The topic surrounding gender mainstreaming in urban design is a fascinating subject and one that has a growing recognition, particularity in academic institutions where societal norms are readily challenged. William Whyte was pioneering in his 1970s ‘The Street Life Project’ for having a conscious observation of women in urban space, whilst also actively listening and learning from women within his research team. This was due to the fact Whyte believed that women were tougher critics of what defines a well design urban space, as they are more sensitive to annoyances (Whyte, 2011, p. 511).

This inclusion and engagement with women within the design process is key in creating an inclusive environment. Whilst this concept of inclusion was revolutionary in the 1970s, it has now grown in popularity and understanding across the urban design world and as such, initiatives such as ‘Make Space for Girls’ and the ‘Women Friendly Cities Challenge’ are able to aid in spreading awareness of the issues facing women today. ‘Make Space for Girls’ have a key understanding that ‘the single best way to create a park which works for teenage girls is to talk to them’.

A key case study for addressing gender mainstreaming is Frauen-Werk-Stadt (Women-Work-City), which was the first gender-sensitive housing project in Vienna. This development was designed exclusively by women and centred around women’s’ lived experiences. The goals of the development were to make housework and care work easier, encourage a sense of community and create comfortable and safe living environments (Women Friendly Cities Challenge, 2021).

The design team adopted the concept of ‘Eyes on the Street’ by Jane Jacobs, who advocated for safety on the streets in the form of high-density inner city living, which she argued benefitted from natural neighbourhood surveillance (Jacobs, 2011). Not only did this concept adopt high-density but crucially it also advocated for well-defined neighbourhoods and narrow crowed multiuse streets. In order to achieve this, Jacobs proposed the use of clear definitions between public and private spaces, multi-use facilities on the street to maintain activity throughout all times of the day, and buildings orientated towards the street to increase the natural surveillance (Jacobs, 2011).

However, it should be noted that whilst the Frauen-Werk-Stadt was a pioneering development, it is still crucial to reflect on some of the lessons learnt during the process. The Women Friendly Cities Challenge explained that whilst there was a women led design and planning team ‘some of the women on the project team were inexperienced or did not hold feminist views’ which meant the design was not realised to its full potential (2021). I believe this links back to my previous comments surrounding the growing acceptance of the topic of gender mainstreaming and the need for not only engagement but also awareness to successfully realise an inclusive urban environment.

REFERENCES

Jacobs, Jane, The uses of sidewalk: safety, in LeGates, R.T. & Stout, F. (2011) The city reader. 5th ed. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, pp.105-109.

Make Space for Girls, (n.d.) Better Design Suggestions for Parks, Available at: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://assets.website-files.com/63989e164f27a3461de801f1/63ef5c46f1e5b87ee653000e_Better-Ideas.pdf [accessed 28/03/24]

Whyte, William, The design of spaces, in LeGates, R.T. & Stout, F. (2011) The city reader. 5th ed. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, pp.510-517.

Women Friendly Cities Challenge, (2021) Gender-sensitive Housing in Vienna – Frauen-Werk-Stadt, Available at: https://womenfriendlycitieschallenge.org/wise-practices/gender-sensitive-housing-in-vienna-frauen-werk-stadt-women-work-city/ [accessed 28/03/24]

Figure 1. Women and man in the station(

Figure 1. Women and man in the station(

The topic surrounding gender mainstreaming in urban design is a fascinating subject and one that has a growing recognition, particularity in academic institutions where societal norms are readily challenged. William Whyte was pioneering in his 1970s ‘The Street Life Project’ for having a conscious observation of women in urban space, whilst also actively listening and learning from women within his research team. This was due to the fact Whyte believed that women were tougher critics of what defines a well design urban space, as they are more sensitive to annoyances (Whyte, 2011, p. 511).

This inclusion and engagement with women within the design process is key in creating an inclusive environment. Whilst this concept of inclusion was revolutionary in the 1970s, it has now grown in popularity and understanding across the urban design world and as such, initiatives such as ‘Make Space for Girls’ and the ‘Women Friendly Cities Challenge’ are able to aid in spreading awareness of the issues facing women today. ‘Make Space for Girls’ have a key understanding that ‘the single best way to create a park which works for teenage girls is to talk to them’.

