What makes a good neighbourhood?

When you ask the question “what makes a good neighbourhood” what comes to mind? A sense of belonging, a sense of community, a sense of place? A place with facilities for work, leisure and play? Effective links and connections to other places? The criteria we use to judge a good neighbourhood are subjective and, as cities are dynamic environments, these criteria may change over time. One may perceive a neighbourhood to improve over time or go into decline. Another may perceive it differently.

Urban designers aim to understand these criteria and to use design to influence positive change in cities. Perhaps the most influential neighbourhood design has been Clarence Perry’s neighbourhood unit, developed in the USA in the 1920s, which defines the four basic elements a good neighbourhood unit should contain:

• An elementary school

• Small parks and playgrounds

• Small stores

• A configuration that allows all public facilities to be within safe pedestrian access.

Clarence Perry’s neighbourhood unit from Perry, C. The Neighbourhood Unit (1929)

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:New_York_Regional_Survey,_Vol_7.jpg

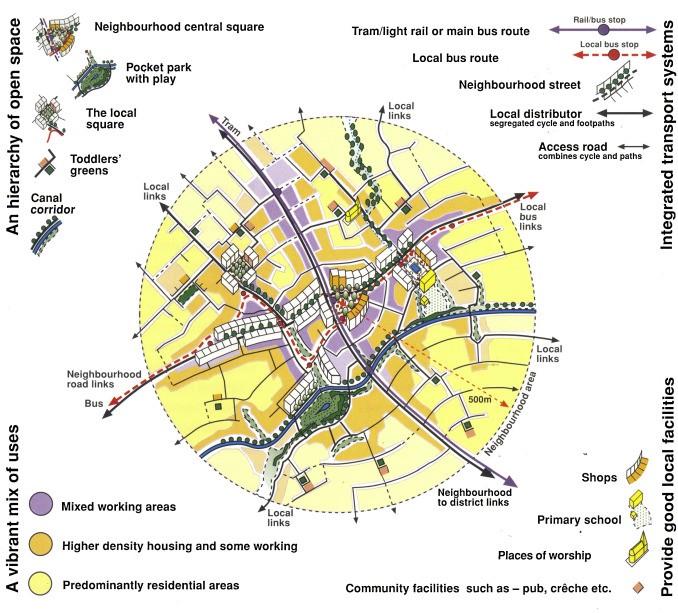

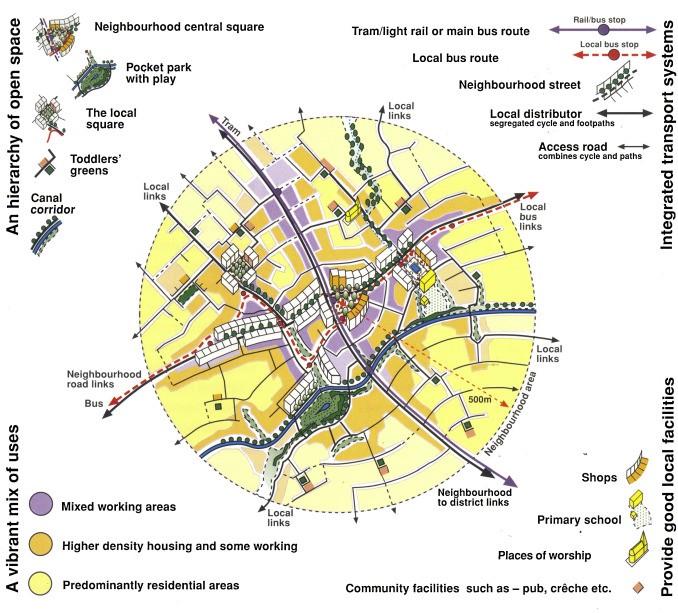

Perry’s ideas were adopted as a means of organising and developing parts of cities in a logical and systematic fashion, and they have influenced many neighbourhood designs throughout the last century, for example the New Urbanism movement in the USA (Duany et al.2000) and the Urban Villages movement in the UK (Aldous 1992; Biddulph 2000).

Neighbourhoods are, however, more complex than being simply a physical arrangement of buildings, streets and open spaces. There are also social elements of neighbourhoods such as neighbourhood interaction, and the creation of identity and a sense of community. Effective neighbourhood design should consider both physical and social elements, and it should aim to contribute to something larger, so that the “whole” is greater than the sum of its parts.

The idea of mixed-use neighbourhood design aims to blend physical and social elements to create socially balanced communities. They are neighbourhoods which provide a diversity of building forms and scales, mixed tenures and facilities and activities close to homes. Mixed use designs are supported by sustainable, environmentally friendly transport infrastructure. Krier (1990) suggests cities should be conceived of as a “family” of quarters, with each quarter being a “city within a city”. He suggests each quarter should not exceed 35ha and 15000 inhabitants.

