‘Woonerf’: A Refuge Opportunity for Us All

‘Woonerf’: A Refuge Opportunity for Us All

“The modern street in the true sense of the word is a new type of organism, a sort of stretched out workshop, a home for many complex and delicate organs, such as gas, water and electric mains.” (Le Corbusier, 1929)

However, our streets are more than just Le Corbusier’s depiction of them as a masterpiece of civil engineering. These spaces facilitate growth, play and exercise. They enable both formal and informal modes of human interaction. They provide the very foundations on which us homo sapiens live and evolve. It is the tangible and the intangible, the conscious and the subconscious that contribute to the fundamentality of these ‘organisms’ to human existence. Yet, this ideology of the street has become a utopian construct, a sort of fictional fairytale. Today, we are surrounded by machine dominated, crime infested battlegrounds where the concept of ‘community’ is often neglected.

Daytime. Mania ensues as streets are littered with metal carcasses in a desperate effort to avoid any kind of physical activity. Fossil fuelled tyrants blast past in a CO2 emitting, noise polluting frenzy. Cumbersome, unwieldy trucks trawl from door to door delivering the best that the internet has to offer with the click of a button. With more cars than English households, we have lost our streets to a de-humanised, machine oriented way of life (Yurday, 2021).

Nighttime. As darkness falls, the DNA of our streets change and they become home to the criminal underworld. Doors get locked and blinds get shut in our futile attempts to fortify ourselves from the barbarism. Alleyways and blind spots comprise no-mans-land, where only the bravest of people dare to venture. The street is now a territorial war-zone flanked by thugs, drugs and illegality. This is the reality of today and with nearly half of the UK population feeling no sense of community where they live, something must change (Diaconu, 2020).

‘Woonerf’

A major factor contributing to the deterioration of street function and use is the organisation of the infrastructure, spaces and buildings that compose them. It is the legacy of semi-corbusian design. In Holland, 1963, this began to change. Originally, recognition of considered and current Urban Design as a prerequisite for street harmony was seen in the Buchanan Report (1963). This highlighted ‘the conflict between providing for easy traffic flow and the destruction of the residential and architectural fabric of the street.’ What followed was an astute attempt to rectify these issues. Delft, Holland (1969) became the first ‘Woonerf’ or home-zone (see figure 1), (Department for Transport, 2005). The UK then adopted this strategy in the turn of the millennia.

Figure 1: Image of the first ‘Woonerf’ in Delft, Holland.

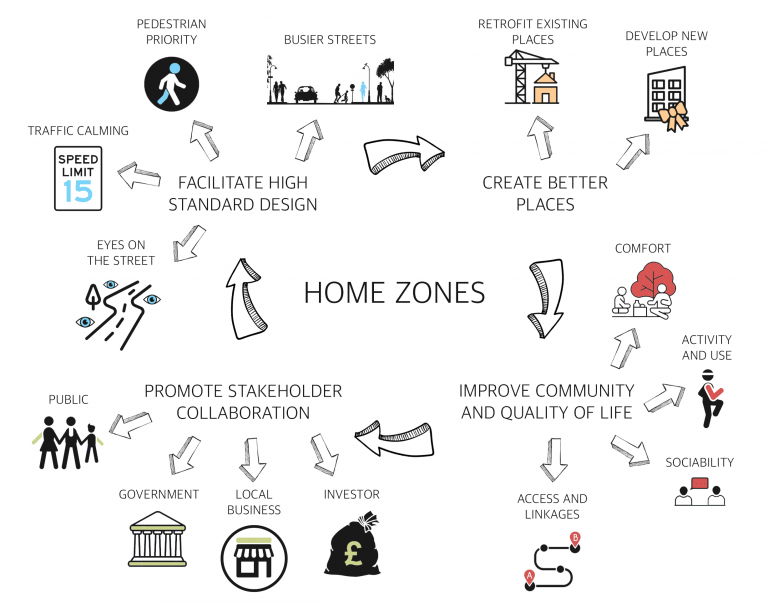

Due to the nature of the home-zone ideology, an attempt to define it would be illogical. There is no blueprint. Each scheme should reflect the aspirations of its individual locality. Nevertheless, there are some characteristics used and recognised internationally that fulfil similar objectives (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Home-zone concept diagram.

What Makes a Home-zone?

One common aim throughout many home-zone projects is to make streets a space where humans take precedence over vehicles. Though it might seem obvious, this adjustment of street hierarchy can significantly improve quality of life. It creates a space where kids can play and learn, and neighbourly interaction is a usual occurrence. Ultimately, a type of residential sanctuary can be formed fostering a prosperous, community led environment. So how is this achieved?