A key case study for addressing gender mainstreaming is Frauen-Werk-Stadt (Women-Work-City), which was the first gender-sensitive housing project in Vienna. This development was designed exclusively by women and centred around women’s’ lived experiences. The goals of the development were to make housework and care work easier, encourage a sense of community and create comfortable and safe living environments (Women Friendly Cities Challenge, 2021).

The design team adopted the concept of ‘Eyes on the Street’ by Jane Jacobs, who advocated for safety on the streets in the form of high-density inner city living, which she argued benefitted from natural neighbourhood surveillance (Jacobs, 2011). Not only did this concept adopt high-density but crucially it also advocated for well-defined neighbourhoods and narrow crowed multiuse streets. In order to achieve this, Jacobs proposed the use of clear definitions between public and private spaces, multi-use facilities on the street to maintain activity throughout all times of the day, and buildings orientated towards the street to increase the natural surveillance (Jacobs, 2011).

However, it should be noted that whilst the Frauen-Werk-Stadt was a pioneering development, it is still crucial to reflect on some of the lessons learnt during the process. The Women Friendly Cities Challenge explained that whilst there was a women led design and planning team ‘some of the women on the project team were inexperienced or did not hold feminist views’ which meant the design was not realised to its full potential (2021). I believe this links back to my previous comments surrounding the growing acceptance of the topic of gender mainstreaming and the need for not only engagement but also awareness to successfully realise an inclusive urban environment.

REFERENCES

Jacobs, Jane, The uses of sidewalk: safety, in LeGates, R.T. & Stout, F. (2011) The city reader. 5th ed. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, pp.105-109.

Make Space for Girls, (n.d.) Better Design Suggestions for Parks, Available at: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://assets.website-files.com/63989e164f27a3461de801f1/63ef5c46f1e5b87ee653000e_Better-Ideas.pdf [accessed 28/03/24]

Whyte, William, The design of spaces, in LeGates, R.T. & Stout, F. (2011) The city reader. 5th ed. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, pp.510-517.

Women Friendly Cities Challenge, (2021) Gender-sensitive Housing in Vienna – Frauen-Werk-Stadt, Available at: https://womenfriendlycitieschallenge.org/wise-practices/gender-sensitive-housing-in-vienna-frauen-werk-stadt-women-work-city/ [accessed 28/03/24]

Thank you for sharing your insights on gender mainstreaming in urban design. Your comments really shine a light on the importance of this topic and how it has evolved, especially in the context of today’s increasing calls for inclusion and diversity in society.

As you point out, William H. Whyte demonstrated in his research in the 1970s the importance of listening to women to improve the design of urban spaces. The idea he discovered through The Street Life Project, that women are harsher critics of urban space because they are more sensitive to inconveniences, remains relevant. This approach to focusing on women’s needs was not only revolutionary at the time, it has now become a core principle of many urban design projects.

The various practical projects you mentioned are also very inspiring. For example, the Frauen-Werk-Stadt project. Not only does the project emphasize women’s leadership in design and planning, it also adopts Jane Jacobs’ “Eyes on the Street” philosophy, which emphasizes making streets safer through natural community surveillance. This design concept, combined with multi-functional uses and a clear division of public and private spaces, does provide strong support for the creation of a safe and comfortable urban environment. Nonetheless, you also mentioned some challenges encountered during the project, particularly the inexperience of team members or the lack of a feminist perspective. This reminds us that in the process of promoting gender mainstreaming, not only women’s participation is needed, but they also need to have corresponding knowledge and awareness to ensure the realization of design goals.

Overall, your comments highlight the importance of incorporating a gender perspective in urban design and call for continued increased attention and understanding of this topic. I completely agree with you that it is only through continued engagement and awareness raising that we can truly achieve an inclusive and equitable urban environment.

References

Whyte, William, The design of spaces, in LeGates, R.T. & Stout, F. (2011) The city reader. 5th ed. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, pp.510-517.

