________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

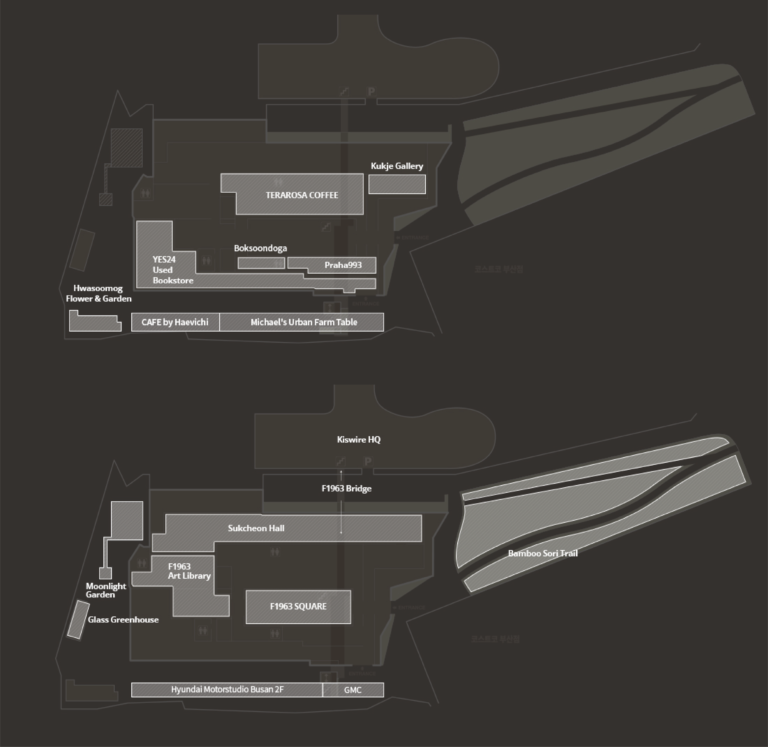

I would first like to commend you for providing clear key points to quickly inform the reader of the lecture’s premise. I also found the ‘F1963’ precedent to be a fitting example of an industrial renovation project, greatly relevant to the first portion of the lecture. A couple of quick observations: I think it would have been beneficial to quickly outline and summarize the portion of the lecture pertaining to Misery Quarry and found ways to relate your precedent (F1963) back to how it could be implemented in the desolate, abandoned quarry; or further explained its connection to Île de Nantes. For example, I find the factory’s programming (exhibition, restaurant, library, etc.) to be a very intriguing feature that may be a starting point to involving local citizens in the designing of Misery Quarry.

While reading this post, I had a couple references/precedents come to mind. Naturally, one of these precedents resides in my hometown of Toronto, Canada: 401 Richmond. Originally a canning factory, 401 Richmond has since been redeveloped into the iconic arts hub it is known as today. Guided by the vision of Margie Ziedler, the warehouse was reimagined in 1994 as a “Village in a Box” (Way, 2013). During the time when the industrial building was purchased, “the surrounding neighborhood from which the Queen Street West art scene had emerged was characterized as ‘totally dead’ and the building as ‘largely vacant’”(Bain & Marsh, 2019, p. 184). Ziedler turned to the principles of Jane Jacobs to embrace what appear as desolate spaces and structures to provide the local and greater community with raw studio spaces. Today, 401 Richmond holds 140 tenants with 79% of them being art-based – social and creative innovation fields (Bain & Marsh, 2019, p. 186). Reverting to the post, 401 Richmond takes on a similar approach as F1963, injecting ‘cultural’ spaces into a nostalgic yet purposeless industrial building. I feel that providing a space for the creative community to congregate can be a method to involve locals and create the sense of a ’place.’

The second reference that came to mind is an article I read recently titled: “Landscapes of industrial excess: A thick sections approach to Gas Works Park,” written by Thäisa Way. In summation, Way brings to light the revolutionary regeneration of Gas Works Park in Seattle, Washington done by Richard Haag Associates. Haag’s design decisions are what led to the park being, “the first post-industrial landscape to be transformed into public space without requiring the removal of its pollutants and waste to a landfill” (Way, 2013, p. 8). Furthermore, instead of removing the rusted industrial apparatuses on the site, Haag left them as what became iconic public art (Way, 2013). In turn, the article got me thinking about different means of reusing industrial buildings and the corresponding sites. Can these industrial pieces become informative reminders of the past?

In conclusion, what I have drawn from the post and these various references/precedents is the urgent need to find more innovative reuses of obsolete structures, especially solutions that don’t follow the process of demolition and rebuilding. An answer to this appears to be found in local participation in the design process.

_____________

References

Bain, A. L., & March, L. (2019). Urban Redevelopment, Cultural Philanthropy and the Commodification of

Artistic Authenticity in Toronto. City & Community, 18(1), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12359

Way, T. (2013). Landscapes of industrial excess: A thick sections approach to Gas Works Park. Journal of

Landscape Architecture, 8(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2013.798920

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I would first like to commend you for providing clear key points to quickly inform the reader of the lecture’s premise. I also found the ‘F1963’ precedent to be a fitting example of an industrial renovation project, greatly relevant to the first portion of the lecture. A couple of quick observations: I think it would have been beneficial to quickly outline and summarize the portion of the lecture pertaining to Misery Quarry and found ways to relate your precedent (F1963) back to how it could be implemented in the desolate, abandoned quarry; or further explained its connection to Île de Nantes. For example, I find the factory’s programming (exhibition, restaurant, library, etc.) to be a very intriguing feature that may be a starting point to involving local citizens in the designing of Misery Quarry.

