First, the standard procedure in modern day housing development process needs to be understand and reflected upon. The main contributor to the UK land and housing development opportunities are developers and volume housebuilders. They primarily speculate plots of land as whether or not worth investing in. As Bentley (1999) argues, the construct that scopes the ‘opportunity space’ meaning can private developers & volume housebuilders meets their budget constraints and produce a profitable product. If deem worthwhile, then they will proceed with numerous policy requirements starting with National policy, and Local plan & guidance. The following diagram illustrate the full diagram:

Typical process for developments

Why community engagement is essential

Barrier faced with typical engagement with community

White et al (2020) argues that in the typical housing development world, community engagement and consultation typically occur too late in the planning process. White continues to argue that engagement within local communities about new housing development tends to be ‘top-down’ and poorly implemented. The approach of community participation is often not well understood, however design practices/ organisation that reflect on co-producing and community planning has often led to better design value. Moreover, the pandemic has made it evident that a cohesive and sustainable community are the key factors that forms the true sense of community and identity (London, 2020).

Tiers of communities involvement

Community planning in essence could help empower people in the community to solve community segregation problems. Governments rarely have sufficient means to resolve all the problems in an area, whereas local people can bring additional resources which are often essential if their needs are to be met (Wates, 2014). Furthermore, involvement can benefit to better decisions, more appropriate and inclusive results, and be fulfilling to the public’s demand.

Community led project

Source: Metropolitan Workshop. (2021) Aerial view of the proposed development.

An example of a community led program is the Oakfield Village (Nationwide, 2021). Metropolitan Workshop was involved in this engagement as part of their practice research. This project was initiated by Nationwide and their development partner to create a mix tenure and sustainable homes on a previous brownfield site.

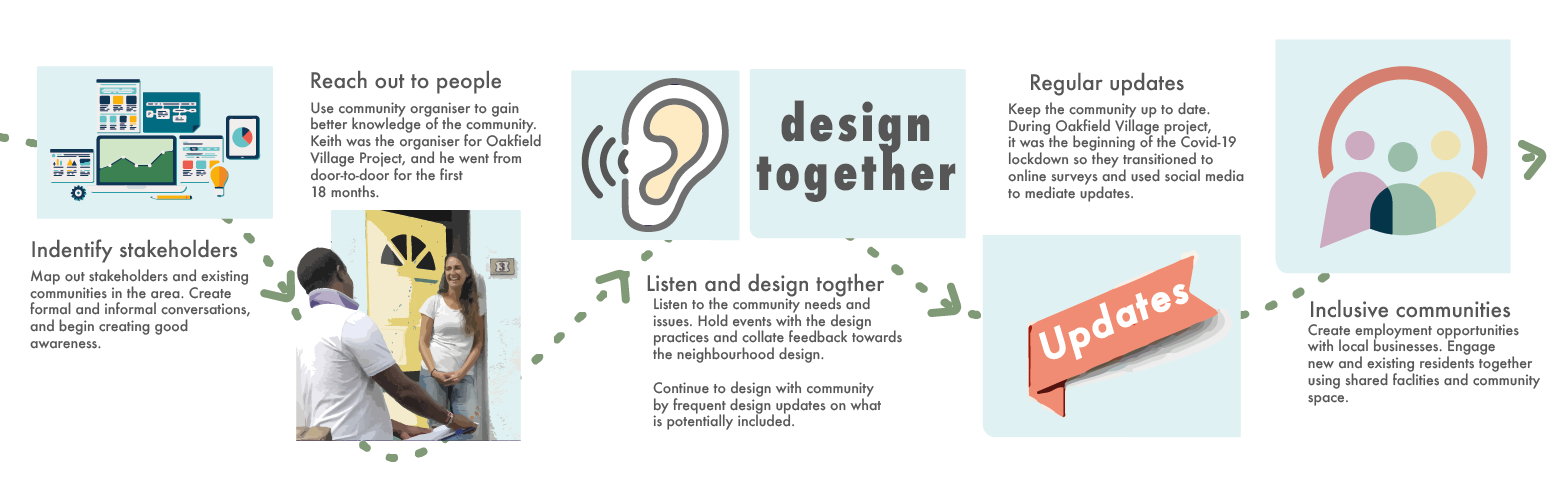

Oakfield Village stories of engagement started by identifying the stakeholders, then reached out to the communities. The thoughts and issues surrounding the site were heard before evolving into a design together. Updates of the progress were shared to the communities, which helped create a sense of community involvement and was integral to achieving goals. Additionally, the engagement process from Oakfield Village started from the beginning with the community organisers’ going door-to-door.

Example of community led development: Oakfield Village adaptation.

Community development strategy allows practices and development partners to profile objectives; addressing the social and physical needs. By involving the community in all stages, directly or indirectly, the involvement will enhance the project (Hawtin et al, 1994). Through public consultation, workshops, and events it can purposefully create an end result that extends beyond the red site line. Application line will further translate to transportation and connection to the wider communities, ultimately leaving a legacy where the future of the community can continue to thrive.

In conclusion, the notion of community engagement development vastly improves on the current solution as well as creating inclusion for new suburban residents. The social and physical connection built upon the engagement reduces the effect of gentrification as members feels valued and improves their way of life. Likewise, although the concept of community involvement can broad and inherently fuzzy, members from each party need to take the initiative to create this realistic and feasible utopia.

Reference:

Bentley, I. (1999) Urban transformations – Power People and Urban Design, Routledge, London.

Dhruv, S. (2021) A New Kind of Suburbia. Available at: https://metwork.co.uk/research/a-new-kind-of-suburbia/ (Accessed: 5th January 2022).

Hawtin, M., Hughes, G., And Percy-Smith, J. (1994) Community profiling: Auditing social needs. Open University Press, Buckingham.

London, F. (2020) Healthy Place Making: Wellbeing through Urban Design. RIBA, London.

Metropolitan Workshop. (2021) Aerial view of the proposed development. Available at: https://metwork.co.uk/work/oakfield-village/ (Accessed 5th January 2022).

Nationwide Building Society (2021) The Oakfield Story: A thoughtful approach to community engagement. Available at: https://www.nationwide.co.uk/-/assets/nationwidecouk/documents/about/building-a-better-society/the-oakfield-story.pdf?rev=ddbf4cb9f8944868982be10a1ce033d4 (Accessed 5th January 2022).

Wates, N. (2014) The Community Planning Handbook. Second edition. Routledge, London.

White. J., Kenny, T., Samuel, F., Foye, C., James, Gareth. And Serin, B. (2020) Delivering design value: The housing design quality conundrum. Available at: https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/12506_CaCHE_Delivering_Design_Main_Report_IA-1.pdf (Accessed: 5th January 2022).