Jacobs, Jane, The uses of sidewalk: safety, in LeGates, R.T. & Stout, F. (2011) The city reader. 5th ed. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, pp.105-109.

Gender-sensitive housing in Vienna – frauen-werk-stadt (women-work-city) (2022) Women Friendly Cities Challenge. Available at: https://womenfriendlycitieschallenge.org/wise-practices/gender-sensitive-housing-in-vienna-frauen-werk-stadt-women-work-city/ (Accessed: 17 May 2024).

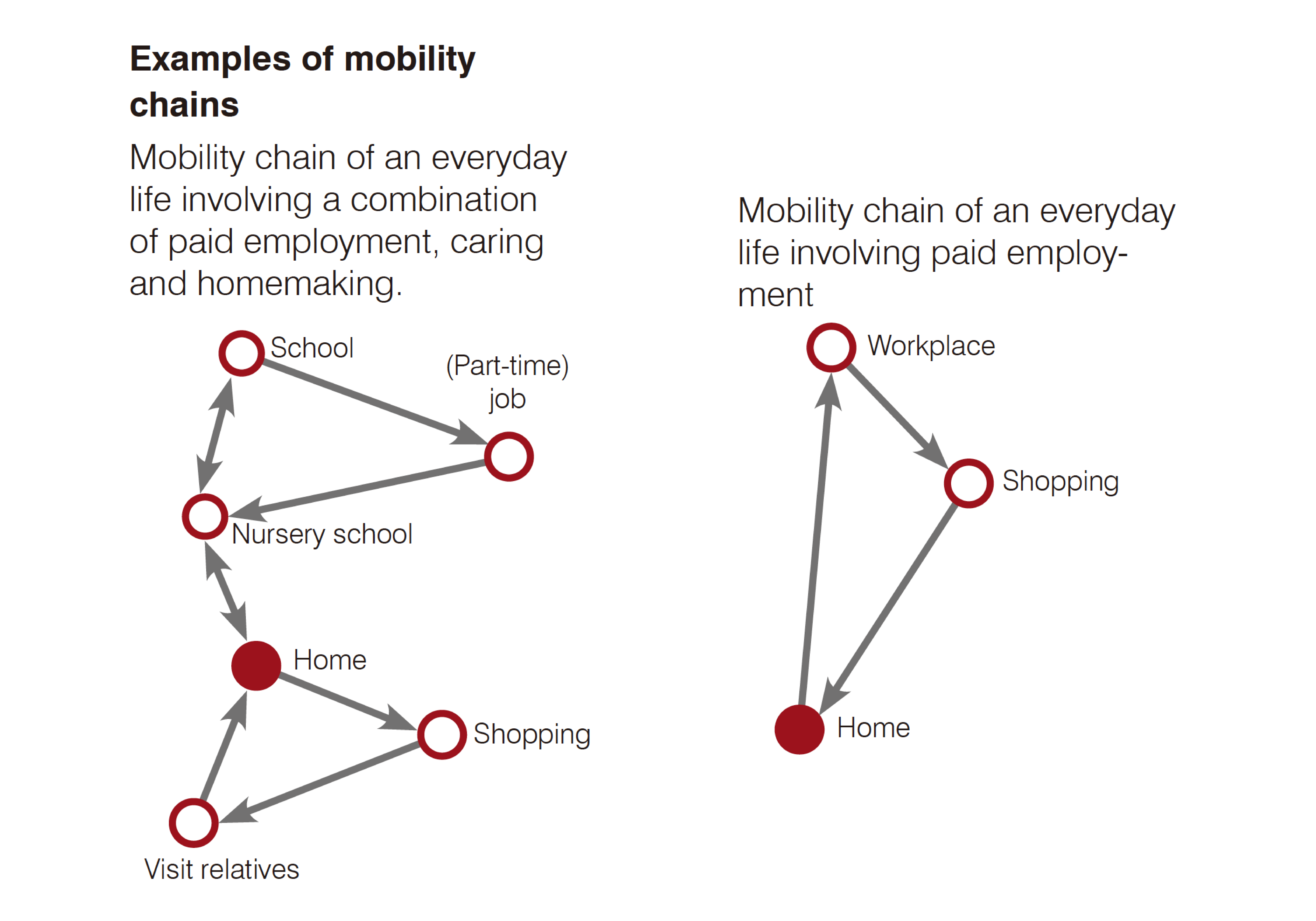

This blog is an in-depth discussion of the importance of gender mainstreaming in urban design and its practical applications. The concept of gender mainstreaming is clearly explained at the beginning of the article, and the impact of gender on urban planning and design is vividly demonstrated by comparing the different contexts in which men and women travel in the city. It points out the complexities and challenges faced by women in urban travel due to the different gender division of labour and family responsibilities, thus highlighting the necessity of gender mainstreaming in urban design, and the article clarifies the goals of gender mainstreaming, including increasing the inclusiveness of public spaces, promoting social connections, ensuring the representation of marginalised groups, and reducing the fear of harassment, all of which are important to promote a more equitable and inclusive urban Directions.

Secondly, blog takes Vienna as an example to detail the practice of gender mainstreaming in urban design. By showing specific projects and implementation measures, the article gives readers a more intuitive understanding of the implementation of gender mainstreaming. Pictures are used to illustrate the concept and practice of gender mainstreaming, making the content more vivid and easy to understand.

Thirdly, although blog has provided a more comprehensive introduction to the concept and practice of gender mainstreaming, it could be further deepened to explore how to better integrate gender factors in practice, and the applicability and challenges of gender mainstreaming in different cultural and geographical contexts. The images in the article are a good aid in explaining the concept and practice of gender mainstreaming. To further enhance the readability of the article, short textual captions can be added alongside the images to help readers better understand their content. In addition, more intuitive graphical methods such as flowcharts and schematic diagrams can be considered to show the exact process and effects of gender mainstreaming in urban design.