Mixed Used Neighbourhood from “Towards an Urban Renaissance” by Urban Task Force (1999) p.66

Image Source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Urban-Task-Force-prescription-for-pyramids-of-intensity-converging-on-mixed-use_fig28_263666636

The concept of a “walkable neighbourhood” is closely linked to a consideration of its ideal size. It is widely accepted that the preferred area is often limited to a comfortable walking distance, which is either 5-10 minutes or 300-500m, although the preferred size is sometimes derived from the catchment’s population for a primary or elementary school.

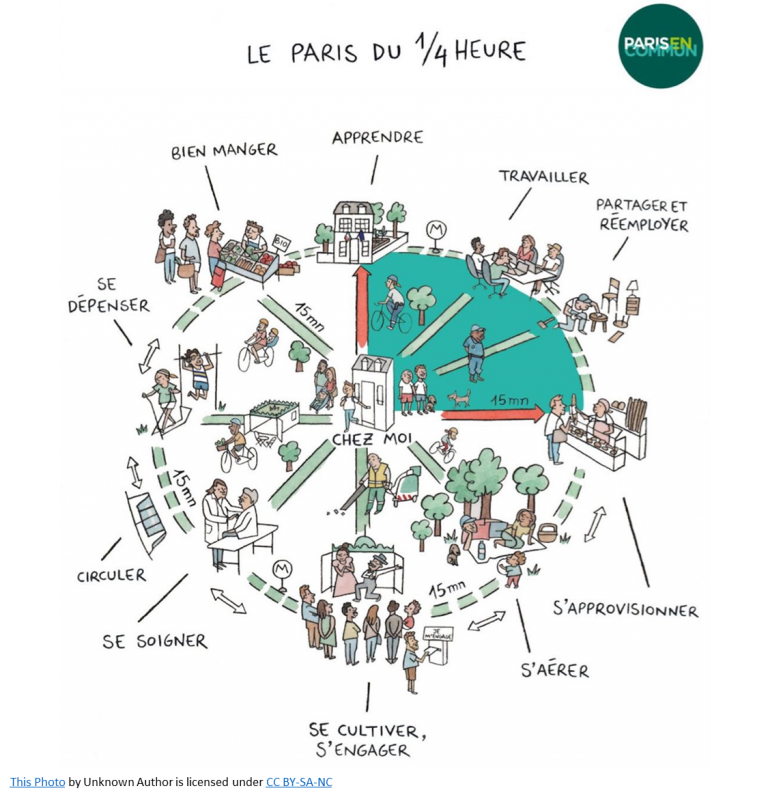

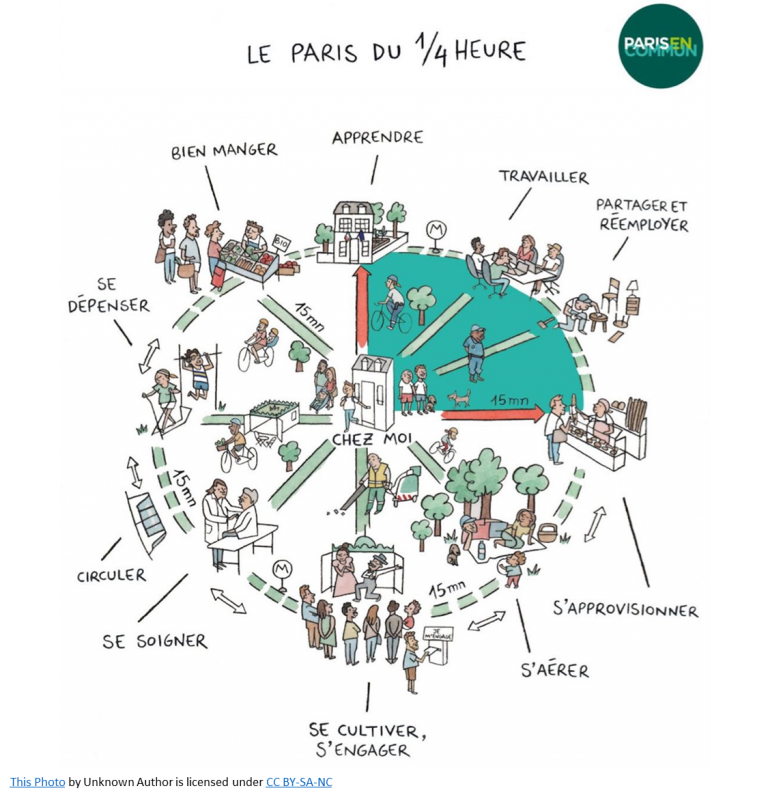

The concept has been revisited recently by the Franco-Colombian academic Carlos Moreno from the University of Paris who has developed notions of “Chronotopia” and micro-urbanism to propose the concept of the 15-minute City. He suggests that in order to reduce our environmental and climatic impact, city inhabitants should not have to travel for more than 15 minutes by foot or bicycle to access six key functions: suitable housing, learning, working and health facilities, shopping and human development places (leisure, sport and culture).