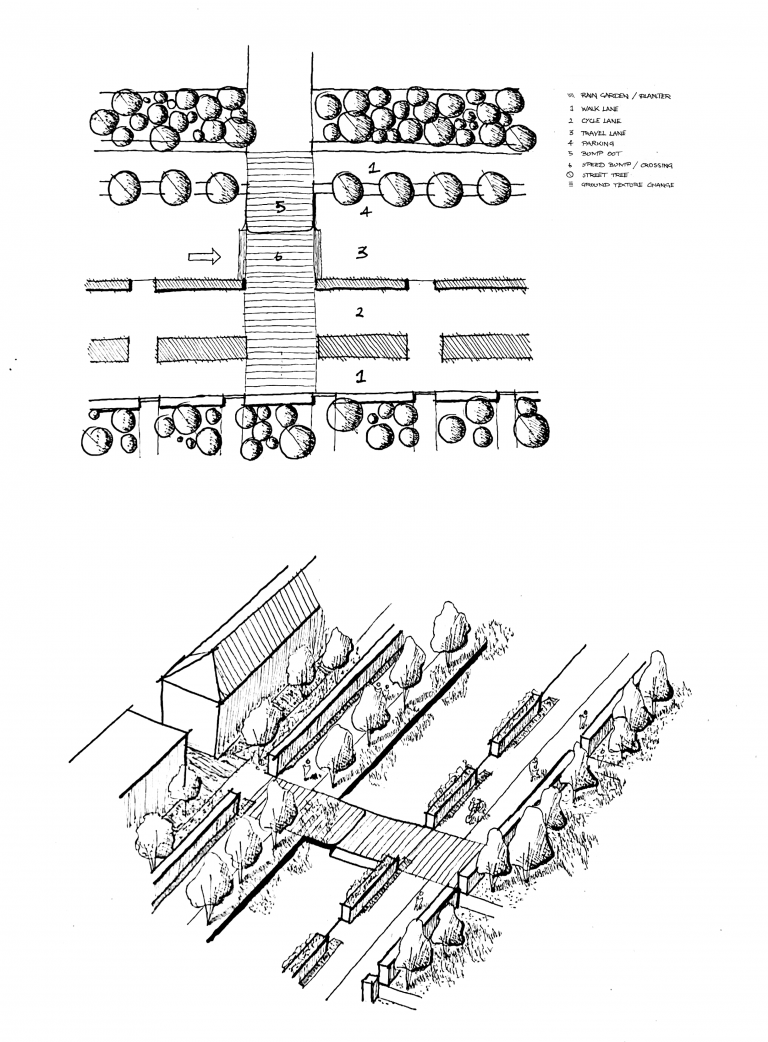

First of all, the implementation of traffic calming measures is crucial. This means reducing speed limits below 20mph, constructing speed bumps and reducing the travel lanes down to a single carriageway (Institute of Highway Incorporated Engineers, 2002). The result is a reduction of drivers using an area as a thoroughfare and increased pedestrian safety. Other measures that can be taken are the widening of pavements, provision of public space and integrated flourishes of green infrastructure within the streetscape (see figure 3). The outcome is a more habitable habitat for its inhabitants.

Figure 3: Section showing an idealistic home-zoned street.

Busier streets is an idea that is supported by author Jane Jacobs. Jacobs (1961) insists that a streets peace ‘is kept primarily by an intricate, almost unconscious network of voluntary controls and standards among the people themselves’. Additionally, Jacobs posits that ‘eyes on the street’ can significantly reduce crime rates. This is where windowed facades and balconies add to the ‘network of voluntary controls’. It is a design that mitigates the blindspots and alleyways comprising no-mans-land. Thus, the role of the Urban Designer is pivotal here.

Nonetheless, home-zones don’t only free us from the chaos of cars and crime, they are an extension of peoples homes. Residents can escape from the trial and tribulation of life that we all encounter on a daily basis. They are a refuge opportunity for us all (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Plan and Axonometric of a home-zone residential street.

Figure 4: Plan and Axonometric of a home-zone residential street.

Therefore, a re-structured street hierarchy and access to higher quality public space are the stepping stones to ‘organisms’ with the potential to make our utopian, fairytale-esque ideologies of the street a reality.

List of Figures

Figure 1: Image of the first ‘Woonerf’ in Holland.

Figure 2: Home-zone concept diagram.

Figure 3: Section showing an idealistic home-zoned street.

Figure 4: Plan and Section of a home-zone residential street.

References

Department for Transport (2005) Homezones: Challenging the Future of our Streets. [Accessed 25th November 2021] Available from: https://nacto.org/docs/usdg/home_zones_department_transpot.pdf

Diaconu, C. (2020) UK’s decline in sense of community. [Accessed 25th November 2021]. Available from:

Gill, T. (2006). Home Zones in the UK: History, Policy and Impact on Children and Youth. Children, Youth and Environments, 16(1), 90–103. [Accessed 25th November 2021]. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.16.1.0090

Institute of Highway Incorporated Engineers. (2002) Homezone: Design Guidelines. [Accessed 25th November 2021]. Available from: https://www.theihe.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Home-Zone-Design-Guideline.pdf

Jacobs, J. (1961) The Uses of Sidewalks: Safety. In The City Reader. [Accessed 27th November 2021]. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=hAItCgAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&ots=OP

Le Corbusier (1929) A Contemporary City. In The City Reader. [Accessed 25th November 2021]. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=hAItCgAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&ots=OP

Park, L, S. (2004). [Review of Home Zones: A Planning and Design Handbook, by Biddulph, Mike]. Children, Youth and Environments, 14(1), 284–287. [Accessed 25th November 2021]. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.14.1.0284

Yurday, E. (2021) Number of Cars in the UK 2022. [Accessed 27th November 2021]. Available from: https://www.nimblefins.co.uk/cheap-car-insurance/number-cars-great-britain