Overall, this is an excellent article on the application of gender mainstreaming in urban design, which not only provides clear conceptual explanations and concrete case studies, but also highlights the importance of gender mainstreaming in promoting equity and inclusion in cities.

References:

1.^ “What is Urban Design?”. Urban Design Group. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

2.^ Rosenzweig, Cynthia; Solecki, William D.; Romero-Lankao, Patricia; Mehrotra, Shagun; Dhakal, Shobhakar; Ibrahim, Somayya Ali (29 March 2018). Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-94456-1. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

3.^ Wheeler, Stephen M. (18 July 2013). Planning for Sustainability: Creating Livable, Equitable and Ecological Communities. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-48201-4.

4.^ Jump up to: a b c Padmanaban, Deepa (9 June 2022). “How cities can fight climate change”. Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-060922-1. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

5.^ Van Assche, K.; Beunen, R.; Duineveld, M.; de Jong, H. (2013). “Co-evolutions of planning and design: Risks and benefits of design perspectives in planning systems”. Planning Theory. 12(2): 177–98. doi:10.1177/1473095212456771. S2CID 109970261. Archived from the original on 2013-06-28. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

6.^ Moudon, Anne Vernez (1992). “A Catholic Approach to Organizing What Urban Designers Should Know”. Journal of Planning Literature. 6 (4): 331–349.

This is a very brilliant and detailed blog. Gender mainstreaming is a concept that involves integrating a gender perspective into all policies, programs, and actions, with the aim of promoting gender equality. It seeks to ensure that the different needs, realities, and experiences of women, men, and gender-diverse individuals are considered and addressed in decision-making processes and resource allocation.

The scenarios author described illustrate how gender roles can shape individuals’ experiences of urban spaces. For instance, the example of the mother navigating a metro station with a stroller highlights the challenges women may face due to caregiving responsibilities, such as accessing public transportation and managing multiple travel routes. The examples from Vienna and Brussels demonstrate practical applications of gender mainstreaming in urban planning. In Vienna, pilot projects focused on addressing gender-specific aspects of urban design, such as sidewalk widening and improved lighting. In Brussels, initiatives like “Girls Make the City” aimed to make public spaces like skate parks more inviting and inclusive for girls and women.