Paris en Commun’s “15-minute city” concept sketch. Clockwise from the top the headings read: Education, Work, Knowledge Exchange, Shopping, Recreation, Community Engagement, Health, Public Transport, Exercise, and Nutrition.

Image source: https://360.here.com/15-minute-cities-infrastructure

The recent Coronavirus pandemic has forced people to reassess how well designed their neighbourhoods are. Many residents were forced to work remotely and told to avoid public spaces and education institutions. They were asked to limit their journeys to those for essential purposes such as for exercise, shopping for food or medical appointments. Could the combination of adopting mixed use neighbourhood design ideas, growing concerns about climate change, and changing social behaviours help incorporate the 15-minute city philosophy into urban designs of the future?

Paris’s Mayor Anne Hidalgo certainly seems to think so; the philosophy became a cornerstone of her Mayoral campaign and in her 7 years as Mayor of Paris she has become known for her flagship environmental policies which include transforming of the banks of the Seine into promenades and banning high-polluting cars from Paris’s streets.

Newcastle City Council has now also adopted the idea in its Net Zero Newcastle- 2030 Action Plan (Newcastle City Council, 2020 p.63) which sets out how the approach could help contribute to making the city of Newcastle become Carbon Neutral by the end of the decade. In my next blog I will examine the challenges the Council may face in achieving its 15-minute city goal.

Effective neighbourhood design has evolved from Clarence’s division of space into practical chunks. Jane Jacobs’ appreciation of the humanistic elements of neighbourhood inspired the mixed-use designs which characterise developments of the 1980s and 1990s. Now the rapid urbanisation of the 21st Century, coupled with rapid technological advances and unprecedented social behaviours mean that the neighbourhood designs of the future will have to demonstrate even wider objectives. In addition to containing physical and social elements, designs must also be pliable, adaptable and environmentally sustainable.

References:

Aldous, T (1992) Urban Village: a concept for creating Mixed-use Developments on a Sustaiable Scale, Urban Villages Group, London

Biddulph, M (2000) Villages don’t make a city, Journal of Urban Design, 5 (1) 65-82

Duany, A & Plater-Zybeck, E with Speck, J (2000) Suburbn Nation: The rise and Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream, North Point press, New York

Krier, R (1990) Typological elements of the concept of urban space, Papadakis, A & Watson, H (1990) (editors)New Classicism: Omnibus Editions, London, 212-219

Moreno, C (2020) The 15 minute City https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/Carlos-Moreno-The-15-minute-city?language=en_US

Perry, C (1929) The Neighbourhood Unit, in Lewis, H.M. Regional Plan for New York and its Environs, Volume 7, Neighbourhood and Community Planning, New York

I couldn’t agree with you more. The specific vision of a good community is varied from person to person, and there is no right or wrong way to look at it. Still, for each community, convenience is indeed necessary to meet the basic daily needs of everyone in the community.

But for the community’s residents, convenience is indeed a necessity to meet their needs. It is in line with the design concept of the ‘neighbourhood unit,’ which Clarence Perry defines as a good unit containing a primary school, small park and playground, small shops, and access to all amenities. However, the concept of community is complex. A good community should meet people’s needs physically and socially. To a certain extent, this may meet the social needs of people within the community. Still, this is not conducive to community-to-community interaction in the long term as long-term living in a community unit may lead to a similar lifestyle. It can exclude some people while accommodating others who fit the profile and increase social differentiation. It reminds me of Gentrification and Social Mixing (Gentrification has long been associated with a call for diversity and difference and social mixing).

Of course, before I talk about Gentrification and Social Mixing, I must say that this policy has so far been a failure because the destruction of low-cost working-class housing to build something of high value that the middle class will buy is a violation of houses as places to dwell. I started out thinking that this policy was not practicable, but gentrification is increasingly promoted in Europe and North America policy circles. But now, I think the awareness of this policy is good because it works to break down the barriers of communication between different communities. It implies that we should do more to satisfy people’s requirements in communicating and diminishing social inequality in long-term and sustainable consideration.

Lees, L., 2008, Gentrification and social mixing: Towards an inclusive urban renaissance? Urban Studies 45 (12), pp. 2449-2470