While reading this post, I had a couple references/precedents come to mind. Naturally, one of these precedents resides in my hometown of Toronto, Canada: 401 Richmond. Originally a canning factory, 401 Richmond has since been redeveloped into the iconic arts hub it is known as today. Guided by the vision of Margie Ziedler, the warehouse was reimagined in 1994 as a “Village in a Box” (Way, 2013). During the time when the industrial building was purchased, “the surrounding neighborhood from which the Queen Street West art scene had emerged was characterized as ‘totally dead’ and the building as ‘largely vacant’”(Bain & Marsh, 2019, p. 184). Ziedler turned to the principles of Jane Jacobs to embrace what appear as desolate spaces and structures to provide the local and greater community with raw studio spaces. Today, 401 Richmond holds 140 tenants with 79% of them being art-based – social and creative innovation fields (Bain & Marsh, 2019, p. 186). Reverting to the post, 401 Richmond takes on a similar approach as F1963, injecting ‘cultural’ spaces into a nostalgic yet purposeless industrial building. I feel that providing a space for the creative community to congregate can be a method to involve locals and create the sense of a ’place.’

The second reference that came to mind is an article I read recently titled: “Landscapes of industrial excess: A thick sections approach to Gas Works Park,” written by Thäisa Way. In summation, Way brings to light the revolutionary regeneration of Gas Works Park in Seattle, Washington done by Richard Haag Associates. Haag’s design decisions are what led to the park being, “the first post-industrial landscape to be transformed into public space without requiring the removal of its pollutants and waste to a landfill” (Way, 2013, p. 8). Furthermore, instead of removing the rusted industrial apparatuses on the site, Haag left them as what became iconic public art (Way, 2013). In turn, the article got me thinking about different means of reusing industrial buildings and the corresponding sites. Can these industrial pieces become informative reminders of the past?

In conclusion, what I have drawn from the post and these various references/precedents is the urgent need to find more innovative reuses of obsolete structures, especially solutions that don’t follow the process of demolition and rebuilding. An answer to this appears to be found in local participation in the design process.

_____________

References

Bain, A. L., & March, L. (2019). Urban Redevelopment, Cultural Philanthropy and the Commodification of

Artistic Authenticity in Toronto. City & Community, 18(1), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12359

Way, T. (2013). Landscapes of industrial excess: A thick sections approach to Gas Works Park. Journal of

Landscape Architecture, 8(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2013.798920

Firstly, I’d like to congratulate you on your post. The F1963 project is a very good example of adaptive reuse of historical industrial buildings and it is exciting to see through images the site’s transformation from the Suyeong factory which was the first plant that became the basis of Korea Steel to what is now an art gallery.

However, the post does not discuss any form of public involvement in its development which is a key theme of your post, unlike the Île de Nantes urban project you have mentioned. There are five different stages of civic participation that include information, consultation, involvement, collaboration and empowerment. (UN Habitat 2014). The site for the Île de Nantes urban project was a previous dockyard area that closed in the 1980s (Morteau 2020). A run through of the Île des machines (mechanical creatures designed as part of the wider Île de Nantes urban project) was carried out by citizens during their development to understand the citizens’ needs (Morteau 2020). This type of community participation involves consultation where society is given an insight into future projects affecting their neighbourhood without the opportunity to fully participate in decision making. This is often done, for instance, through workshops, surveys, etc. Residents may share opinions but these are not necessarily put to use in project design (UN Habitat 2014).

Another really good example of community engagement in city design is the Seattle Gas works Park in Washington. The site was a former gas works site that produced gas from coal and oil in 1906 and later closed in 1956. In 1962, Richard Hagg was commissioned to rehabilitate the site seen by the residents as a reminder of the disregard for nature (Way 2013). However, Hagg convinced citizens to look at the old machinery using a new lens. He dwelled on the fact that his idea centred around the creation a picturesque environment even though it included retaining the site’s archaic equipment (Way 2013). This form of participation is termed involvement where residents are given room to contribute to decisions on neighbourhood projects without a guarantee that they will be followed. This is often through negotiation in public discussions and physical meetings. (UN Habitat 2014).

Therefore, the different stages of community involvement in urban/city design help us understand the degree of influence society has in the design of neighbourhoods. It is important to note that achieving maximum participation that wholly meets citizens’ needs requires engaging them at the beginning of projects. (UN Habitat 2014). It would add a lot of value understanding the contribution of community participation to the regeneration of project Île de Nantes.

References

Helene Morteau (2020), Nantes: from a creative to an experimental city. Urban Maestro

UN Habitat (2014), Guidelines for Public participation in Spatial Planning : Municipal Spatial Planning Support Programme in Kosovo. Swedish Development Cooperation

Way Thaisa (2013), Landscapes of industrial excess: A thick sections approach to Gas Works Park. University of Washington, Seattle, USA