The article provides some examples, such as practices in Vienna and Brussels, but lacks in-depth data support on the impact and effectiveness of gender mainstream. More research and data analysis can enhance the persuasiveness of the article and more clearly demonstrate the actual impact of gender mainstream in urban design.

References

[1] Julie (2023) Girls make the city (Eng), zijkant. Available at: https://www.zijkant.be/girls-make-the-city-eng/ (Accessed: 16 March 2024).

[2] Her city – a guide for cities to sustainable and Inclusive Urban Planning and design together with girls (third edition) (no date) UN. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/her-city-a-guide-for-cities-to-sustainable-and-inclusive-urban-planning-and-design-together-with (Accessed: 16 March 2024).

Greed, C. (2017) discusses how considering women’s daily needs can enhance the effectiveness of urban planning. Her research suggests that Greed, C. (2017) discusses how considering women’s daily needs can improve the effectiveness of urban planning. Her research shows that gender-sensitive design not only improves women’s urban experience, but also enhances the overall functionality and sustainability of cities. This blog demonstrates this point well, effectively emphasising the importance of integrating gender into urban planning.Pojani, D. (2023) highlights that urban design often ignores the needs of female users, particularly in the design of public transport systems. Many examples are provided in this blog, such as women’s caring responsibilities requiring them to go through more complex travel chains, and improved public facilities in Vienna to support pram and wheelchair users demonstrating the adaptability of physical space to gendered needs. Meanwhile, the Girls Make the City project in Brussels emphasises community engagement and group-specific design strategies.

The blog also mentions Dorina Pojani’s research, which highlights the need to consider women’s needs in urban design. These practical examples and academic perspectives provide a holistic perspective for understanding and promoting the implementation of gender mainstreaming in urban planning.

In conclusion, this blog effectively communicates the importance of gender-sensitive urban design in enhancing the inclusiveness, safety and accessibility of cities through a combination of theory and practice. This shows that gender mainstreaming is not only a theoretical concept, but also a key to systematically improving the status quo of gender inequality in urban planning and design.

References

Pojani, D. (2023) ‘The challenge for chauffeur mums: navigating a city that wasn’t planned for women’, The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/the-challenge-for-chauffeur-mums-navigating-a-city-that-wasnt-planned-for-women-193392 (Accessed: 16 March 2024).

Greed, C. (2017) Urban Planning and Gender Inequality. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

This blog post provides an in-depth look at the application of gender mainstreaming in urban planning, and particular emphasis on the differences in needs of different genders in daily travel and space use. Through concrete examples, such as projects in Vienna and Brussels, the article shows how gender-sensitive design can improve the inclusivity and accessibility of urban spaces.

While the practice of gender mainstreaming in urban planning has been successful in raising awareness of women’s needs, we should not ignore the broader issue of gender inclusivity. Most current strategies focus on traditional male and female gender roles and ignore the specific needs of transgender, non-binary and other groups. For example, the challenges and barriers these groups may face should be considered more deeply in the design of urban transportation and public spaces[1].

In addition, the practice of gender mainstreaming also requires reflection on whether it has truly achieved the desired social effects. Although providing wider sidewalks and better lighting is progress, true gender equality will also require profound changes in social structures and cultural perceptions. For example, in addition to the transformation of physical spaces, urban planners should also promote gender equality awareness through policy support and public education[2].

Therefore, we should pursue a more comprehensive gender mainstreaming strategy that not only considers women’s safety in design, but also broadly reshapes our understanding of gender and the way we use urban space to build a truly inclusive and equal urban environment.

References:

[1]UN Habitat. (no date) Her city – a guide for cities to sustainable and Inclusive Urban Planning and design together with girls (third edition). Available at: https://unhabitat.org/her-city-a-guide-for-cities-to-sustainable-and-inclusive-urban-planning-and-design-together-with (Accessed: 16 March 2024).

[2]WomenMobilizeWomen. (2023) Gender mainstreaming in urban planning and Urban Development. Available at: https://womenmobilize.org/pubs/gender-mainstreaming-in-urban-planning-and-urban-development/ (Accessed: 16 March 2024).